Thoughts and Reflections on the Tennessee Williams Archives

Alive, Tennessee Williams was one of the most prolific writers of his day; dead now forty years, he continues to be so. Why and how is a story as simple and as complex as the playwright was himself.

The simple version of the story is that T. Williams wrote almost daily for over forty years, leaving behind him a trove of manuscripts at various stages of completion. Even before his death in 1983, many of these manuscripts had been scattered across the US and reside today in several archives and private collections. Scholars have been busy unearthing, collating, and editing these previously unpublished works almost yearly since the 1995 death of his self-appointed literary executor, Maria St Just, whose notorious megalomania and iron-fisted control over T. Williams’s copyrights threatened the playwright’s status for over a decade. M. St Just feared that the visibility of T. Williams’s early or late work would tarnish his great plays and contribute to his removal from the nation’s literary pantheon (and, by extension, her affiliation with his name). The opposite, in fact, occurred: the posthumous publication of many of his works sparked a renaissance in Williams studies that has confirmed his standing as America’s preeminent playwright.

The complex version of this story involves what actually gets published – and when. Publishing an author’s youthful writings over his later work is often a politically motivated decision: it is easier to maintain a writer’s reputation – and marketability – after his death with early material that informs us of a later genius rather than with work that could call that same genius into question. Such was the case with the posthumous T. Williams’s titles. Among the twenty-one full-length and thirty-three one-act plays that T. Williams published during his lifetime, his publisher New Directions and his Estate at the University of the South in Sewanee have added to the Williams canon (to date) thirteen full-length and forty-five one-act plays (not to mention additional stories and poems), the majority coming from his college years or just after: Not about Nightingales (1938; Williams [ed. Hale], 1998), Spring Storm (1937; Williams [ed. Isaac], 1999), Stairs to the Roof (1942; Williams [ed. Hale], 2000a), Fugitive Kind (1937; Williams [ed. Hale], 2001), Collected Poems (1925–81; Williams [ed. Moschovakis & Roessel], 2002), ‘In Spain There Was Revolution’ (1936; Williams [ed. Moschovakis & Roessel], 2003), Candles to the Sun (1937; Williams [ed. Isaac], 2004a), Mister Paradise and Other One-Act Plays (1935–62; Williams [ed. Moschovakis & Roessel], 2005), ‘American Gothic’ (1937; Bak, 2009), The Magic Tower and Other One-Act Plays (1936–73; Williams [ed. Keith], 2011), Now the Cats with Jeweled Claws and Other One-Act Plays (1939–82; Williams [ed. Keith], 2016a), and ‘The Taj Mahal with Ink-Wells’ (1945; Williams [ed. Bak], 2016b).

Though with much less frequency, New Directions and the estate have also been publishing the later T. Williams, confident now, as T. Williams was when he was still alive, of their literary merit and theatrical quality. Each new play or collection of late one-act plays has delivered to Williams scholars and fans alike pertinent works that have never before been seen onstage or that T. Williams’s prior readers and audiences did not fully appreciate in their day. Something Cloudy, Something Clear (1995), The Traveling Companion and Other Plays (1960–80; Williams [ed. Saddik], 2008b), and A House Not Meant to Stand (1982; Keith, 2008a) have thus demonstrated that T. Williams was not washed up at fifty but a writer in full artistic chrysalis.

Of course, most writers bequeath incomplete or mediocre works for posterity, and estates, literary executors, and scholars are faced with the dilemma of whether or not to publish that material posthumously. While it is true that, in T. Williams’s case, all of these recently published works lack the literary punch of A Streetcar Named Desire or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the more important point is that they were never meant to compete with the classics. By the early sixties, T. Williams was through writing his ‘symphonies’, as he called his major plays and, with his reputation seemingly intact, turned his attention to his ‘chamber music’, those shorter, more experimental plays like Slapstick Tragedy (Rader, 1985, p. 257). But T. Williams miscalculated the response of America’s leading theatre critics, who still judged the playwright by his last Broadway triumph (Bak, 2014, pp. 221–22). As T. Williams continued writing plays further removed from his signature style of the successful forties and fifties, his reputation suffered proportionally. With criticism often lagging behind the art it evaluates, the publication of many of his late works has been justified by the fact that several once deemed a failure in their day have garnered critical acclaim (such as The Mutilated and Something Cloudy, Something Clear), and a few are even being declared minor masterpieces (e.g. Green Eyes). With over half of his oeuvre having now appeared after his death, T. Williams is clearly enjoying a fertile literary afterlife.

While T. Williams’s fiction has enjoyed a second life, a good portion of his nonfiction regretfully remains buried in the archives. The result has been a palpable – and paradoxical – gap between T. Williams’s art and his life. Strangely, the more we know about T. Williams the playwright via these recent publications, the less we really know about T. Williams the man who wrote them, in particular the T. Williams of the later years. While T. Williams himself was frequently the source of this misinformation (from the exaggerated truths in his Memoirs to the questionable facticity of his later interviews), other culprits can also be implicated: the several memoirs published by friends, acolytes and wannabes who knew T. Williams well later in life (or at least claimed to) that often produced apocryphal or unsubstantiated narratives about T. Williams’s later years (Rader, 1985; Rasky, 1986; Grissom, 2015). Even Donald Spoto’s early biography (1986) entrenched these narratives more than it set the record straight – something later biographers have belaboured to do (Bak, 2013; Lahr, 2014). Therefore, while the biographical norm is to point to the spotty records of a writer’s early career to explain away historical uncertainties or inaccuracies in a writer’s life, in T. Williams’s case the opposite is true: too much of his later life is based on gossip, rumour and hearsay, published or otherwise, whereas the record of his early life for the most part has been accurately captured (Leverich, 1995).

Another reason why T. Williams’s mid- to late-nonfiction has received less attention – beyond the fact that Lyle Leverich died before completing volume two of his authoritative biography on T. Williams’s life from 1945 onwards, and John Lahr chose not to produce that book when he inherited the task after L. Leverich’s death – is that T. Williams’s published nonfiction covers essentially the first half of his life. New Directions and Yale University both scoured the many Williams archives to bring some of this nonfiction to print, and the critical and popular success of his Selected Letters (Williams [ed. Devlin & Tischler], 2000b; 2004b), his Notebooks (Williams [ed. Thornton], 2006b), and his New Selected Essays: Where I Live (Williams [ed. Bak], 2009)1 attests to the avid interest, academic and lay alike, in understanding the playwright behind the plays. Not surprisingly, scholars have largely turned to these nonfiction sources to help them explain or re-evaluate T. Williams’s fiction, both early and late. Yet the letters take readers only up to early 1957, and the Notebooks only expose T. Williams’s daily activities and private thoughts and fears from 1936 to 1958. The essays do cut a wider swath of his public life from 1927 to 1982, but, given their anecdotal nature, they half-reveal/half-obscure the meaning of his art and the reasons for which he produced it. As such, there is a penury of T. Williams’s published nonfiction (letters, essays, etc.) from the sixties onwards that currently limits our knowledge of the playwright to these early letters and notebooks.

Work has been ongoing to fill this gap, however. Two collections of T. Williams’s letters in addition to the two New Directions series have reproduced some of his post-1957 epistles, Five O’Clock Angel: Letters of Tennessee Williams to Maria St Just, 1948–1982 (1990) and The Luck of Friendship: The Letters of Tennessee Williams and James Laughlin (2018b). New Directions has yet to produce the long-awaited third volume of the Selected Letters, though the archives, particularly at Columbia and Harvard universities, do contain numerous letters that T. Williams wrote to lovers, friends, literary agents, publishers, and theatre professionals. During editorial work in 2006 on New Selected Essays, I also stumbled across a myriad of T. Williams’s prose writings – much of it fragmentary and undated – that was directly or indirectly related to his Memoirs. What that suggests is that T. Williams did want to produce an autobiography that was as artistic as it was genuinely forthcoming (Bak, 2010; 2011; 2013), and that many of these fragments were meant for inclusion in that definitive work or in a second memoir that he announced he was writing in the late seventies but never completed. These fragments, when edited and published, could join the nonfiction already in print and help scholars to sort out T. Williams’s later years with more confidence.

Several archives – including the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Centre (HRC) of the University of Texas, the Houghton Library Collection at Harvard University (HL), the Rare Book & Manuscript Library of Columbia University (RBML), the Williams Research Centre of the Historic New Orleans Collection (HNOC), the Special Collections Library of the University of Delaware (UDEL) and the Special Collections Library of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) – have been the sources of these early and late posthumous publications. And though each one of these archives shares similar manuscripts (at times identical, given T. Williams’s insistence on having his work mimeographed), each also possesses items that are unique to their collection of Williams papers.

But the larger question still looms: should we be publishing work that T. Williams himself did not include in his collected writings when he was alive? T. Williams clearly did not think so back in the sixties. In a letter to his brother Dakin, dated 20 July 1962, T. Williams states his fears about the efforts undertaken by Andreas Brown, owner of the famed Gotham Book Mart and T. Williams’s official bibliographer back then, to unearth his college papers at his mother’s house in St. Louis:

Of course I am very dubious about having poems I wrote at junior high school published, just as I am dubious about the advisability of ever publishing any of that awful ‘juvenilia’ that Mr. Andreas Brown has gotten together in the basement. I have written a few good things, just a few, and the rest is better forgotten. I think Mr. Brown means very well indeed. But it would be awful to suspect that, after my death, some book would come out containing all the discards of a life of writing. [Williams, 2018a]

That book did eventually come out after his death – books even, as noted above. Would any of them have made T. Williams blush were they actually published during his lifetime? Fume? Seek redress? Or, now that he is dead, turn in his grave? While answers to these questions vary depending on the parties asked, a few things do remain clear: T. Williams did blush when he imagined his mother reading several of his gay short stories that New Directions published in One Arm in 1948 and Hard Candy in 1954; he did fume when his on-again/off-again friend Donald Windham published their early correspondences in 1977; and he did seek legal redress against Tom Buckley in 1970 for his unflattering (and presumably off-the-record) portrait of T. Williams in The Atlantic magazine. His apprehension in each case, though, resulted from fears about how attacks on his person would affect the reception of his writing. His anger toward D. Windham, for instance, was more about his demeaning editorial comments about T. Williams than about his making public their letters’ explicit nature. Were T. Williams alive today, he would have been pleased with the publication of his late plays, though chagrined at the release of his juvenilia.

Be it the recovery of an early or a late T. Williams’s manuscript, the various archives have been a fertile font of new titles, each instrumental in teasing out the fabula from the fabulous of T. Williams’s life and career. And a cache of T. Williams’s manuscripts, fiction and nonfiction alike, is still waiting to be uncovered, edited, and published. But it would be near suicidal for the inexperienced scholar to simply jump into these archives willy-nilly. Significant reconnaissance work must first be undertaken. Locating these ‘lost’ manuscripts implies identifying (and dating) them first, and that is no easy task. T. Williams donated or sold the majority of his manuscripts during his lifetime, believing they would aid future scholars in understanding him and his art better than did the critics of his day. He also often helped out his ‘friends’ financially by bequeathing them manuscripts of his work (some were reportedly stolen), which they later sold when strapped for cash. For instance, he gave D. Windham a signed affidavit to authenticate the sale of his manuscripts (Williams, 1977, pp. 311–12), and Victor Campbell a ‘time capsule’ suitcase of manuscripts, letters, and memorabilia as insurance – for T. Williams, against future obscurity; for V. Campbell, against future poverty (Clark, 2016).2 Consequently, no single Williams archive contains the collective manuscripts of a specific major work, be it fiction or nonfiction. With the pieces to a given manuscript puzzle having been ‘scattered’ like so many of T. Williams’s ‘idioms’ across the country from Boston to New Orleans and from Austin to Los Angeles, archivists have not always been able to identify certain pages as coming from a larger Williams project. Many of these orphan documents have thus remained ‘lost’ in the Williams archives, waiting to be reunited with their parent manuscripts.

The aim of this essay, then, is to draw from my own archival experiences in compiling T. Williams’s fiction and nonfiction over the years to help future Williams scholars navigate their way through the several archives in the hopes that their future research will continue supplying titles to the Williams oeuvre. Simply put, there are new Williams titles out there waiting to be discovered, but each archive differs in how it identifies and catalogues its Williams papers, leaving some still not fully aware of the true contents of their collection. As such, scholars need to be well prepared before undertaking the ardent task of wading through the piles upon piles of incomplete, nonsequential and undated manuscript pages and paper scraps, which is what the collective Williams archives ultimately entails, in the hopes of discovering that diamond among the lumps of coal.

I am always surprised – and a bit dismayed – when I read in a local or national newspaper or magazine that someone has just ‘discovered’ a previously ‘lost’ or ‘forgotten’ T. Williams’s poem, story, or play. Anyone vaguely familiar with the Williams archives, be it at the HRC, the HL, the RBML or the HNOC, knows that practically none of T. Williams’s manuscripts was ever really lost or forgotten. Just buried. T. Williams wrote a lot and kept each single sheet of paper that passed through his manual Underwood or electric Smith Corona typewriter. What all that writing eventually amounted to are several mountains of manuscript pages, some a single sentence in length, others running for dozens if not hundreds of pages, most bearing T. Williams’s holograph corrections in pen or pencil. The linear feet of archival boxes speak for themselves: 31.5 (HRC), 27 (RBML), 24 (HL), over 4000 items (HNOC),3 4.6 (UDEL) and 1 (UCLA). In visual terms, a bowling lane is sixty feet to the head pin, and one linear foot of manuscripts can contain up to 1200 leaves (and, as is the case with UCLA, still have room for uncorrected galley proofs of Gilbert Maxwell’s book Tennessee Williams and Friends (Box 2, Folder 16)).4 In short, if they really wanted to, the Williams Estate at Sewanee could publish a ‘lost’ or ‘forgotten’ poem or story or play every day for several years. And that is not an exaggeration.

For a long time, the Tennessee Williams Archives at the Harry Ransom Centre of the University of Texas at Austin was the gold standard. Going through the collection today, though, can feel a lot like poring over table after table of someone’s basement jetsam at a village flea market. To find something of real value, you need a discerning eye, eternal patience, and a lot of luck. I say flea market and not antique fair intentionally, because, the truth be told, a lot of what the HRC holds did come from a basement sale, though that basement (and attic, no doubt) belonged to T. Williams’s mother, Edwina, hoarder extraordinaire. Flea markets can offer up a treasure now and again, and the same holds true for the Tennessee Williams Collection at the HRC (MS‑04535). A good story or play or even poem does occasionally emerge from its many boxes, and that gives us cause to celebrate. Caution should just be taken in deciding which text is worth publishing.

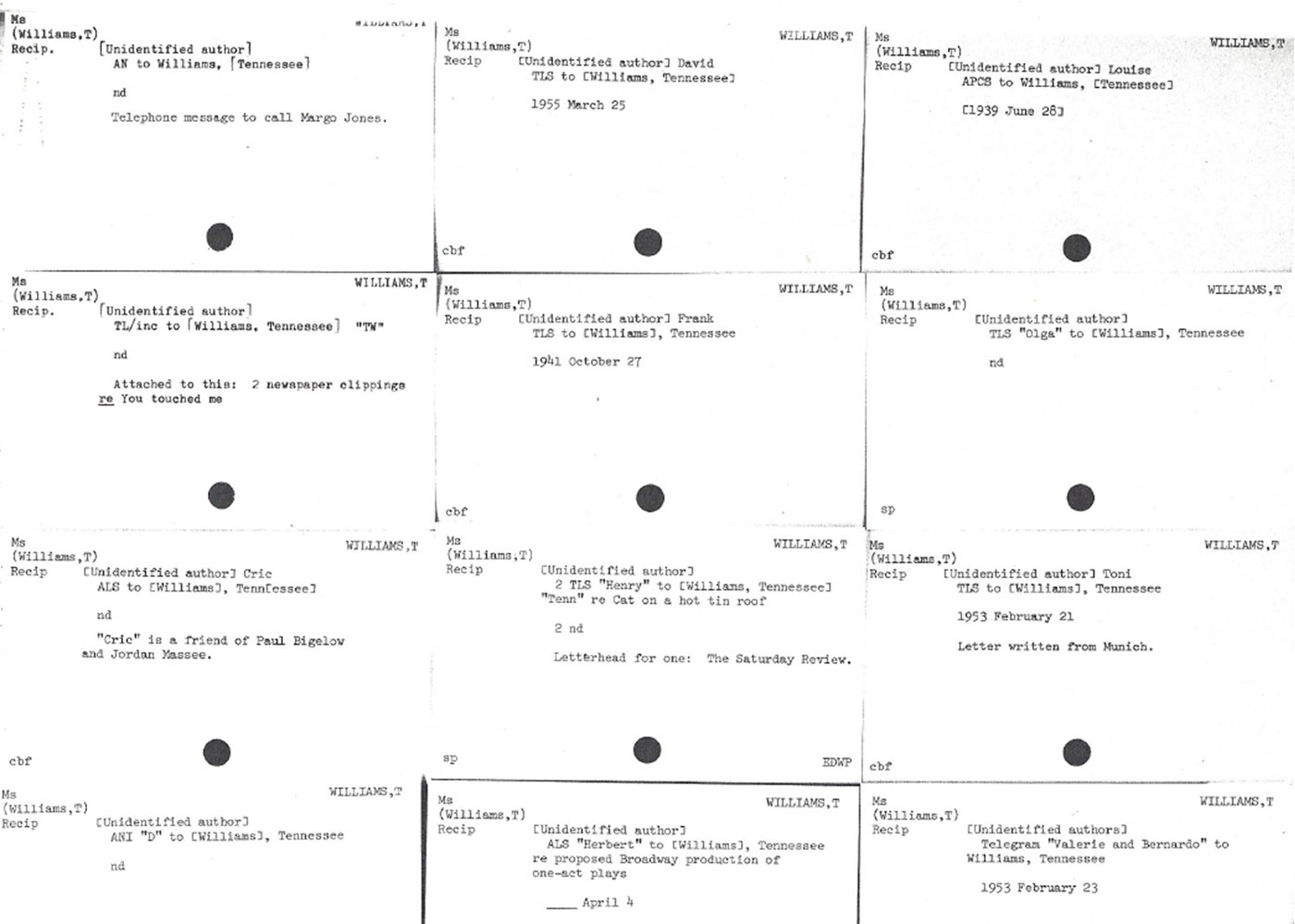

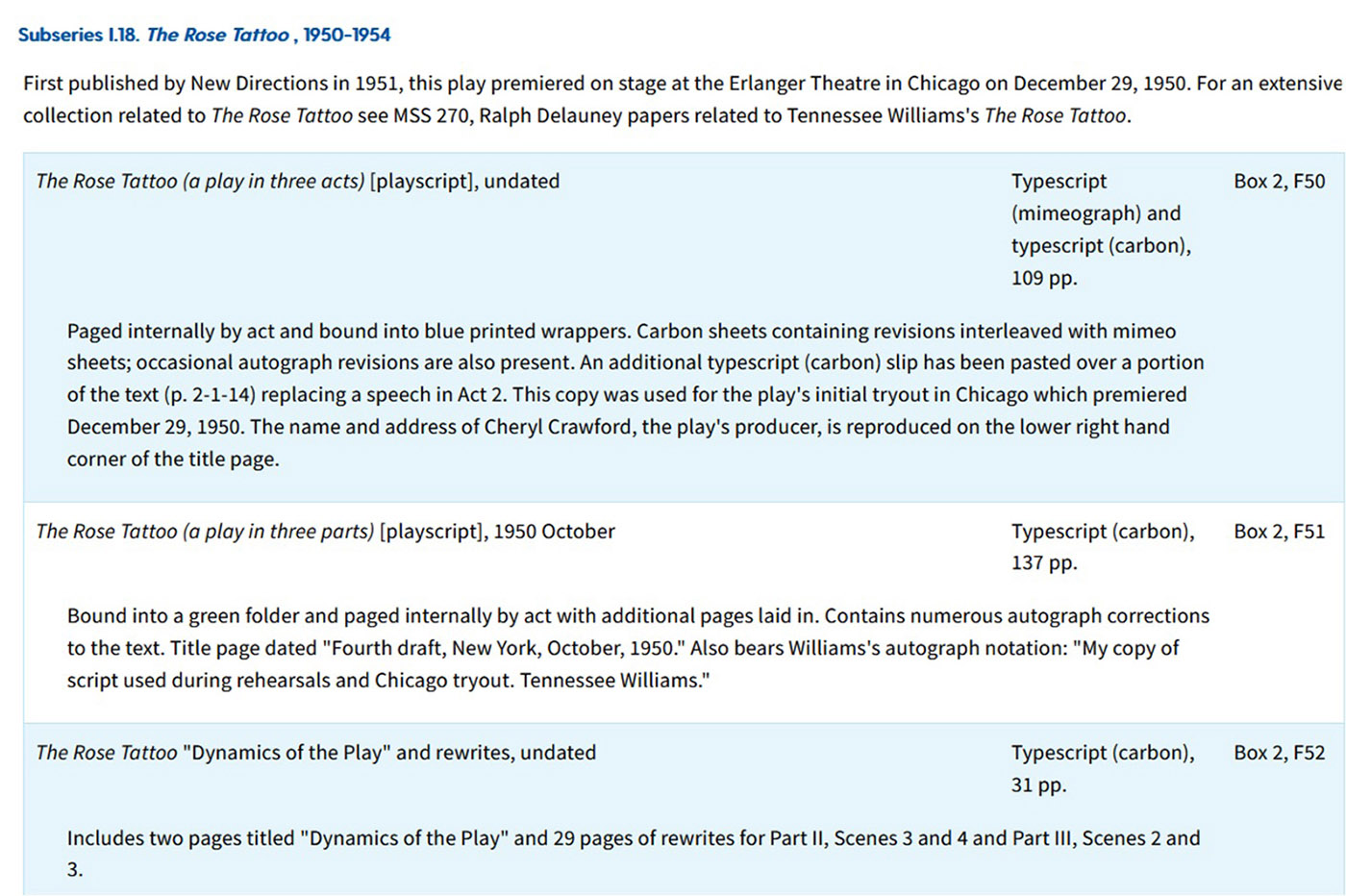

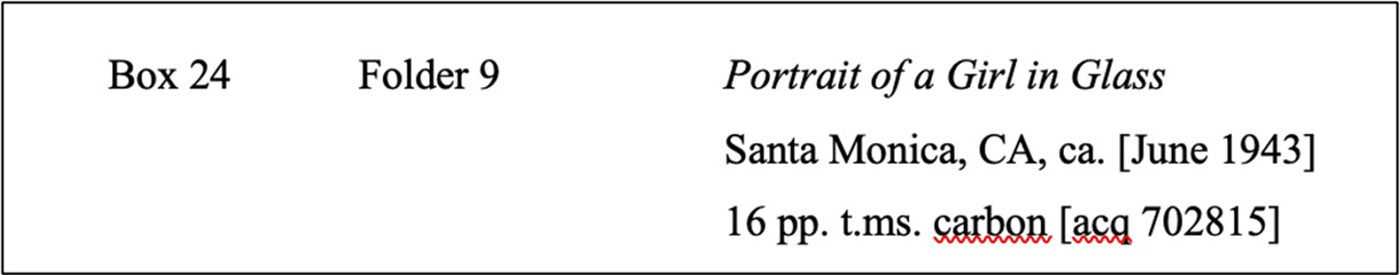

I was faced with a similar dilemma upon returning from a research visit to the HRC in August 2014, when I was able to look with fresh eyes at that flea market table of bobbles and whatsits that is the Tennessee Williams Collection. I had been to the HRC before, so I knew what to expect. I kept hearing my mother’s warning to me when I was a child: ‘Do not swim out too far from shore or you will be too tired to make it back’. Future Williams scholars would do well to heed that advice before tackling the ocean of Williams material at the HRC. Were the Collection to literally fall on someone, he or she would likely drown in the sea of paper that makes up the Collection’s eighty-one document boxes, four galley folders, three oversize boxes, and three card files (see Figure 1).

I had to negotiate my way through those card files back in 1989, when I first visited the collection to study the manuscripts of A Streetcar Named Desire for my PhD. The HRC had been collecting T. Williams’s writings (and paintings) since as early as 1962, including ‘over 1,000 separately titled works, numerous clippings, and several boxes of correspondence […] [as well as] original manuscripts and works of art by Williams, over 700 letters, scrapbooks, personal memorabilia, and 650 photographs’.5 T. Williams sold a good portion of his early and middle-career papers to the research library in 1973. Back then, the reading room was rather cramped, and readers were asked to leave personal possessions outside in an anteroom locker, bringing in only pencils and yellow scratch paper to take notes on (yellow so as to readily distinguish, upon exiting the reading room, their notes from the HRC’s white manuscripts). This was before digital cameras, of course, so photographs were not possible (although a friend of mine once tried, unsuccessfully, to videotape manuscripts with his VHS camcorder), and photocopies of individual pages were costly. You wrote down everything by hand – everything.

My advice to any scholar, new and seasoned alike, planning to visit the HRC today – now housed within its own beautiful, state-of-the-art building in Austin on the corner of West 21st and Guadalupe Street – is to add a week or more onto your original schedule. For a start, you are likely to find so much more there than you had ever imagined, and will need the extra days to allow for those distractions and detours. Even if you are disciplined enough not to be distracted by the HRC’s boundless treasures and remain focused on your Williams project, clock time and archive time are asynchronous. The time needed to read a manuscript page versus a normal page of type is easily tripled. During my 2014 visit, for instance, I was meant to look only at his nonfiction, though I admit that my eye wandered now and again while I perused the many folders delivered to me at my reader’s desk – and luckily so, since I found some interesting new material that I was later able to get published (Williams, 2015; 2016b; 2018c; 2020). So, enter the archives not only with a predetermined list of the manuscripts you want to examine, and a digital camera, but also with a reliable watch or time machine. Unlike casinos, there are clocks on the wall to consult, but, like in casinos, you won’t care, at least until the staff throws you out.

The new scholar should come to the HRC not only with a predetermined list of manuscripts but also with a bottle of aspirins, and lots of them. The Tennessee Williams Collection is maddeningly ill-catalogued by today’s digital humanities’ standards. When the HRC purchased Williams papers back in the sixties and seventies, the transactions were often brokered by Andreas Brown. A. Brown, who had inquired after T. Williams in order to produce a definitive bibliography of his work, was invited to catalogue the HRC’s papers, for which he did a commendable job. Really, commendable, given the task that he was faced with.

However, A. Brown catalogued works by title and not by genre, and when a title was missing, he opted to file the manuscript under the initial letter of the first word that appears on the page, and it was that decision that singularly caused the problems the collection faces today. Simply locating T. Williams’s nonfiction titles among his fictional and poetical works posed an enormous challenge for me back in 2014, and that is still a valid comment today. Even Drewey Wayne Gunn’s Tennessee Williams: A Bibliography (1991), one of the best cataloguing resources (despite its age) of T. Williams’s titles at the HRC (and several other archives), fails to separate fully the nonfiction from the fiction or poetry. And while Steve Mielke’s recent updating of A. Brown’s card catalogue has improved matters significantly, it still preserves A. Brown’s initial alphabetical classification by title (or first word) rather than by literary genre.

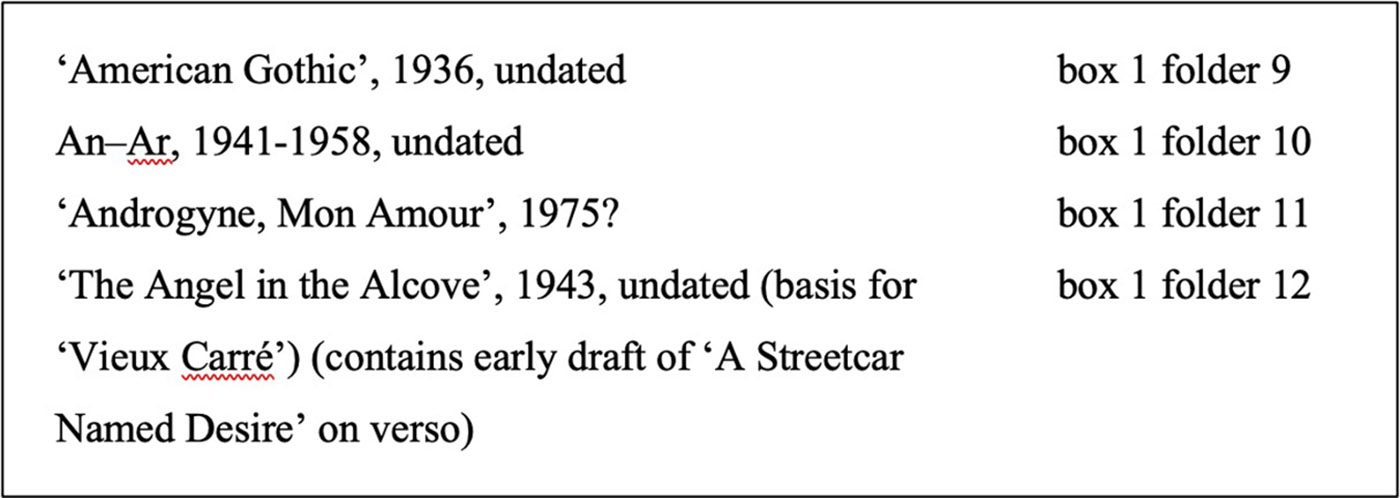

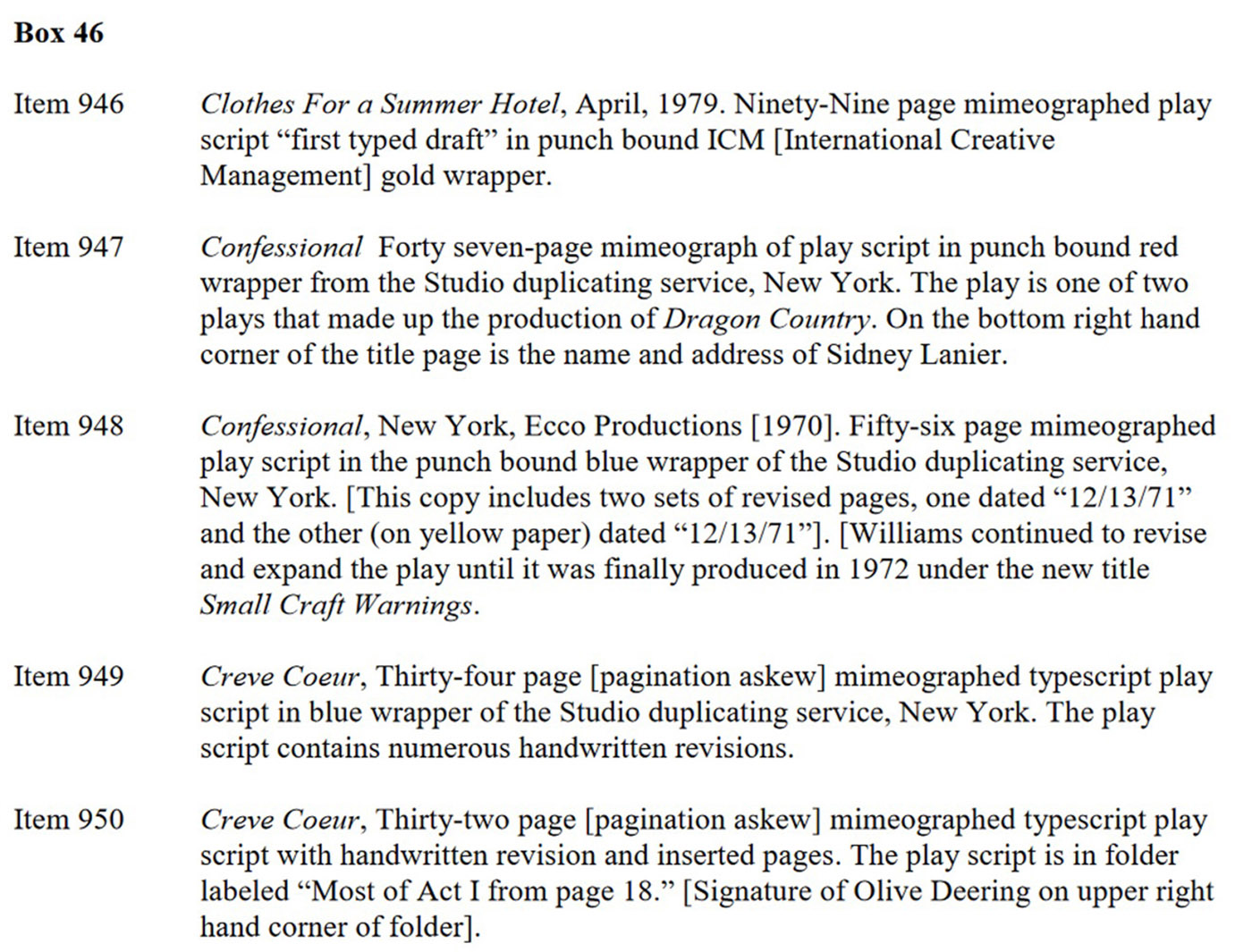

For instance, the Williams papers have been catalogued online through a useful finding aid that breaks down the collection between ‘Works, 1925–1982, undated’ (fifty-three boxes, two oversize boxes, two galley folders) and ‘Correspondence, 1880–1980, undated’ (ten boxes), among other material related to T. Williams. While the newer version of the catalogue is an improvement upon the old card catalogue system and the early digital cataloguing efforts, the result still leaves much to be desired (see Figure 2).

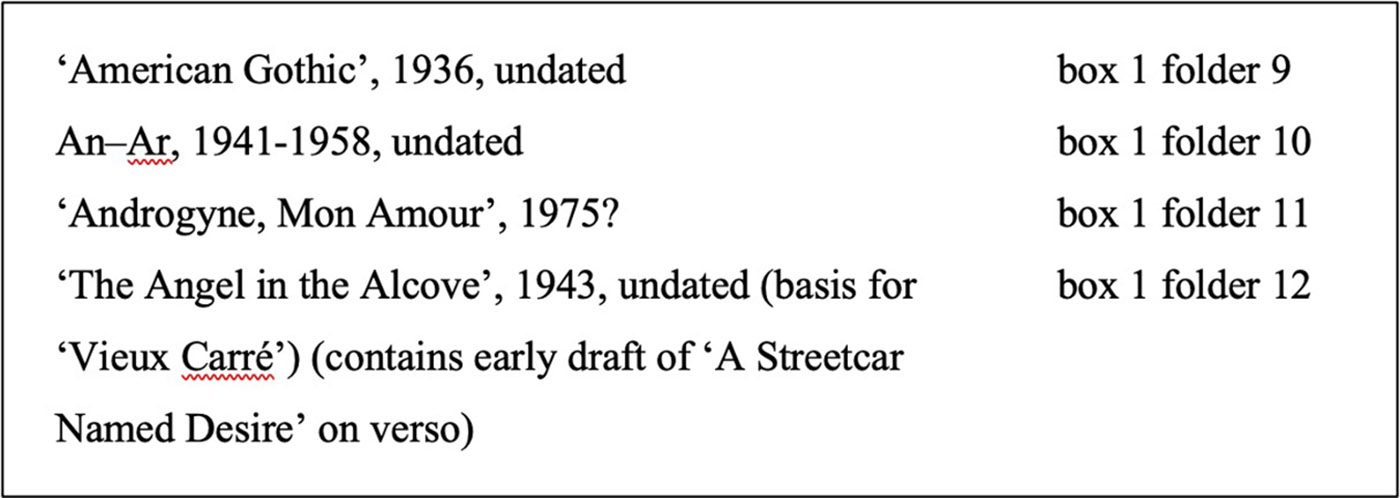

Only the seasoned Williams scholar here would know that ‘American Gothic’ is an incomplete play, that ‘Androgyne, Mon Amour’ is a poem, and that ‘The Angel in the Alcove’ is a short story. The uninformed researcher interested in consulting only T. Williams’s poetry would have to order, wait for, and then consult all three of these manuscripts to discover, much to their chagrin, that only one is a poem.

Moreover, when neither title nor genre was apparent, A. Brown simply filed the manuscripts either numerically by dates in folders marked ‘Unidentified Works’, such as those in the seven folders of Box 53, or alphabetically by their first words, placing them in folders labelled from ‘An–Ar, 1941–1958, n.d.’ (Box 1, Folder 10) to ‘Y–Z, 1938–1944, n.d.’ (Box 52, Folder 8). Many of the fragments and manuscripts located in these collective folders, which run as short as one sentence to several dozens of pages, deserve their own folders and listings, as some are poems, stories or fragments of plays. The folder ‘An–Ar, 1941–1958’, for instance, contains the poems ‘Apocalypse’ and ‘Apricots Too Sweet’ but also the short story fragment ‘An April Rendezvous’, as well as a draft of the essay ‘Art of Acting and Anna’, which should have been filed in the ‘Journalistic Article Fragments, 1945–1955’ folder, since it eventually became the piece ‘Anna Magnani, Tigress of the Tiber. She Retains “Uncanny Sense of Truth” in an English Speaking Movie Role’, which T. Williams published in New York Herald Tribune on 11 December 1955.

To complicate matters further, the folder in question also contains the incomplete poem ‘Apostrophe to Peace’, which is typed on the bottom half of the page, inverted, while, on the top half of the page is a typed letter that T. Williams (as Thomas Lanier) wrote to Constable Langston Harrison about a bill due for $6 at Helen Wolff’s women’s clothing store in St. Louis that he was unable to pay because of unemployment. Moreover, on the verso of this page (or is it the true recto?) is yet another poem, ‘Moonvines at My Door’. In all honestly, could we blame A. Brown for slipping this leaf into the folder ‘An–Ar, 1941–1958, n.d.’, when he could have opted to place it in either of the folders ‘Mo, 1941–1961, undated’ (‘Series I. Works, 1925–1982’, Box 28, Folder 7) or ‘F-H, 1937–1983, undated’ (‘Series II. Correspondence, 1880–1980, undated’, ‘Subseries A. Outgoing, 1928–1980’, Box 54, Folder 10)?

I – and others before me – have also noticed that certain orphaned manuscripts in A. Brown’s ‘Unidentified works’ files belong to other manuscript folders in the collection and should be reunited with their siblings. For instance, the item ‘These Scattered Idioms’ is catalogued separately twice at the HRC, though I have already seen versions of the same piece at the HL in Harvard, in the Fred W. Todd collection at the HNOC, and at the RBML, and I know that the title was intended to serve as a part of T. Williams’s Memoirs that he began as early as 1960 (Bak, 2012b). It was this observation that alerted me to the greater problem of the manuscripts’ diaspora over time. In T. Williams’s case, pages one and two of a given manuscript might be at the HRC, while page three is at the RBML in Columbia, and pages four and five at the HL in Harvard. The thought of trying to reunite manuscripts from his works scattered across the country is dizzying, to say the least.

Given all of this, scholars planning to conduct research in the Tennessee Williams collection at the HRC should prepare well in advance a list of the titles of the manuscripts that they wish to consult, especially if they are heading there to look only at a specific genre of his corpus. To avoid wasting precious time in the reading room, identify those titles first by looking at D. W. Gunn (1991) and then at George W. Crandell’s more complete book, Tennessee Williams: A Descriptive Bibliography (1995). If an HRC title is not found in either of these, move on to recent Williams biographies (Bak, 2013; Lahr, 2014), where many of T. Williams’s titles are often clearly identified as poems, plays or stories. And for any information about various incomplete drafts and fragments of T. Williams’s nonfiction, consult the appendix to New Selected Essays: Where I Live, where I listed all the nonfiction manuscripts and drafts that I uncovered at the HRC (Williams, 2009, pp. 293–302).6 Preparatory work is advised before visiting any writer’s archive; in T. Williams’s case at the HRC, it is essential.

The indisputable grande dame of the Williams archives, the HRC’s collection is showing its age, and will soon need that precious face-lift that T. Williams himself once contemplated. Recently, HRC curators Cassidy Schulze and Eric Colleary have begun making inroads by piecing together the many different collections where Williams material can be found throughout the HRC (e.g. in the archives of Frieda Lawrence, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Dorothy Brett, and Spud Johnson, to name just a few of the figures with whom T. Williams exchanged letters). Their cross-referencing work has proven invaluable. But more work like this needs to be undertaken. Updating the online finding aid of the Tennessee Williams Papers and Collection at the HRC is a Herculean task to be sure, and would likely require a couple years of focused, uninterrupted work, something the HRC curators simply cannot be asked to do given the sheer expanse of the HRC’s archival holdings.

A page-by-page relabelling of the Williams papers would be desirable – effectively restoring the collection to the grandeur it once held when Williams scholars were flummoxed by finding dialogue for a new play scribbled on the back of a library loan slip mixed in with train timetables, school expenses, and doctors’ prescriptions. Unfortunately, that will not happen anytime soon. In the meantime, the HRC could undertake three relatively simply but enormously beneficial tasks for researchers: first, dismantle the collective alphabetical folders (e.g. ‘An–Ar, 1941–1958, n.d.’) and create separate entries for each item; second, do the same for the ‘Unidentified Works’ folders, since we know more today about where orphan sheets belong than A. Brown did back in the sixties; and third, if reorganising the inventory per generic subseries (as is the norm today in the Williams archives) is not an option, at least supply in parentheses after each title to which literary genre it belongs. Even achieving just the last of these three tasks would be an incredible improvement to the finding aid.

For all of these reasons, the HRC is a potential diamond mine for Williams scholars, but, as with uncovering any gem, one needs to scrape through layers of rock and coal to find it. Such is not the case, however, with the other major Williams archives, where individual items are clearly identified and often labelled with detailed descriptions. It is not fair, of course, to compare the HRC’s Williams collection with theirs, since these archives arrived rather late on the scene and thus benefited not only from recent research, as well as the HRC’s cataloguing hindsight, but also from the advances made in the digital humanities.

The first of these later archives is the Rare Book & Manuscript Library (RBML) at Columbia University. The RBML began acquiring Williams papers (MS 1354) in the seventies, but the mass of its collection came relatively late, when it purchased the contents of T. Williams’s Key West home from the Tennessee Williams Estate in 1994. The collection was later expanded when Columbia purchased a small collection of T. Williams’s family letters from his brother Dakin, and when T. Williams’s last International Creative Management (ICM) literary agent, Mitch Douglas, donated several boxes of letters and manuscripts (especially those related to the writing, editing and publishing of the Memoirs). The collection is thus particularly strong in T. Williams’s late-career writings, unlike the HRC, which is strongest in his early to mid-career work.

G. Smith and Gwynedd Cannan did a commendable job back in 2000 preparing their finding aid to the catalogue of the extensive Williams collection (edited and augmented by Patrick Lawlor in 2010), though a newer version curiously exists in parallel online from 2019, which increased the collection’s original 27 linear feet to ‘160 linear feet in total, including 84 manuscript boxes, 1 map case (13-4G-13), and 119 record storage cartons’.7 The difference between the two versions is probably related to the addition of several more subseries categories, such as T. Williams’s ‘Memorabilia and Realia’ and personal ‘Library’, voluminous items no doubt catalogued only after the first wave of manuscripts were officially logged.

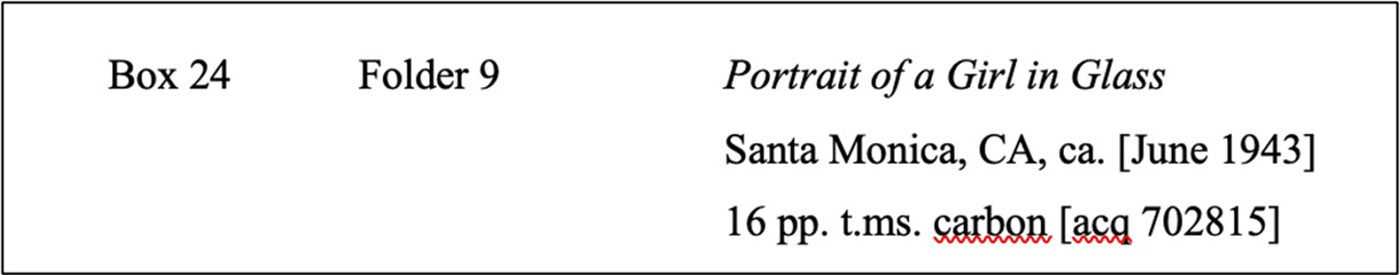

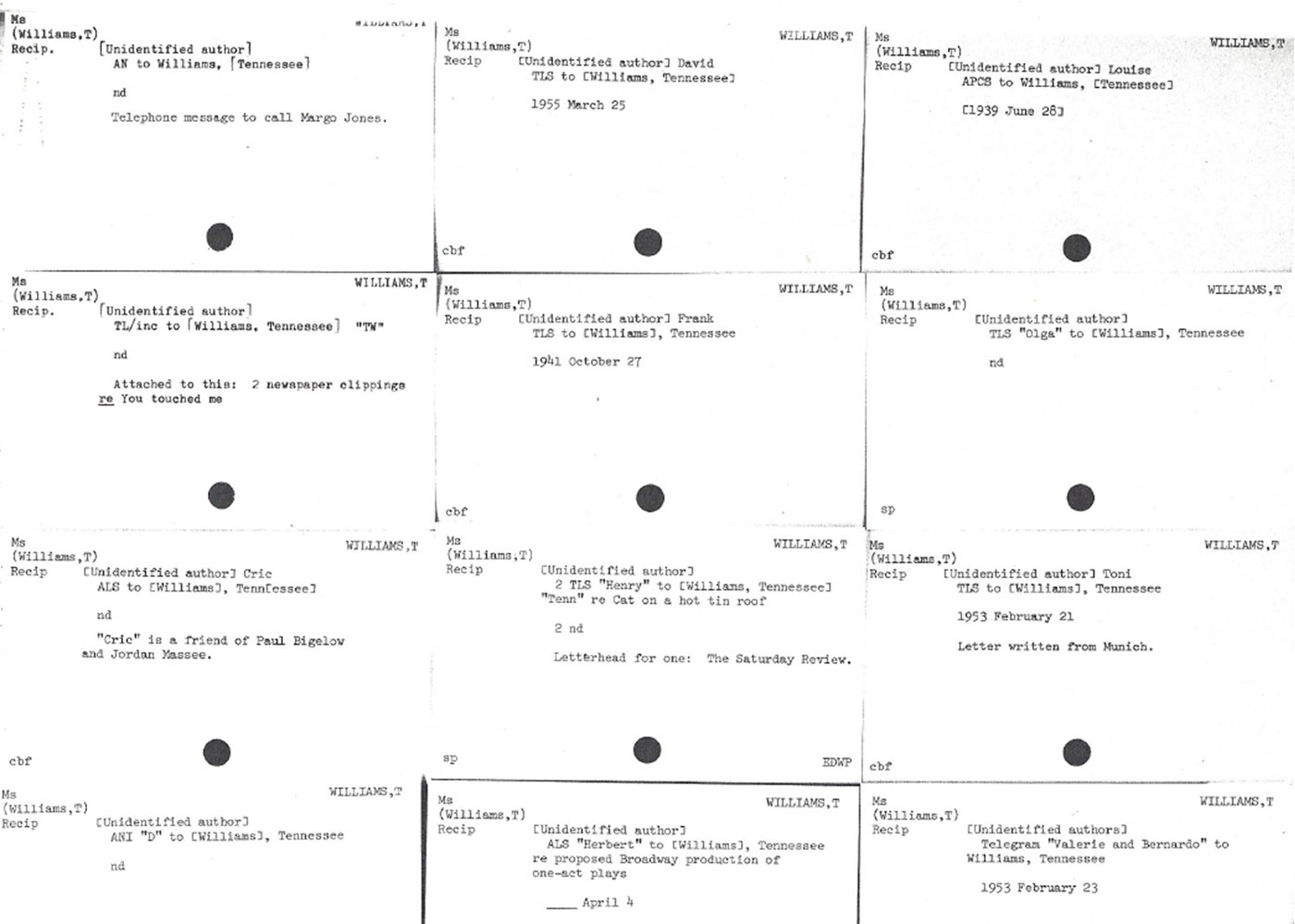

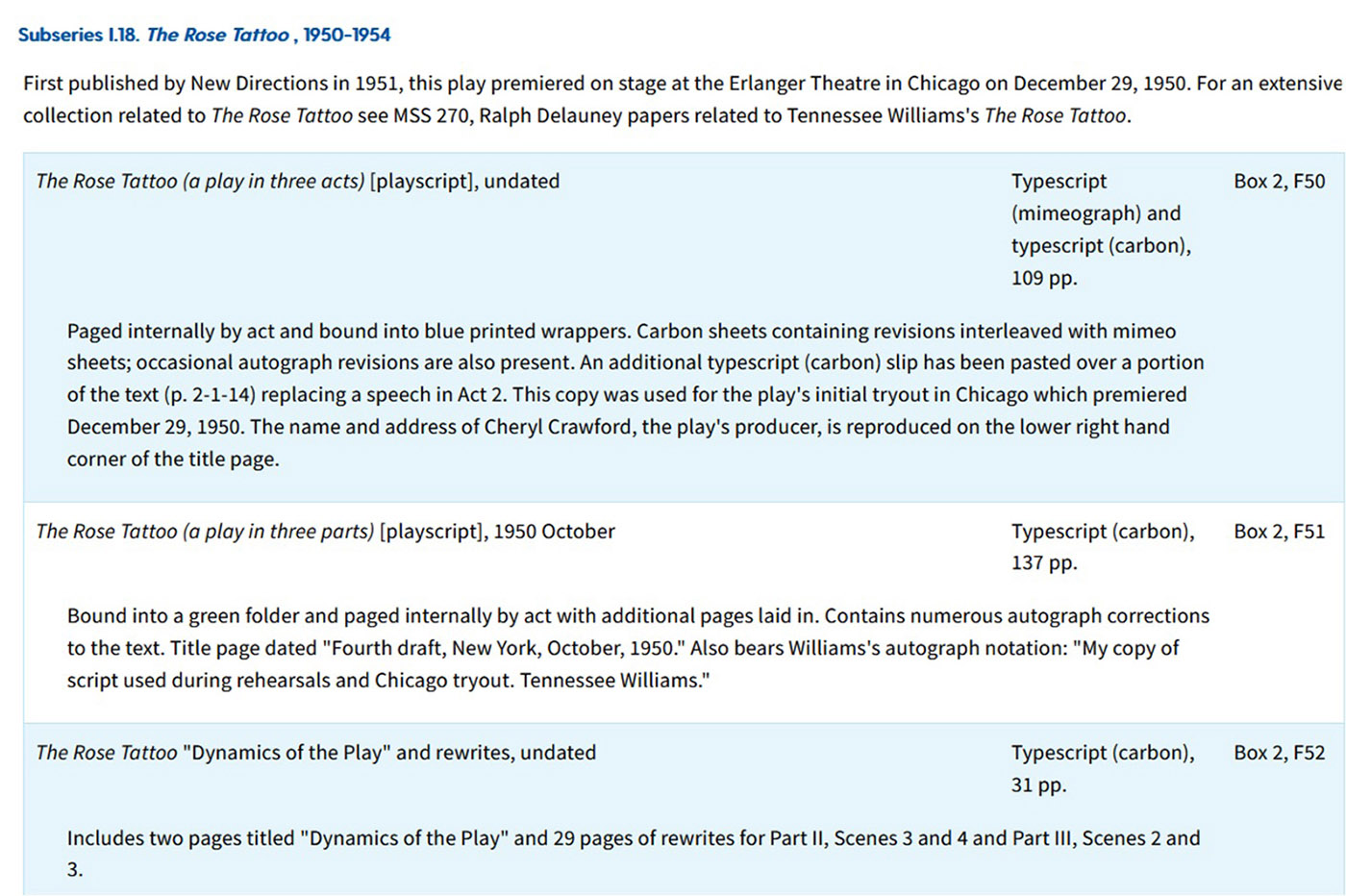

Columbia not only separates its collection into correspondences – written and received, for which it provides dates (whenever possible), correspondents’ names, and sometimes a brief summation of the letters’ contents – but also creates subcategories for the works of fiction and nonfiction, which it lists alphabetically by title: ‘Plays and Screenplays’, ‘Stories and Poetry’, ‘Other Works and Related Material’, ‘Journals, Memoirs, and Biography’, ‘Awards and Honors’, etc.

Moreover, Columbia lists important information such as the composition date (when known) and the number and paper type (carbon, mimeograph, etc.) of the manuscript pages, which is extremely important for the researcher, as it lets them know well in advance how much time will be required to read a given file at their reader’s desk. It also cross-references entries when a work is known by two or more names: ‘Boom, [n.p.], [n.d.], Script pages, notes [See also The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore]’. In short, the RBML’s online cataloguing of their Williams collection is exemplary (see Figure 3).

Equally impressive are the Tennessee Williams Papers, 1932–83 at the Houghton Library of Harvard (MS Thr 397 and MS Thr 493). Nearly half of their 20 linear feet is dedicated to T. Williams’s plays, especially working drafts from the fifties onward. Like the RBML, the HL is strongest in its mid- to late-career material, and it too divides its collection into compositions and correspondences, going even further by subdividing its fictional compositions into specific genres: ‘Theatrical Plays’, ‘Screenplays’, ‘Television Scripts’, ‘Essays’, ‘Novels’, ‘Poetry’, and ‘Short Stories’.

The online cataloguing came rather late at Harvard, which is also one of the reasons why it is more up to date than the HRC. As Harvard curator Dale Stinchcomb writes, ‘the playwright himself gave several typescripts in 1963 and bequeathed a significant collection of manuscripts to Harvard upon his death’. Over the years, the library has continued to add to these holdings.8 As the story goes, in 1980, T. Williams promised the majority of his remaining manuscripts to Harvard (which was eventually actualised in May 1988 via a Monroe County Circuit Court order in Florida) as quid pro quo for the honorary doctorate he received from Harvard in 1982, less than a year before his death. The massive and important collection, unfortunately, sat idly in boxes, and left entirely uncatalogued for more than a decade until the death of Lady St Just in 1995.

This collection at the HL was processed by Rick Stattler and, according to the collection’s website, ‘partially processed on at least two other occasions between 1985 and 2006, including work by Doug Rand, who supplied “HTC” catalog numbers. It has been used frequently by researchers during that time, so wherever possible the previous box and folder numbers have been recorded, as well as the asset numbers from the original estate inventory’.9

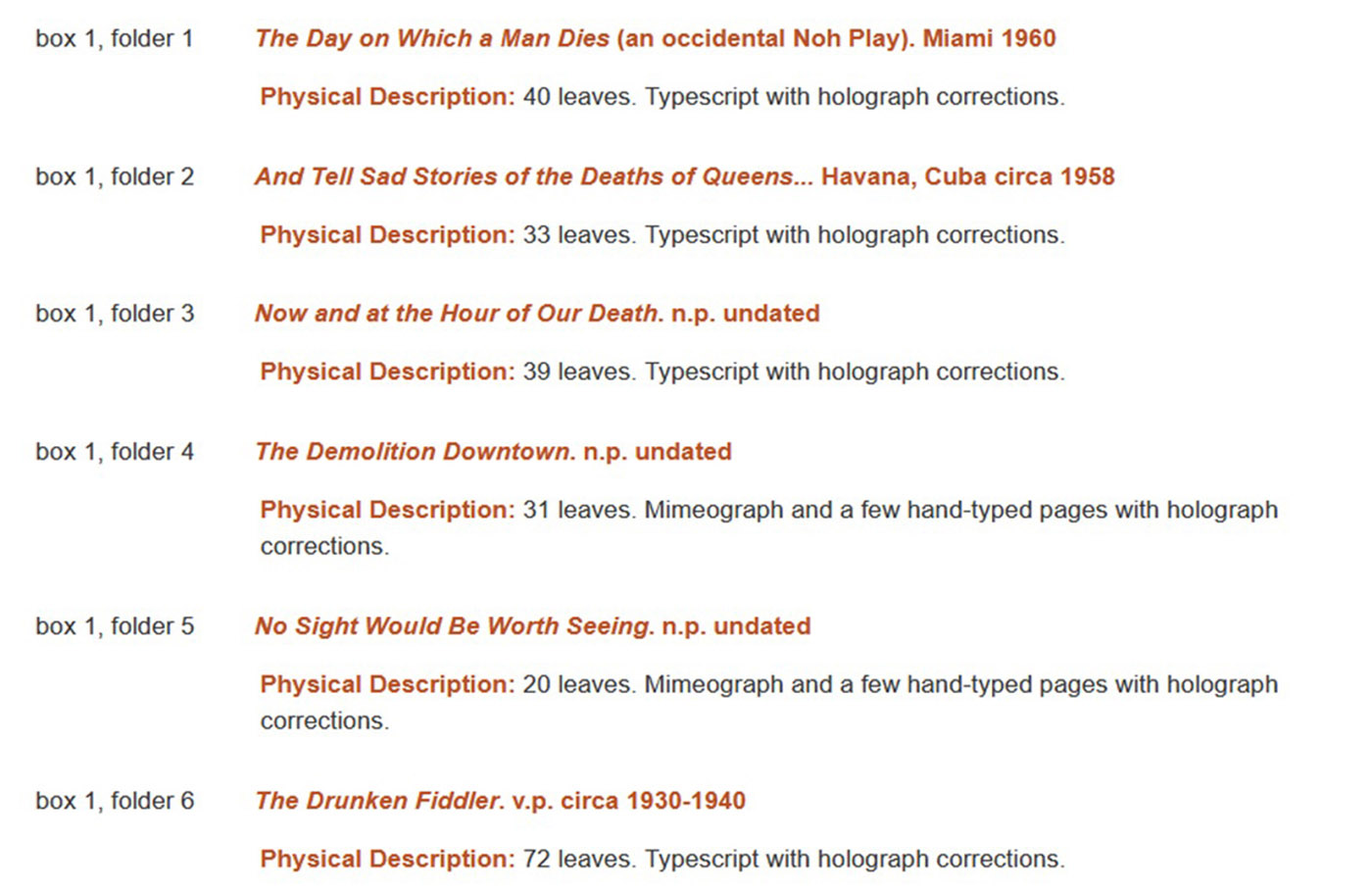

Because of their late cataloguing, the Williams papers at Harvard benefited from the digital humanities, and, like the Columbia collection, it offers scholars important details about dates, contents and even acquisition information (see Figure 4).

Despite the benefits of its generous item-by-item descriptions, the collection is not without its flaws. Certain manuscripts, like the prose poems ‘What’s Next on the Agenda, Mr. Williams?’ (HL, items 792 and 793) and ‘Arctic Light’ (HL, item 707), are misfiled in the subseries ‘D. Essays’. Moreover, many of the nonfiction drafts are misdated – some by only a year; others by several. No attempt at cross-referencing is made outside the collection, even though some of the mimeographed manuscripts are exactly the same as those at the HRC (e.g. ‘Experiments of the Sixties and Further Plans’ (HL, item 717 and HRC, Box 51, Folder 13)). Other manuscripts are entirely different though they share a similar title (e.g. ‘A Letter to Irene’ (HL, item 732) vs. ‘Letter to Irene’ (HRC, Box 23, Folder 8)). Some items at the HL are clearly from early drafts of a given manuscript (e.g. ‘Finally Something New’ (HL, item 719) vs. ‘Finally Something New’ (HRC, Box 51, Folder 13)); or later drafts (e.g. ‘The Sculptural Play’ (HL, item 759) vs. ‘The Sculptured Play’ (HRC, Box 40, Folder 8)); or even pages from one file misplaced or misidentified in another file (e.g. a sheet from ‘Unidentified essays’ (HL, item 818) is actually the missing page ‘2’ of the manuscript filed in ‘An allegory of man and his Sahara’ (HL, item 705)).

Given that, at the HL alone, the number of manuscript pages filed in these ‘Unidentified’ folders numbers in the hundreds, the task of sorting through them all and identifying, whenever possible, which pages belong with which manuscript would be terribly time-consuming. In order to limit as much as possible the potential errors in missing the connections between manuscripts examined a year apart, the curators would need to establish an extensive methodological database, including physical evidence to be noted, such as paper type (cotton or onion skin), hotel stationery (a practice T. Williams continued throughout his life was to take a wad of stationery from the hotels he stayed at and type on it instead of buying his own paper), or typewriter keystrokes (during the later fifties and early sixties, he used a typewriter that had small-capital letters instead of full upper- and lower-case letters). Together with the contents of each page, the physical evidence could greatly help reunite files dispersed among the archives and establish a more complete manuscript to analyse later.

While the HRC, RBML and HL round out the top three ‘must-visit’ archives for Williams scholars, another major collection of Williams papers and realia should not be ignored. The Historic New Orleans Collection officially began collecting Williams papers in 1994 with ‘the purchase of a ninety-nine-page playscript of Vieux Carré from The Brick Row Book Shop in San Francisco’ (Cave, 2005, p. 72). After purchasing several lots of T. Williams’s manuscripts from the Neal Auction Company in 2000 (Accession number 2000-33-L), the collection was well established. The HNOC soon confirmed its prestige with the acquisition of The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection (MSS 562).10 Curators Mark Cave and Jessica Dorman have been in charge of the Williams collections for many years now, and both gathered together with Dale Stinchcomb (Harvard) and Eric Colleary (HRC) in the scholars’ panel ‘Holding Tennessee: Exploring the Williams Collections’ back in 2019 at the 33rd Annual Tennessee Williams & New Orleans Literary Festival to compare their various Williams holdings.

The Todd collection itself comes from Fred W. Todd, a Texas librarian and avid collector for over forty-four years of all things Williamsian, from manuscripts and letters to memorabilia and realia. A faithful attendee to the annual Tennessee Williams & New Orleans Literary Festival, F. W. Todd worked out a deal with the HNOC in 2000, wherein he would bequeath them the majority of his collection. In his article ‘Fred W. Todd and the Tennessee Williams Holdings at The Historic New Orleans Collection’, Mark Cave provides the narrative behind the collection’s arrival at the HNOC in February 2001, as well as its later expansion and cataloguing, first by M. Cave and F. W. Todd, then revised and updated by Jason Wiese in March 2018. Any researcher planning to come to New Orleans would be well advised to read M. Cave’s article in advance.

The Williams material was originally organised into four series: plays and screenplays, short stories and novels, poetry, and nonfiction, although the online finding aid today lists twenty-six different series from ‘Periodicals’ to ‘Posthumous Additions’. Unlike the other major Williams archives, the HNOC does not have an interactive online finding aid. Its line-item finding aid for each series, which also lists manuscripts and other documents alphabetically by title or correspondent’s last name (or chronologically for periodical publications), is instead reproduced on multiple downloadable PDF files. Individual items, limited to two at a time, are to be ordered in-house only by filling out a call slip. On these PDF files, the individual manuscripts and items themselves are fully detailed, from the number of pages, paper support, and composition dates (when known) to a summary of their contents (see Figure 5). While the technology may not be as advanced as in the other archives, the abundance of information provided largely makes up for the inconvenience in ordering the files. And although the collection is smaller in linear feet than the other three, it is as rich and eclectic, covering the entire span of T. Williams’s lifetime. It is a must-visit for the Williams aficionado and scholar alike.

In addition to these large archival collections are much smaller Williams collections scattered about the country, including at his alma mater, Washington University, in St. Louis. Of special note are two other archives, the University of Delaware’s Special Collections (4.6 linear feet) and at the Special Collections Library of the University of California, Los Angeles (1 linear foot).

The six boxes of the University of Delaware’s Tennessee Williams Collection (MSS 0112) span the dates 1939–2013 and ‘[consist] of an extensive collection of correspondence, manuscripts, photographs, printed material, and ephemera related to American playwright Tennessee Williams’.11 The collection, which dates from the early sixties but consists largely of a 1979 acquisition from famed New York collector Norman Unger, was initially processed by Timothy Murray. T. Murray also prepared the catalogue for the Library’s exhibition ‘Evolving Texts’, which ran from 1 August to 15 November 1988 and whose ‘underlying theme’ was ‘the ongoing development of Williams’s written texts’ (Murray, 1988, n. pag.). Evolving Texts: The Writing of Tennessee Williams catalogues nearly a hundred items from the collection, including several illustrations and detailed descriptions of each item, such as the twenty-five-page typescript ‘Suitable Entrances to Springfield or heaven’ (Box 3, Folder 62), about Vachel Lindsay’s suicide by drinking Lysol, the only known extant copy of the play in the public archives and one of UDEL’s literary jewels.12

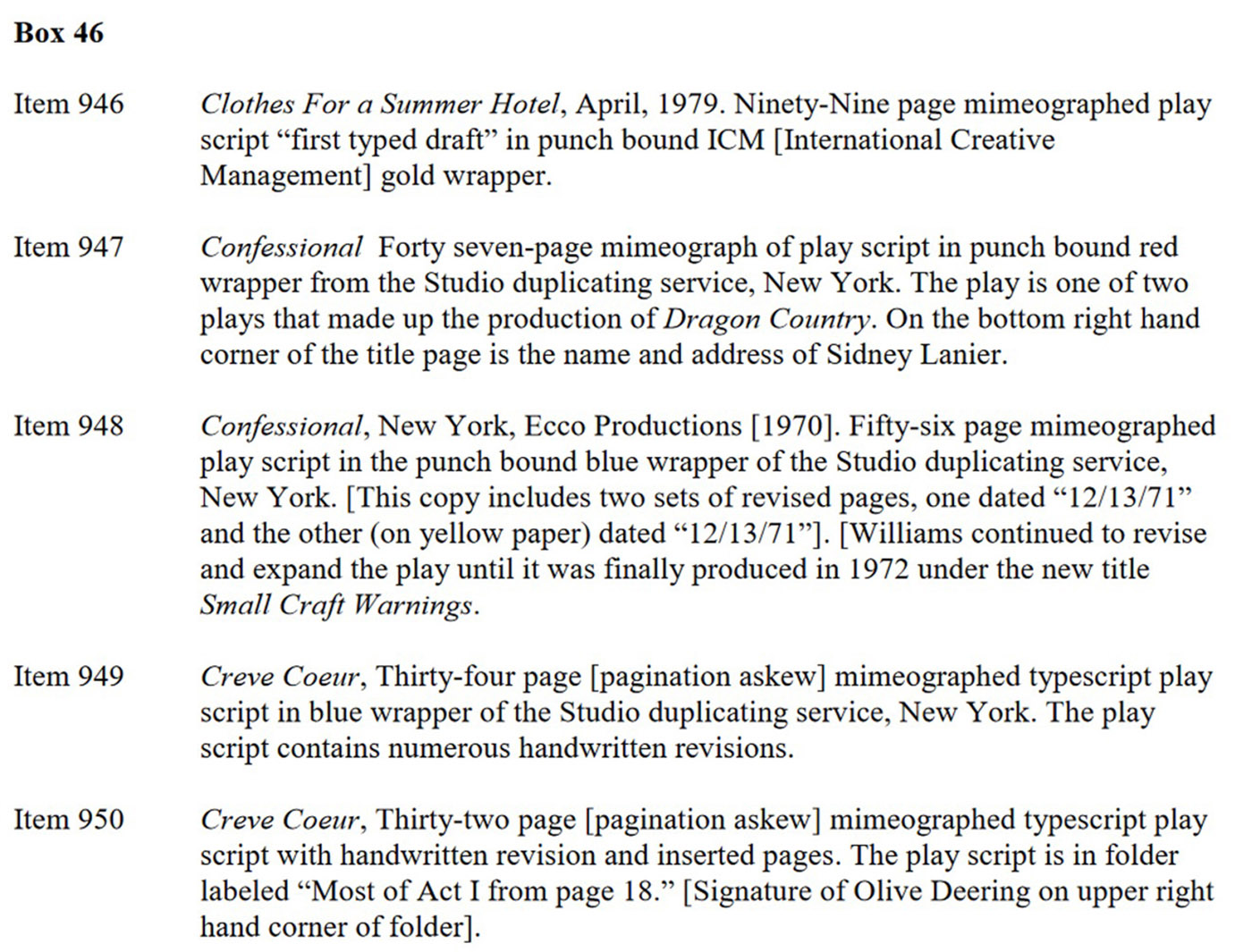

The collection’s online Manuscript and Archival Collection Finding Aid – revised by Anita A. Wellner between 1993 and 2013 and encoded by Lora J. Davis in May 2010 – is divided roughly in half between manuscripts and ‘supportive material’,13 and the manuscripts are arranged into three series: ‘Series I. Dramatic Work’, ‘Series II. Fiction’, and ‘Series III. Miscellaneous Correspondence, Manuscripts, and Ephemera’. Dramatic works are arranged alphabetically by title, with more significant plays containing subseries whose material is ordered chronologically. What is particularly useful here is the detailed description offered for each manuscript, including the paper support (e.g. typescript, mimeograph, carbon), the number of pages, the date (if available), as well as extensive notes about the manuscript itself (see Figure 6).

It is likely that UDEL’s online interface is so detailed because much of the early legwork had already been done by T. Murray, whose descriptions of the manuscripts in Evolving Texts no doubt informed the ‘Contents’ page of the collection’s website. Another reason is that the collection’s holdings are relatively small in comparison with the HRC, RBML and HL, and the encoding task was therefore more manageable. Sadly, the same could not be said of the Tennessee Williams Paper, 1930–70 (Collection LSC 0492) at the Special Collections Library of UCLA. Measuring a single linear foot within two boxes, the online finding aid lists only the bare essentials of its manuscripts, making it perhaps the least user-friendly of all the Williams archives.

The history behind UCLA’s collection is worth mentioning. In September 1970, the day after an interview he had given to Don Lee Keith in New Orleans, T. Williams headed for the Orient aboard the SS President Cleveland with long-time poet-professor friend Oliver Evans. As apocrypha has it – partly advanced by the playwright himself – the trip was paid for from the $10,000 that O. Evans raised by selling several of T. Williams’s manuscripts to UCLA (Bak, 2013, p. 212), which are now housed in room A1713 of its Charles E. Young Research Library’s Special Collections. T. Williams mentions in a letter to Virginia Carr held in the collection (MS 30, Box 2, Folder 16) that he and O. Evans were leaving on 10 September (Williams, 1990, p. 207). In another letter in the collection written by T. Williams to research librarian Jerome Melvin Edelstein14 and dated 9 September 1970, and accompanied by a three-page list of thirty manuscript descriptions, T. Williams ‘confirm[s] the Mss. in this collection to be [his] work as described in the catalogue that accompanies it’ (Box 1, Folder 0). Both letters attest to the truth that the transaction was much more formal than rumour had it.

In fact, each of the thirty manuscripts is placed in separate manila folders bearing T. Williams’s handwritten title and number corresponding to his master list sent to J. M. Edelstein. Apparently, Audrey Wood had sent to T. Williams, via certified mail to his Hotel Roosevelt address in Hollywood, an envelope postmarked 8 September 1970, containing at least one play, ‘No Sight Would be Worth Seeing’, where the earlier title ‘Green Eyes’ is crossed out. Given that several of the manuscripts were bound in blue ‘Liebling-Wood’ wrappers, it seems that A. Wood had sent him all of these as well, since it is unlikely that T. Williams would have carried them on his person at the time (unless he knew in advance about the sale, which is possible). Another legal-size envelope was sent from Honolulu on 15 September, this time from O. Evans to J. M. Edelstein, probably carrying another manuscript as well.15

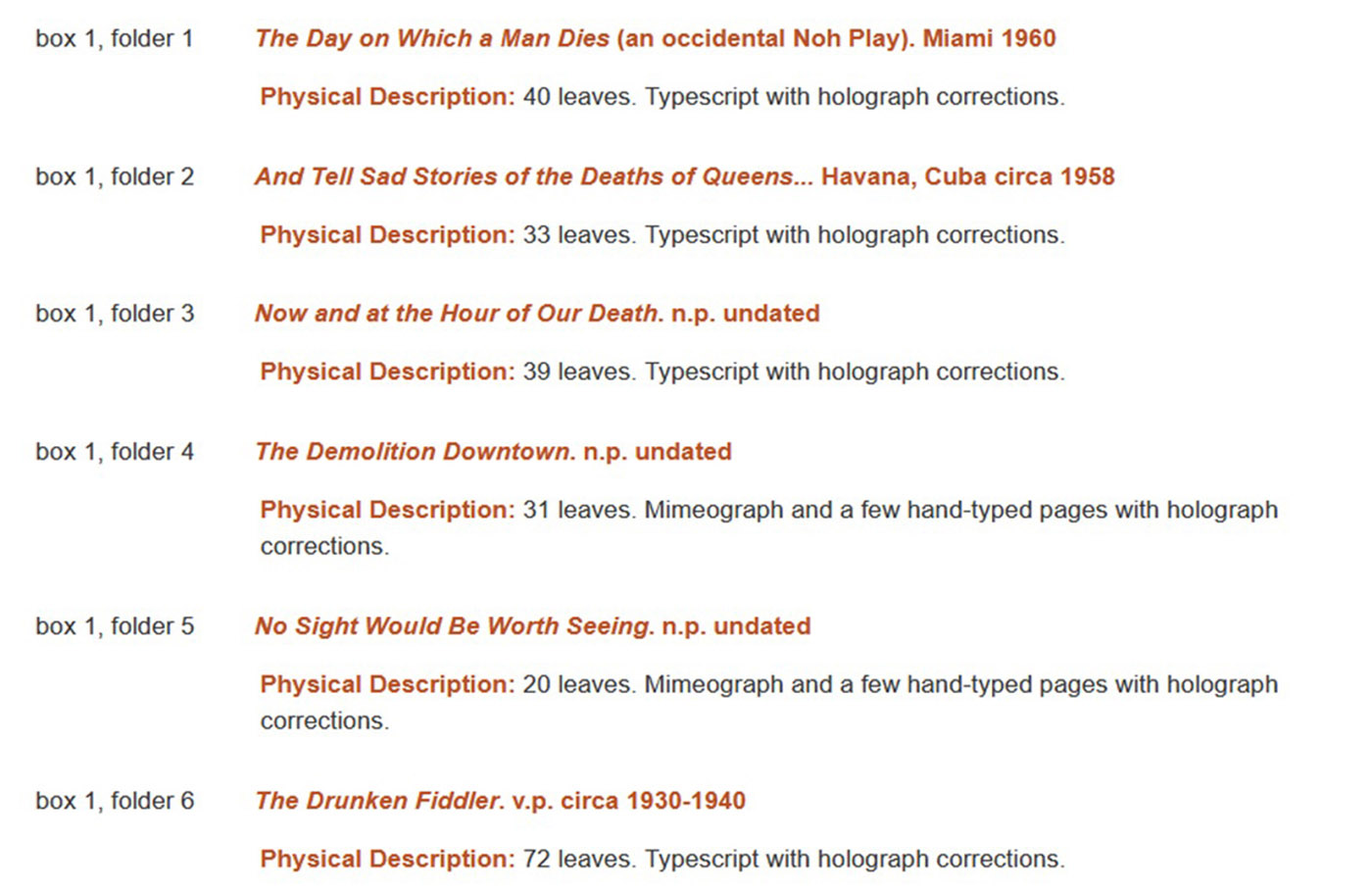

The actual finding aid of the UCLA collection is of little use here, as it lists only pages and potential dates of the various manuscripts, with a brief ‘Physical Description’ commentary tacked on (see Figure 7). Future scholars would thus be advised to target the UCLA collection only for a specific manuscript that it contains.

Undertaking any advanced study of T. Williams’s work today likely requires a trip to one or more of the archives mentioned. As this essay has attempted to show, assembling Williams papers spread out across the various archives for even just one of his plays or nonfiction pieces is no easy task: it is akin to a palaeontologist’s attempt to reconstruct a full or partial skeleton of a dinosaur from the bones extracted from the earth. With respect to Williams papers, however, the process is even more complex: imagine the discovery at one dig of the partial skeletons of several different species of dinosaurs from various epochs whose remaining bones were equally mixed together and scattered about the continent. The job confronting the future Williams scholar is to sort through all these ‘bones’ preserved in the various ‘digs’, classify them by species, and reassemble them as fully as possible back to their original form.

One of the easiest ways to collate these T. Williams’s manuscripts is to compare their style and content, a sort of carbon-dating exchange of DNA, if you will. Finding similar key phrases, paper support, typewriter keystrokes, or even titles in two or more manuscripts would certainly suggest a shared heritage. While this may work with some of T. Williams’s manuscripts at times, at other times it clearly does not. One obvious example is that he used, and reused, the same title for material that was not only unrelated but also written over a decade apart. For example, fragments entitled ‘These Scattered Idioms’ are housed at the HNOC, the RBML, the HL (which owns five different versions alone) and the HRC. While the title, which comes from a Hart Crane poem, refers to T. Williams’s early drafts of his Memoirs, he reused it several times for writing that amounted to little more than his daily impressions. All of these items share a common ancestor, to be sure, but establishing how they are linked is problematic.

Other problems are raised when multiple versions are clearly recognisable but the order in which they were written remains uncertain. There are various manuscripts in several archives that are clearly photostats of an original, but T. Williams often kept the originals from which the photostats were made, and then placed the photostatted copy into his typewriter and began writing from it. At other times, he added further revisions to the original version after a photostat was already made. For example, as noted above, the HL owns an essay fragment titled ‘Finally Something New’ (item 719), written around August–September 1976. It is typed on onion-skin paper and is the original version of the same essay at the HRC. The HRC version, however, does not contain the final two pages of the HL version, which offer later variations to the second and third pages of the HRC draft. And this incident is not an isolated case. The most difficult task facing future Williams scholars is to identify, between the various archives, which file is connected with which, and which is the first draft and which are later versions. While the HL was able to recognise that this piece belonged to an essay series that T. Williams did not complete, the HRC did not, and thus was unable to catalogue the piece as nonfiction.

Other files suggest a similar case, though contrary in nature. At the HL, there is a file entitled ‘A Letter to Irene’ (item 732), a typescript dated December 1940. The manuscript is an attempt at a short story that T. Williams was working on based on his first visit to New Orleans in December 1938, when he met an artist-prostitute named Irene. The HRC possesses a similar manuscript with the same title, ‘Letter to Irene’, but it is not the same text. What is important here is that Irene was to become a heroine of T. Williams’s southern trilogy, which was to include ‘The Aristocrat’ (Tennessee, 2006b, pp. 170–71). Eventually, she was worked into the character Blanche DuBois from A Streetcar Named Desire. Both the HRC and the HL piece should be collated and filed together under works of fiction along with, or separate from, the draft versions of the more famous play.

All news Williamsian is not daunting, however. The important work being done today by the various archives’ curators – Eric Colleary at the HRC; Jenny Lee and John Tofanelli at the RBML; Dale Stinchcomb at the HL; and Mark Cave and Jessica Dorman at the HNOC – is making life much easier for the Williams scholar. And the finding aids themselves are improving with time as the digital humanities become more user-friendly. So long as no plans are in the works to digitise all of T. Williams’s manuscripts and make them available online, as was done with Samuel Beckett’s papers (https://www.beckettarchive.org), the future Williams scholars will still have to content themselves with travelling to places like New York City, New Orleans, Boston, Austin, and Los Angeles – and that is definitely not a bad thing.