Julian Barnes, Kazuo Ishiguro and Ben Okri

In Starbook (2007), Nigerian author Ben Okri imagines a tribe of artists whose life and craft are regulated by a number of tenets, one of which is imperfection. The narrator explains: ‘Imperfection was a great law of the tribe; and so they were always learning to unlearn. They begin as masters and end as children’ (pp. 98–99). Although often negatively connoted, imperfection can be valued as an incentive to revise and ‘perfect’ one’s work, even if perfection may not be what an artist is striving for. In Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot (1984), the narrator berates critics who point out inconsistencies in books, referring to a lecture entitled ‘Mistakes in Literature and Whether They Matter’ (1985, p. 76), and exasperatedly exclaims: ‘Look, writers aren’t perfect’ (p. 76). Okri himself believes that perfection, being ‘all angles and mathematics and geometry and phoney framing and not taking risks’, is ‘the enemy of art’ (Falconer, 1997, p. 47). As underlined by Daniel Ferrer in this volume, there exist modalities of imperfection, ranging from agrammaticalities and factual mistakes to what a writer may consider as flaws pertaining to structure, character, theme, plot, style or voice, which lead them to relentlessly revise a draft or discard it altogether.

This paper will focus on what the writer as reader and critic of their own work considers imperfect in their creation and examine what specific actions the sense of imperfection may trigger in them, from relentless revision to outright rejection. I will consider two main temporalities in the judgment of imperfection and proceed backwards, from the writer’s view on their published work when revisions to that specific edition are no longer possible to their assessment of drafts when the writing is in progress and imperfections can still be ironed out. For this study, I will examine the creative practices of the contemporary writers Julian Barnes, Kazuo Ishiguro and Ben Okri in order to compare their reactions to imperfection. I will first focus on their retrospective gaze over what they may perceive as the faults of their published work, with a possible impact on their later creations, before exploring the necessary and intrinsic imperfections of the creative process, which lead writers to make revisions at the micro- or macrolevel, or take the decision to dispose of a passage, a chapter or an entire book.

Writers rarely openly admit to the imperfections of their published work, at least at the time of publication, though they may acknowledge them retrospectively. In some cases, a sense of dissatisfaction can incite a writer to revise their work several years after its original publication. As noted by Ferrer, ‘any repentance, even if it is late, even if it comes after publication, […] re-establishes a space for invention’ (2011, p. 57, my translation).1 In 1996, Nigerian author Okri issued a revised version of his second novel The Landscapes Within (1981) under the new title Dangerous Love because he felt he had not properly realised and actualised the idea that had been given to him. He described the revising process as ‘the closest thing you can do to a complete public and private self-flagellation’ (Falconer, 1997, p. 47). In the ‘Author’s Note’ to Dangerous Love, he remarked about the earlier work (completed at the age of twenty-one): ‘[It] has continued to haunt and trouble me through the years, because in its spirit and essence I sensed that it was incomplete […]. The many things I wanted to accomplish were too ambitious for my craft at the time’ (p. 325). The changes he made to try and ‘redeem’ the earlier book (p. 325) were not related to plot, characters or chronology but involved ‘the addition of or […] the importance given to certain statements, events, conversations, metaphors, the explicitness of theoretical considerations and their manifestation in the artist-hero’s mind’, as well as stylistic variations (Tunca, 2004, p. 86).

While such a revision may have been prompted by what Okri viewed as a lack of experience or expertise in his early years, a different process led him, in 2022, to publish The Last Gift of the Master Artists, a revised version of his ninth novel Starbook, issued fifteen years earlier. Although Okri felt Starbook was one of his most important works, he regretted that critics did not ‘reference the slavery aspects or saw them as allegorical’ (Thorpe, 2022), and he therefore decided to revise the text to give more emphasis to what had been overlooked and modify ‘the tonal quality of the whole book’ (Guignery, 2024, p. 206). As in the case of Dangerous Love, the changes do not pertain to plot or characters but to style, tone and the greater importance given to specific sentences or words. While Dangerous Love, compared to The Landscapes Within, was marked by the addition of some narrative sequences and the ‘introduction of extra themes such as slavery’ together with stylistic condensation (Tunca, 2004, p. 97), The Last Gift of the Master Artists is more concise and compact than Starbook, as many passages were deleted and almost none were added. Visually, the book is less dense: long paragraphs were divided into shorter ones and sections were cut into several separate ones, so that the book contains blanks and spaces which give the reader an opportunity to reflect on what they have just read. These blanks can also be seen as a physical materialisation of the gaps that are evoked in the text (historical gaps, gaps between different places or realities, gaps created by disappearances, etc.), a concrete device Okri had not thought about when writing the original novel (Guignery, 2024, p. 207).

In addition, while Starbook, like other earlier examples of Okri’s work such as the Booker-Prize winner The Famished Road (1991), often relies on lexical enumeration (through an accumulation of coordinated or uncoordinated nouns or verbs), The Last Gift of the Master Artists sometimes pares this down to a single item, thereby giving more emphasis to the preserved element. For instance, when the narrator of Starbook refers to the sculpture of three men and a woman bound together by chains at the ankles, verbs compulsively aggregate in a hyperbolic mode: ‘The sculpture accused, haunted, frightened, soothed, troubled, perplexed, annoyed, paralysed, trapped and engulfed them’ (2007, p. 84). In the revised book, the sense of overwhelming saturation conveyed by the earlier enumeration is cancelled as a single verb has been kept: ‘The sculpture paralysed those who gazed on it’ (2022, p. 78), making the sense of paralysis possibly more powerful and arresting. This process of reduction (which is also a ‘redistribution process’ as Okri shifted elements around (Guignery, 2024, p. 207)) is recurrent in the new version and mirrors the author’s evolution: ‘“I’m older and something has happened to my own voice as a writer – it’s deepened and gotten abridged and simplified at the same time”’ (Tepper, 2023). Between the original book and its revised form (under a different title), ‘[t]he scriptural “I” has become another’ (Grésillon, 2007, p. 32, my translation).

Regret at the imperfections of one’s published work rarely leads to such a ‘painstaking and agonizing process’ (Thorpe, 2022) as Okri’s belated revision of his books, and Barnes’s approach at the start of his career was strikingly different. His first (unpublished) book was ALiterary Guide to Oxford for which, in the early 1970s, he had gathered material, anecdotes and quotes from and about writers who had lived in or near Oxford or had read or taught at some of the colleges. The publishing process following the submission of parts of his manuscript in September 1971 was harrowing and Barnes was aware of the imperfections of his work as he wrote in the margin of the first completed version indications such as ‘poor’, ‘still poor’, ‘extend?’, ‘redo’, ‘expand with quotes or descriptions?’, ‘reorder?’, ‘?cut some of these’, ‘?improve’, ‘?dull’, ‘no, boring’ (8.3).2 When Harvester Press agreed to take on the book in November 1973, the publisher required substantial revisions. The letter Barnes sent with the revised manuscript on 9 September 1974 was stern and uncompromising: ‘Here is the final, complete, improved, expanded, perfected and unimprovable version of the Literary Guide. It’s been quite a slog – lots of new material included, every page rewritten and (I hope you will tell me) more accessible and readable now’ (17.1). Despite the fact that the version was ‘perfected and unimprovable’, when Barnes wrote a letter to Harvester Press in August 1976 intimating to either publish or immediately return the typescript, the Press promptly opted for the second option.

A few years later, when Barnes submitted his first novel Metroland (1980) to Jonathan Cape at the age of thirty, he had worked on it for seven to eight years, with long periods of time when he had put it aside, and had ‘worried about it, liked it, despised it’ (2016a, p. 1). He recalls: ‘It was a long and greatly interrupted process, full of doubt and demoralization… I had absolutely no confidence in it. Nor was I convinced of myself. I didn’t see that I had any right to be a novelist’ (Guppy, 2009, pp. 66–67). When, in 2016, he looked back on the time when he ‘finished’ the novel, he placed the verb between inverted commas and glossed it as ‘a posh way of saying “abandoned through fatigue”’ (Barnes, 2016a, p. 2). After his editor Liz Calder said she was pleased with Barnes’s thorough revision of the third part, she asked him to ‘have a further look at Part 2’, but the still-unpublished novelist stood his ground: ‘Stubbornness kicked in. I declared myself content with Part 2; but what I really meant was that I couldn’t face doing any more work on the novel’ (Barnes, 2016a, pp. 2–3).

Although the book was now ready for publication, the sense of imperfection still gnawed at the unconfident writer: ‘I was prepared for failure. I knew the weaknesses of my own novel (we always do)’ (Barnes, 2016a, p. 3). Several years later, he reflected on the feelings that beset him on the publication of his books:

In general, beginning a novel isn’t difficult – at least, compared to finishing a novel; while finishing a novel isn’t difficult – at least, compared to publishing a novel. It’s not so much fear of bad reviews, but something wider and more nugatory: fear of being exposed, fingered, pinned down; fear of getting caught out in some piercing manner. [Barnes, 1989b]

When Metroland was published in 1980, Barnes had been a literary reviewer for seven years and knew how scathing critics could be. To protect himself against a potential exposure, he decided to write in advance ‘the most extravagantly damning review Metroland could possibly receive’ (Barnes, 2016a, p. 3). It was penned by ‘Mack the Knife’ for the Daily Sniveller and mocked the pretensions of young novelists before criticising Metroland for ‘its unoriginality, its disregard of Modernism, its blandness’. While admitting that the author ‘does not write inelegantly’ and ‘occasionally turns a sprightly phrase’, Mack the Knife pointed out that ‘[a] smattering of French cannot conceal the poverty of the author’s imagination, and the novel’s brevity is, alas, no guarantee against tedium’. Barnes’s ‘plan’ was that ‘if any reviewer identified all the faults that Mack had, [he] would give up writing fiction’ (Barnes, 2016a, p. 4). Thankfully, none of the reviews proved as relentless as Mack the Knife’s and most of them were favourable. However, Barnes continued to dread the ‘fear of being exposed’ and repeated the same exercise for his second novel, Before She Met Me (1981), and until 1991, pasted the clippings of all reviews of his books into a volume (1.18).

Even after publication, a book’s imperfections can still unnerve its author, and Barnes had noticed an unfortunate factual mistake in Metroland. When the narrator agonises over his first kiss with his French girlfriend, he gives himself the following advice: ‘Draw her gradually towards you while gazing into her eyes as if you had just been given a copy of the first, suppressed edition of Madame Bovary’ (Barnes, 1980, p. 93). In 2007, Barnes annotated the copy of Metroland he had given his parents upon its publication and wrote next to this passage: ‘Now this is a serious error, given that I went on to write Flaubert’s Parrot. It was the serialisation of M.B. that resulted in prosecution, not the first book edition’ (Barnes, 1980, p. 93). To correct this imperfection, Barnes had the pedantic Flaubertian narrator of Flaubert’s Parrot comment on this passage from an unidentified ‘well-praised novel’ in the chapter devoted to ‘Mistakes in Literature’:

I thought this was quite neatly put, indeed rather amusing. The only trouble is, there’s no such thing as a ‘first, suppressed edition of Madame Bovary’. The novel, as I should have thought was tolerably well known, first appeared serially in the Revue de Paris; then came the prosecution for obscenity; and only after the acquittal was the work published in book form. I expect the young novelist (it seems unfair to give his name) was thinking of the ‘first, suppressed edition’ of Les Fleurs du mal. No doubt he’ll get it right in time for his second edition; if there is one. [Barnes, 1985, p. 78]

This comic self-deprecating passage enabled Barnes to admit to his previous error while mischievously mocking critics’ and readers’ tendency to patronisingly expose such factual mistakes, putting them down to ‘incompetence’ or ‘sloppy literary habits’ (p. 78).

Kazuo Ishiguro, for his part, is often dissatisfied with what he has achieved in his writing and the sense of failure that frequently pervades his novels and their characters is one of which the writer himself is acutely aware: ‘Most of the time, after I finish a book, I’m left with the feeling that I didn’t quite get down what I wanted to. […] I don’t ever feel I’ve written the thing I wanted to write’ (Harvey, 2021). As his first novel, A Pale View of Hills, was about to be published in February 1982, he wrote notes on his impressions which were relentlessly negative: ‘Part I dreary – largely due to narrative tech; – too much dialogue – too many “stage directions” – narration too flat’; ‘Sachiko remains unalive’; ‘Themes don’t interplay’; ‘Too many things crammed in’ (1.2). In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he recalled the ‘niggling sense of dissatisfaction’ (2017, p. 18) that had set in barely a year after the publication of that first novel and, in an interview in 1986, he admitted: ‘The mode is wrong in those scenes of the past. They don’t have the texture of memory’ (Mason, 2008, p. 5).

Another writer might have kept these harsh judgments secret, leaving his doubts to the obscurity of archives, but Ishiguro regularly exposes his authorial imperfections in interviews (and not only about his early work). A form of modesty can be attributed to this self-disparaging attitude but Ishiguro’s honest identification of what he considers as flaws in his published books is what encourages him to strive to perfect his art in his next book. He thus explained that ‘each of his first three books was essentially a rewrite of its predecessor’ (Allardice, 2021) and that he was ‘refining and refining the same novel’ (Hunnewell, 2008, p. 49) in an effort to reach his set goal: ‘You keep doing it until it comes closer and closer to what you want to say each time’ (Allardice, 2021).

One of the recurrent topics in Ishiguro’s published books, which also regularly appears in his unpublished material and in notes and ideas about future work, is the ‘“missed life theme”’ (16.4). Over the years, Ishiguro kept returning to the topic not only because he wished to examine it further but also because he felt some dissatisfaction with the way he had approached it previously. The theme was introduced as early as a secondary scene of his first unpublished novel, To Remember a Summer By (1975–77), when a retired schoolmaster starts writing his first book at the age of sixty but regrets having postponed it until it was too late, aware that he has missed his chance of living the life of a writer (50.4, p. 151). A similar version of that theme is developed in the film script A Profile of Arthur J. Mason (1984), in which a seventy-year-old butler wrote a novel in his youth which is suddenly rediscovered and published to international acclaim, but the success has come too late for the butler who claims that he is content with his life as a servant. Ishiguro commented in 2014: ‘The “missed life” theme is here, also a tying of the butler’s life to post-war upheavals in Britain. But the political themes are still underdeveloped, focusing rather crudely on trad.[itional] class issues rather than on the small man’s relationship to big power, as it was in Remains’ (16.4). The author continued exploring the theme in 1984–85 in an unpublished short story entitled ‘The Patron’, in which an English Lord is beset by the ‘sense of a wasted life’. Feeling that ‘his life thus far has been empty’, he tries to ‘redeem’ it by donating large amounts of money to charity (16.8). Ishiguro wrote in his notes at the time: ‘These are the deep personal themes which made the other two novels – we must stay with them’ (17.1). It is Ishiguro’s sense of not having thoroughly explored the ‘missed life’ theme in his second novel An Artist of the Floating World (1986) which encouraged him to cover the same territory in The Remains of the Day (1989):

[An Artist of the Floating World] struck me as dealing with the theme of the wasted life only from the career perspective. It occurred to me there were other very good ways to waste your life – especially in the personal arena. So Remains was Artist Plus. Stevens wastes both his vocational life and his love life. I set it in England, not Japan, and everyone talked about a huge leap. But it was a remake, or at least, a refinement of the earlier book. [Jordison, 2015]

What a writer considers as incomplete or imperfect in their published work may therefore act as an incentive to refine their craft in later work. While the post-publication awareness of faults comes too late to modify the published work itself (except in the case of revised versions), their identification during the creative process prompts writers to revise and try to ‘perfect’ their texts, although sometimes the sense of imperfection can be so overwhelming that a passage, a chapter or a whole work may be discarded.

In a 1992 essay, Barnes wrote:

There is something so certain, so authoritative in a great painting (novel, piece of music…) that the work almost bullies us into believing that this, and only this, was what the artist initially planned. Even when advised that he or she started off in a completely opposite direction, we half don’t believe the evidence: we persuade ourselves that surreptitiously, subconsciously, they always knew exactly what they were after. [Barnes, 1992, p. 174]

While the drafts of such contemporary British authors as Anita Brookner or Rachel Cusk bear very few marks of revision,3 writers’ archives rarely reveal bright avenues to the published work and more often unveil ‘gardens of forking paths’ (to use Jorge Luis Borges’s image) along which authors experiment with different possibilities, sometimes moving forwards, sometimes drawing back. Genetic criticism has established that the published work stands out ‘against a background, and a series, of potentialities’ (Contat et al., 1996, p. 2) and that ‘we should consider the text as a necessary possibility, as one manifestation of a process which is always virtually present in the background’ (Hay, 1988, p. 75), but ‘the necessity of the work [only] appears in retrospect’ (Ferrer, 2011, p. 54). In Barnes’s A History of the World in 10½ Chapters (1989), the narrator of the chapter entitled ‘Shipwreck’ remarks that when presented with the final result of a work of art, the ‘progress towards it seems irresistible’, the conclusion seems inevitable, but we should not forget the trials and errors and ‘[w]e must try to allow for hazard, for lucky discovery, even for bluff’ (pp. 134–35). In his attempt to find out how Théodore Géricault came to paint The Raft of the Medusa, the narrator therefore examines the preliminary sketches, the discarded ideas and near misses, what he did not paint, very nearly painted and did paint, what he readjusted, raised or lowered, cut, cropped or stretched. Barnes explained that what he himself was aiming at in ‘Shipwreck’ was to ‘reassert the living process – one involving intention, to be sure, but also doubt, chance, underconfidence, overconfidence, false starts, false middles, and so on’ (Barnes, 1992, p. 174). Writers’ archives precisely reveal these imperfect (and necessary) paths, ‘the accident, the forked pen, the list of words that lead nowhere, the scribbling for nothing, the disordered line’ (Grésillon, 2016, p. 28, my translation).

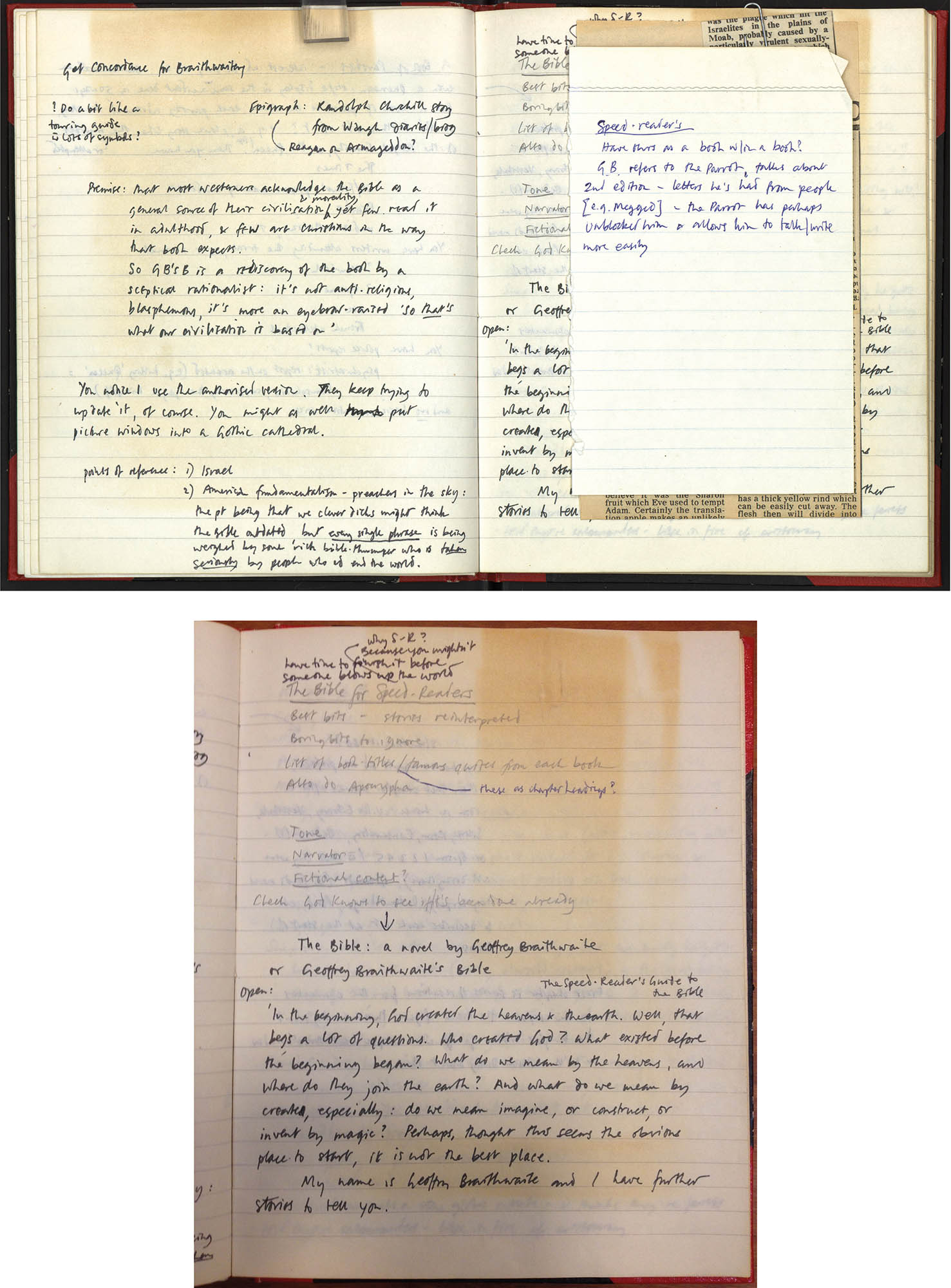

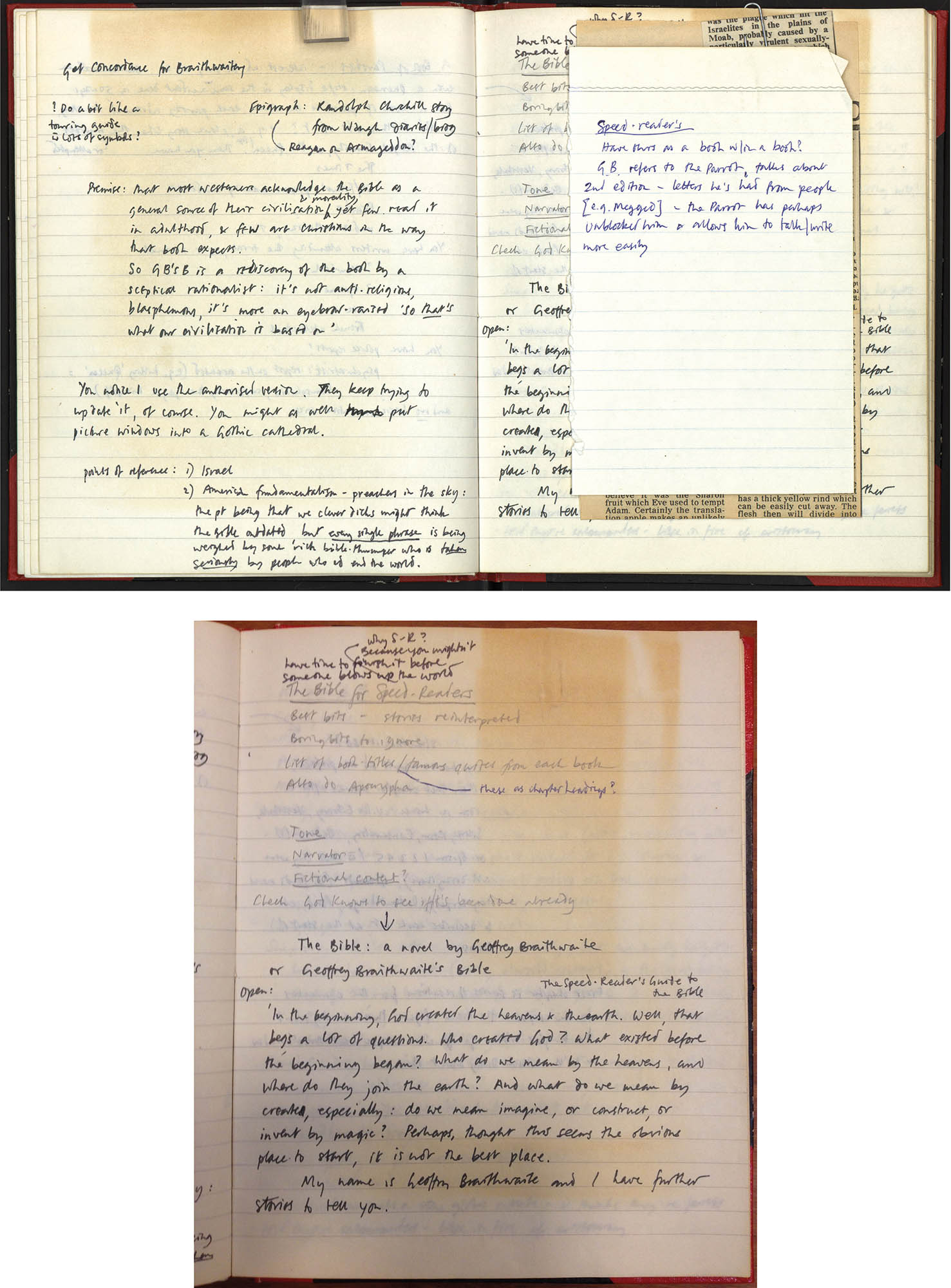

A History of the World in 10½ Chapters is the result of a combination of several ‘forking paths’ and the abandonment of what were deemed imperfect itineraries. Inspired by the success of Flaubert’s Parrot and of its narrator Geoffrey Braithwaite, Barnes thought of writing a book called ‘The Bible: A Novel by Geoffrey Braithwaite’ (or ‘The Bible for Speed-Readers’) whose premise was the following: ‘Most westerners acknowledge the Bible as a general source of their civilisation & morality, yet few read it in adulthood, & few are Christians in the way that book expects. So GB [Geoffrey Braithwaite]’s B[ible] is a rediscovery of the book by a sceptical rationalist: it’s not anti-religious, blasphemous, it’s more an eyebrow-raised “so that’s what our civilisation is based on”’ (1.2; Figure 1). The project is alluded to several times in one of Barnes’s notebooks, which even includes its first sentences (Figure 1), but the writer did not push it any further: ‘It’s another of those things that sounds like a good idea at the time, and then you realize, “Perhaps not”’ (Stuart, 1989, p. 27). The idea was not altogether abandoned, however, as it transmuted itself into the first chapter of A History of the World in 10½ Chapters, a woodworm’s cheeky version of the biblical episodes of the flood and Noah’s Ark.

Source: Barnes, 1971–2000, used by permission of Barnes

Another forking path was related to Géricault’s painting The Raft of the Medusa. The first draft of A History of the World in 10½ Chapters, started on 14 April 1986, was actually entitled The Raft (6.9). Barnes recalls: ‘At one time I had planned a whole book about the Gericault painting, about the seemingly mysterious way in which “catastrophe becomes art”’ (Barnes, 1992, pp. 174–75). The idea was soon slimmed down and reduced to the central chapter of the novel, ‘Shipwreck’, made of two parts, the first relating the catastrophe of the shipwreck of the Medusa in 1816, the second examining the genesis of Géricault’s painting and end result. However, the chapter was not originally shaped as it now stands, as Barnes remembers: ‘As I first saw it, the chapter would be in three sections: the two that survive, plus a third which brought the story up to date (and returned art to life) by describing the rediscovery of the frigate’s wreckage off the Mauretanian [sic] coast in 1981’ (Barnes, 1992, p. 175). He wrote down this original tripartite structure in one of his notebooks (1.2), but the archives do not include the third section: ‘This third part never took off; instead, it atrophied into a couple of lines in a later chapter of the novel’ (Barnes, 1992, p. 175).4 Such changes in the shape of the overall book and in the structure of the individual chapter offer a prime example of the pliability of artistic intention and the flexibility of the creative process, starting with an array of possibilities and marked by the discarding of false trails.

Then, the choice of a given path is no guarantee against imperfections and a writer’s drafts often feature crossed-out words, ‘cancelled passages or textual pentimenti’ (Van Hulle, 2022, p. 127). As noted by Barnes, ‘[w]riting the first draft is usually a great illusion. The first draft makes you think that the telling of this story, whatever it is, is a fairly blithe and easy business. Then you realise you’ve fooled yourself yet again. Then the work, the real writing starts’ (Guignery, 2013, p. 22). The numerous corrections on Barnes’s manuscripts and typescripts attest how carefully and relentlessly he hones his style and strives to perfect his text. As he points out, ‘substantial things can be changed… even quite late in the day’ – be it the names of characters (as in The Sense of an Ending), the use of tenses (as in Arthur & George) or part of the structure (as in Flaubert’s Parrot and A History of the World in 10½ Chapters) – and ‘the book can always be improved’ (Guppy, 2009, p. 81). When editor Calder asked Barnes for substantial revisions to the third part of Metroland, he complied with her requests, deleting about twenty-two pages out of the original fifty-four and adding around nine.5 In a letter to Calder, he meticulously explained his changes in emphasis, structure and character to try and ‘make Part Three less relentless in its parallels to Part One, less crudely reflective’, less of a ‘contented solipsistic elegy’ for the adult narrator Chris as he happily returns to live in the middle-class suburb of Metroland he used to sneer at as a teenager (10.5). His revisions were meant to make ‘Christopher’s character-change plausible’: ‘The first time I did it, I made him amazingly complacent and changed, and it was just wrong for that kind of time-structure. He couldn’t have sunk into as deep a rut as I made him fall into’ (Hayman, 2009, p. 4).

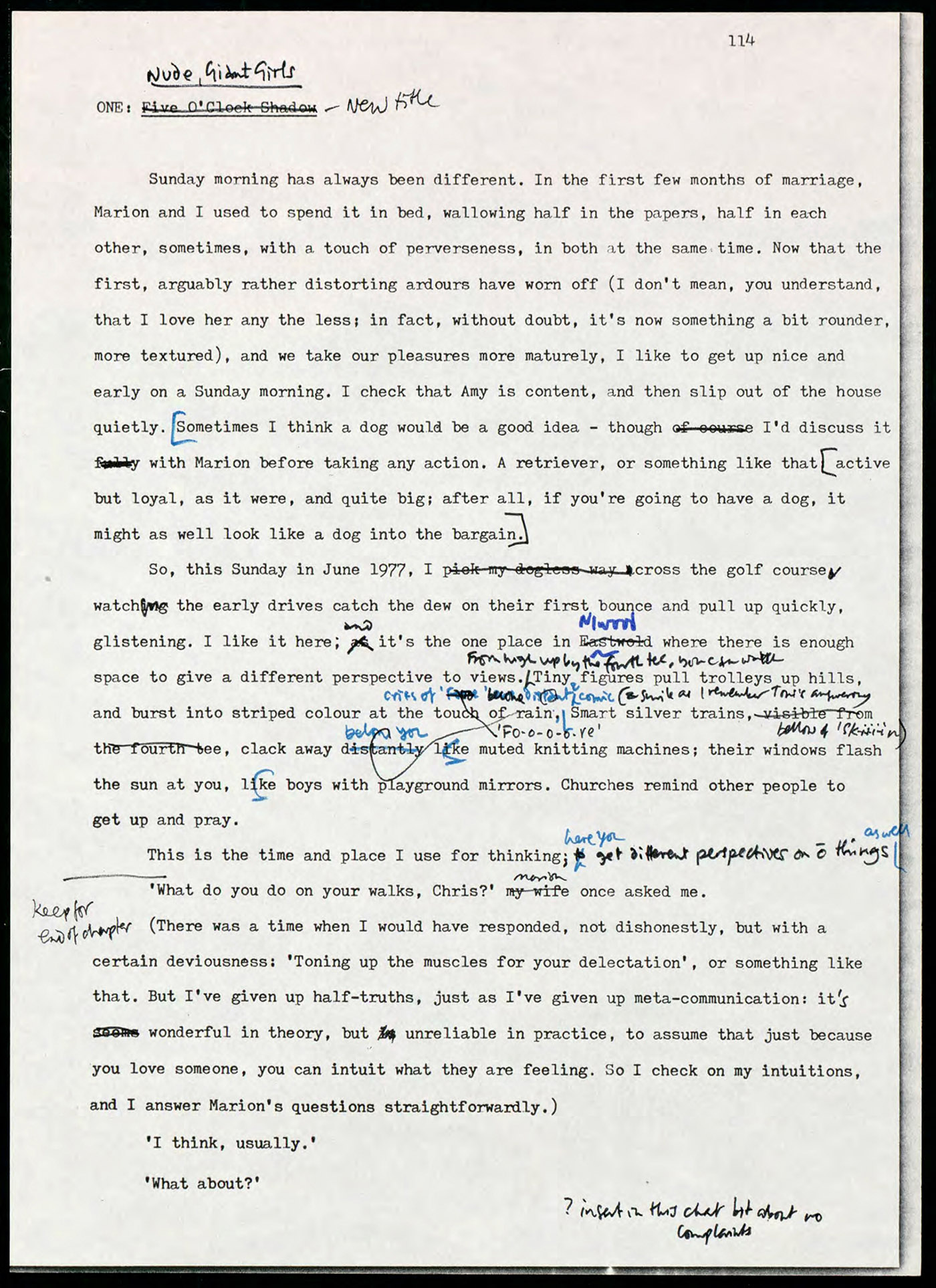

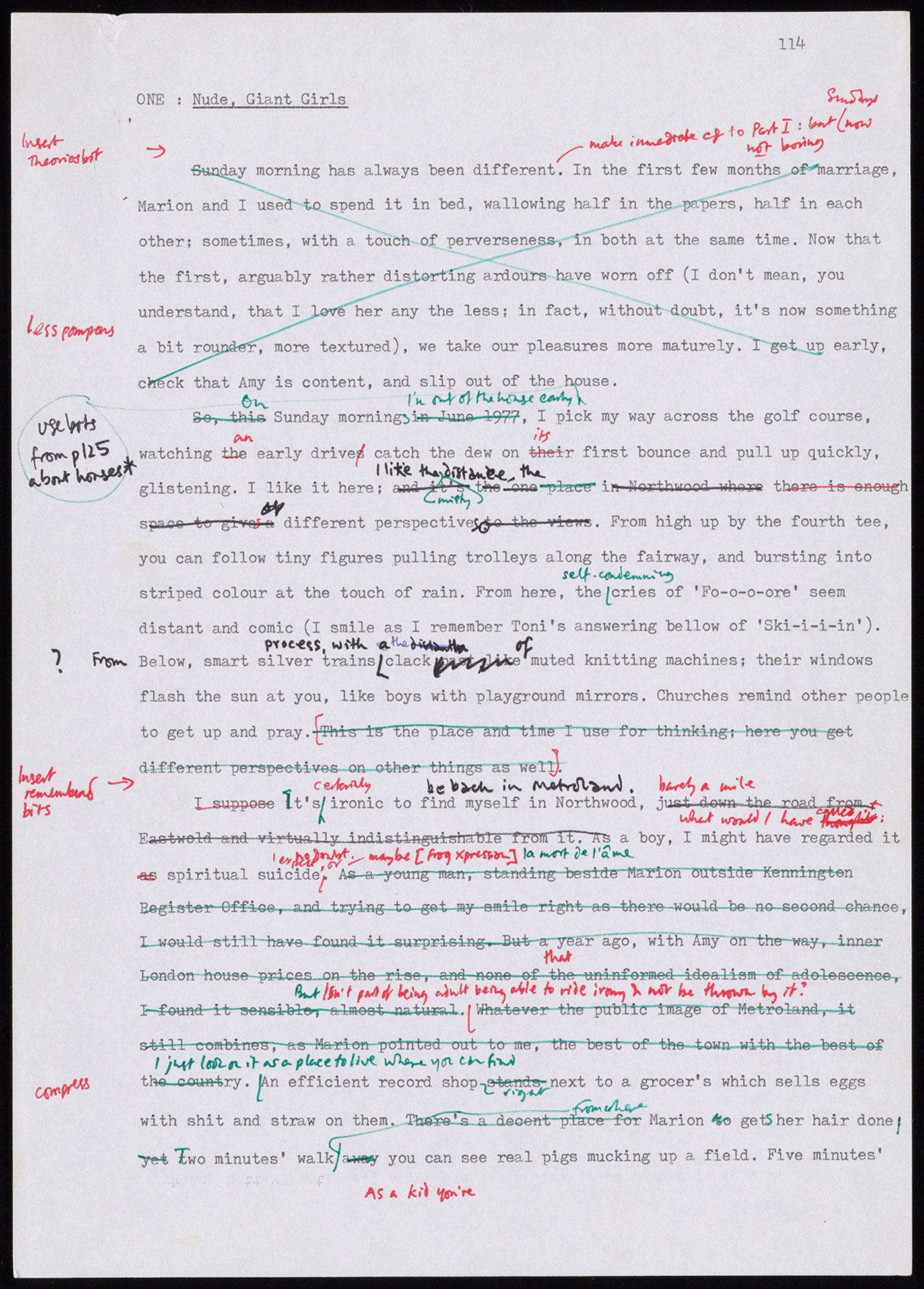

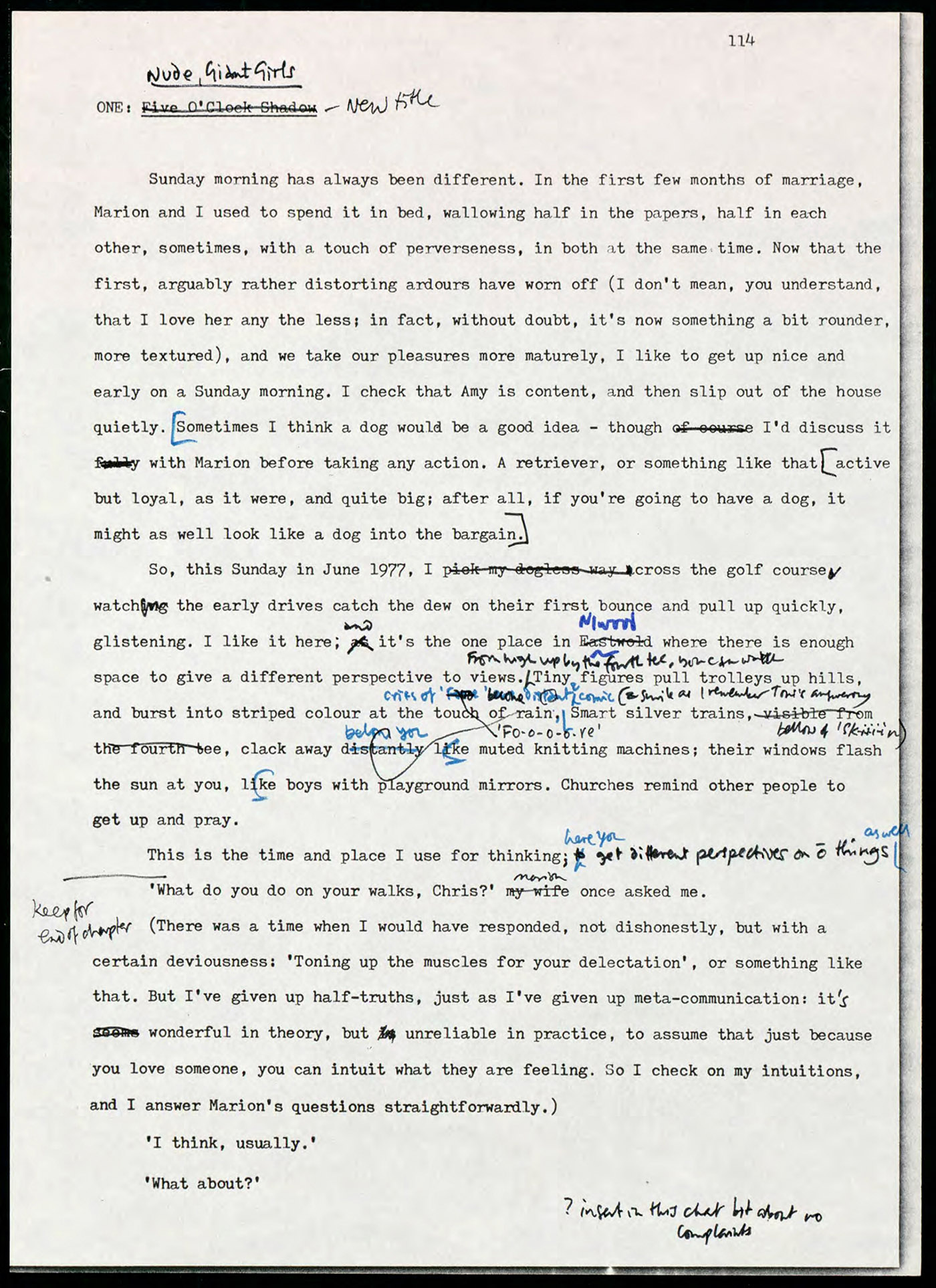

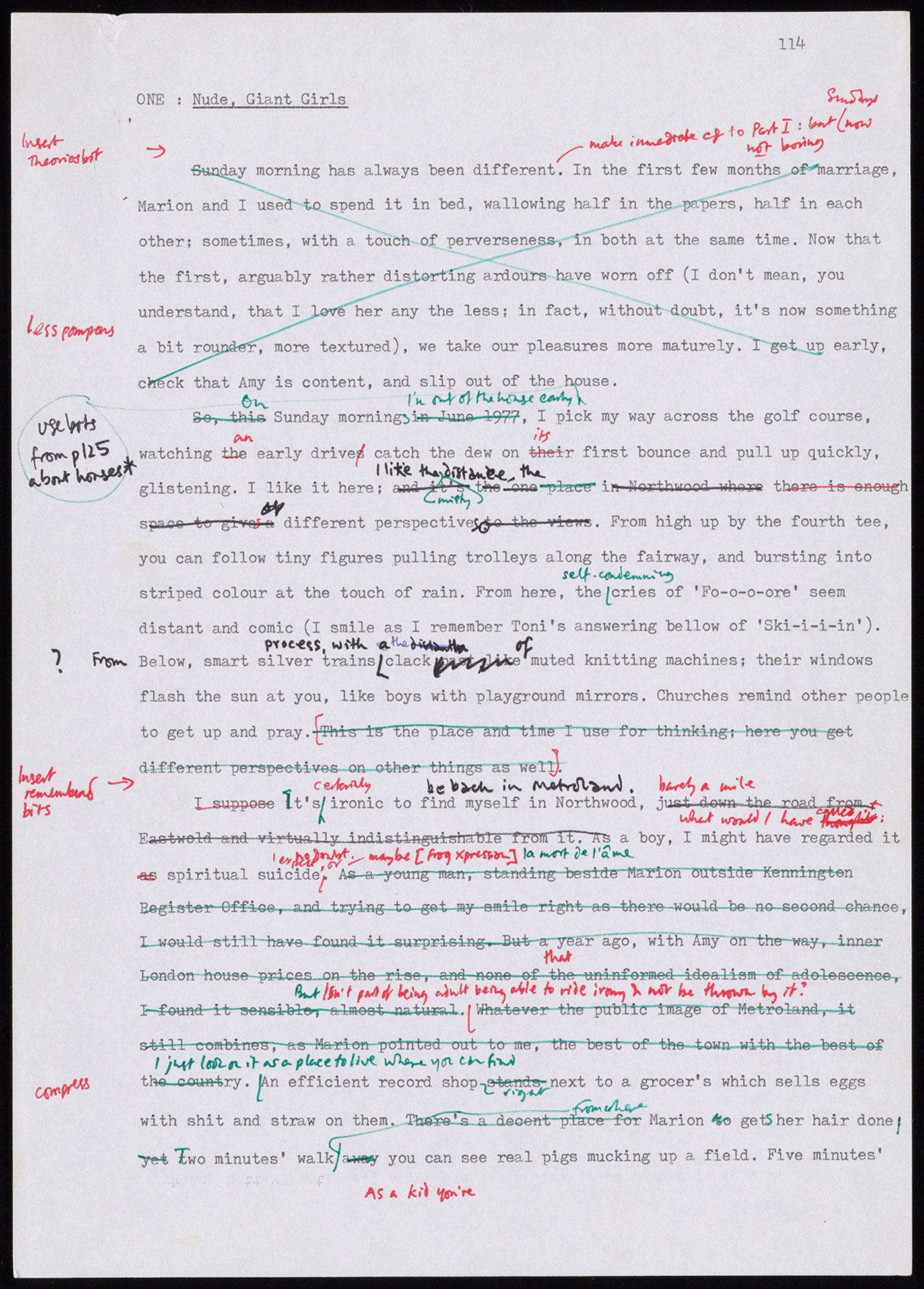

At the microlevel, the first chapter of Part Three was thoroughly revised as shown by a comparison between an early and a later draft and the published version of the first page. The heavily annotated pages of the early and later drafts both contain comments and corrections in three different ink colours (light blue, dark blue and black for the former; black, green and red for the latter), which probably reflect successive layers of revisions (Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Source: Barnes, 1971–2000, used by permission of Barnes

Source: Barnes, 1971–2000, used by permission of Barnes

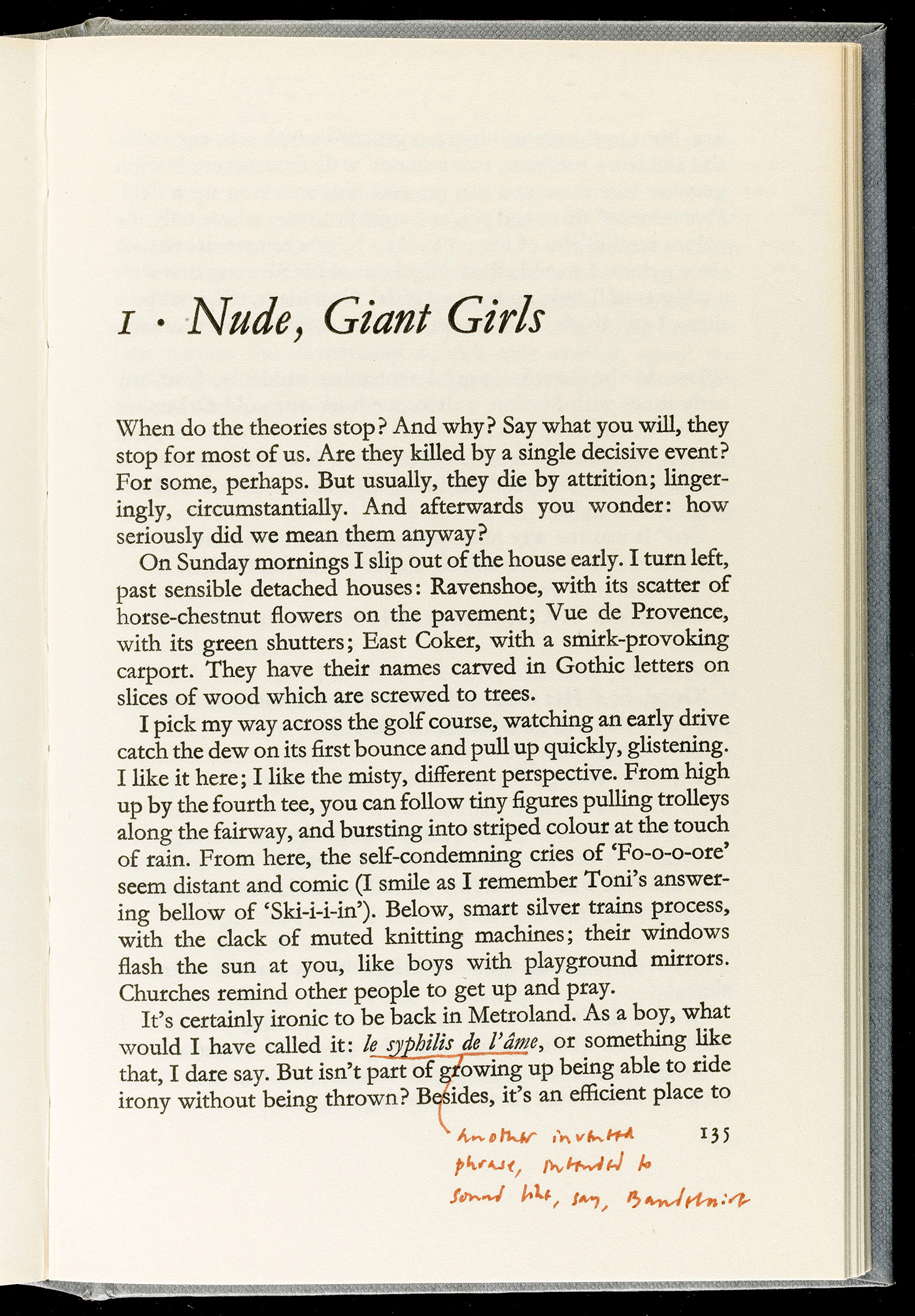

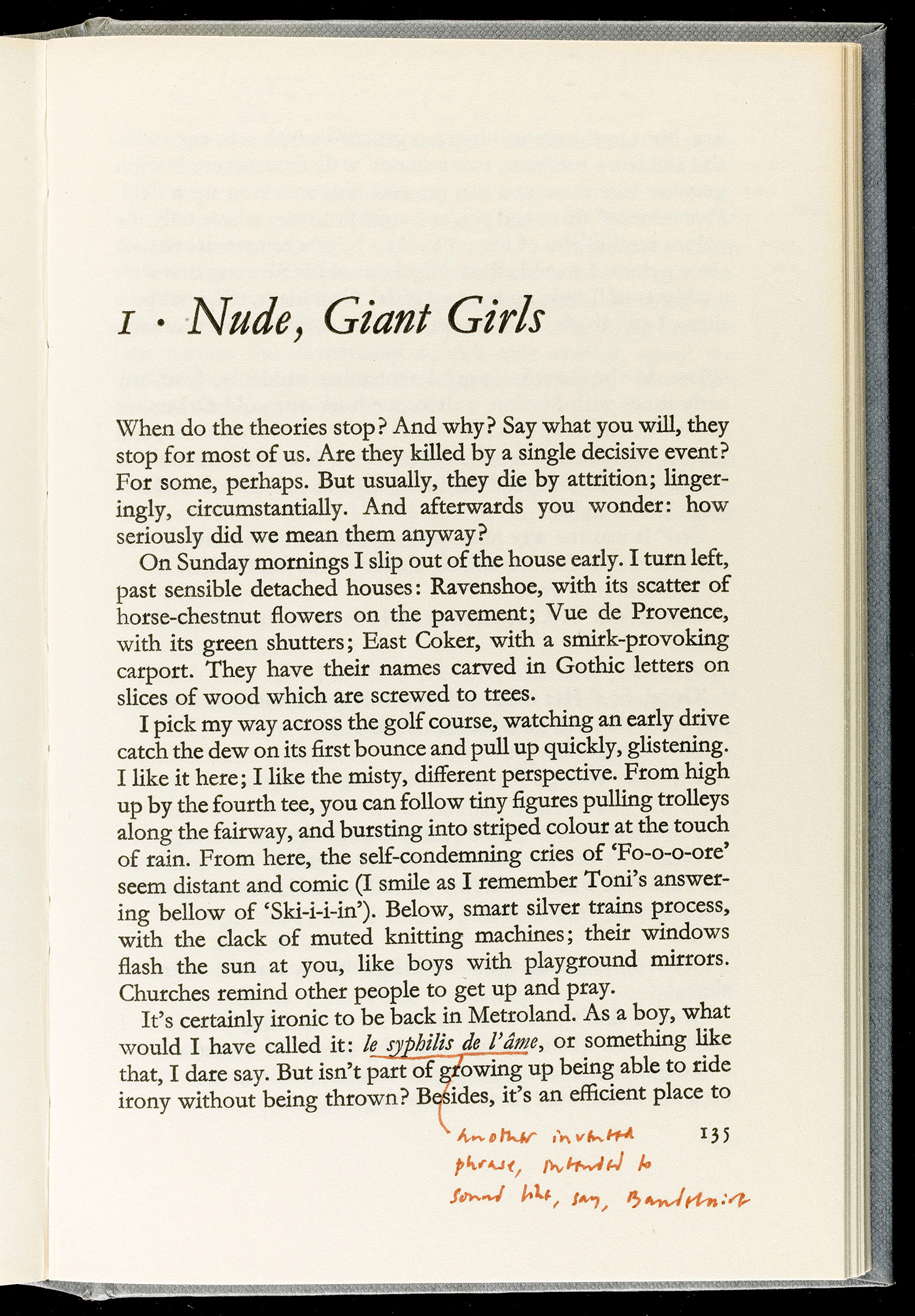

Source: Barnes, 1980, p. 135; PML 194959, New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Alyce Toonk, 2013

The original title, ‘Five O’Clock Shadow’ (a reference to the stubble Chris never gets at the end of the day, which he interprets as a sign that he might not be ‘responsible’ enough, 10.6, p. 117), was crossed out because the passage where the expression appeared was deleted. The more cryptic title which replaced the original one (‘Nude, Giant Girls’) is an allusion to the pylons Chris and his family used to drive past when he was a child. The narrator would then whisper to his brother: ‘Look, nude, giant girls’ (Barnes, 1980, p. 136), an unidentified reference to lines from the 1933 poem ‘The Pylons’ by Stephen Spender.6 In the later draft, although Barnes wrote after the first sentence ‘make immediate cf to Part I: but Sundays now not boring’, the first paragraph was crossed out (with the injunction to make it ‘less pompous’) as he specifically wanted to tone down the parallels with the first part and make Chris less complacent.

Several passages originally placed elsewhere were to be integrated in this incipit, as indicated by the handwritten imperatives in the margin: ‘Insert theories bit’ for the first paragraph, ‘Use bits from p. 125 about houses’ for the second paragraph – these passages were indeed moved to that opening page – and ‘Insert remembered bits’ before the third paragraph, though this passage was shifted to a later point in the chapter (p. 138). On the other hand, the references to Chris’s marriage and his love for his wife Marion were discarded. These changes were emblematic of Barnes’s effort to make his male character ‘sharper, clearer, more self-aware’ and to put across ‘not that he’s become a smug bourgeois, etc. (which he hasn’t), but that he’s semi-gracefully, if sometimes ironically, submitting to the onset of happiness, love, materialism’ (10.5). Chris’s pedantic habit of using foreign words, which he developed during his youth, was nevertheless retained in his metaphorical description of his return to Metroland: to the early draft’s original sentence (‘As a boy, I might have regarded it as spiritual suicide’) was added in red pen ‘or maybe [frog xpression]’, and then in green pen ‘la mort de l’âme’ (Figure 3), but the published version includes the phrase ‘le syphilis de l’âme’ (Figure 4). In his annotated copy of Metroland, Barnes commented on the choice of this expression (used with the wrong article, possibly as a way to mock Chris’s pedantry): ‘another invented phrase, intended to sound like, say, Baudelaire’ (Figure 4).

The garden of forking paths and myriad possibilities, which may contain ‘the trompe-l’oeil cul-de-sac’ (Barnes, 1985, p. 115), false trails and imperfect itineraries, can also include wrong turns in terms of style and narrative voice. As Barnes remarked: ‘You start off with different possible tonalities and the right one only gradually comes into play’ (Freeman, 2016). He recalls that when he started writing his twelfth novel about the composer Dmitri Shostakovich, The Noise of Time (2016), he penned it in the first person but had to stop after four pages: ‘I didn’t know why it wasn’t working, it just wasn’t working at all, and I had just done it in the wrong person. I went back to it about nine months later, and started in the third person’ (Freeman, 2016). The original incipit of the novel started with a line by Gustave Flaubert about the absence of heroes and monsters in modern life, which implied that they should not appear in literature either. Barnes recalls: ‘And so the book began with a riff that the monsters had come back, and the monsters had killed all the heroes, so we live in a world that is monster full, and hero free. But I eventually scrapped it because it was too declamatory, it was too un-novelistic’ (Freeman, 2016). Such examples confirm that imperfections also plague mature novelists (‘with each new book, you make new mistakes’, Barnes declared in Freeman, 2016), although in the case of Barnes, the typescripts of his more recent work are less heavily revised than earlier on in his career: ‘I know more what I’m doing, so there are fewer false trails that have to be abandoned’ (Bhattacharya, 2013, p. 41).

Ishiguro’s archives reveal that he often abandons false trails after many months of exploring them and sometimes after having completed a story or a book. His archives thus contain several completed but unpublished stories and novels. Most of them are juvenilia dating from the 1970s and may therefore be considered as part of his training as an apprentice writer. In addition to four short stories dating from 1975, he completed two novels between 1974 and 1978, To Remember a Summer By and Sylvie, which depict ‘the anxieties and uncertainties of young middle-class people in late-70s Britain’ (51.1), but he only submitted the first one to a publisher (who turned it down). In a letter to a friend dating from April 1976, he wrote: ‘For my next novel, I will make a simple rule to prevent it growing as uneventful as my present project: someone will die on every seventh page’ (60.3). And yet, his second unpublished novel is written in the same vein. In a notebook dating from 1978–79, he reflected: ‘I look back on Sylvie & Summer & am struck by the uneventfulness of the stories. Why didn’t I get bored writing them, I ask?’ (62.8). In 2014, he approached the same conclusion: ‘What is striking – perhaps most interesting – is how content I was to keep proceeding with such a determinedly uneventful narrative. It would be tempting to claim the lack of drama was wilful, part of some artistic ploy, but I think it displays a simple failure to imagine beyond the obvious’ (50.1).

Aware of this imperfection in his early novels, Ishiguro attempted to introduce more drama and suspense in his later work. His ‘3rd novel’ (51.1), written in 1978–79 and uncompleted, while still featuring a group of idle middle-class young people in Britain, includes a ghostly dimension as the protagonist’s dead ancestor haunts the country house where Karen is staying with friends for a few days. Ishiguro’s imagining of a single mother killing her own child by drowning her in the bath and then hanging her from a tree in the garden (elements which find echoes in his first published novel A Pale View of Hills, 1982) evidenced a drastic change of direction in his writing, which may have been a response to his fear of being boring. It was the same anxiety which led him, in 1979, when he joined the one-year postgraduate Creative Writing Programme at the University of East Anglia (UEA), to write such short stories as ‘Waiting for J’ and ‘Getting Poisoned’ (published in Faber’s Introduction 7: Stories by New Writers in 1981). Both stories are marked by intense sadomasochistic violence and an uncanny and absurdist dimension which reveal an interest in ‘psychological trauma’ (Shaffer, 2009, p. 19). In notes written on 30 September 1983, Ishiguro remembers that when Malcolm Bradbury read ‘Waiting for J’, he perceived that the young writer would soon be confronted with a ‘conflict’ between his ‘worry about “being boring”’ which led him to ‘bring in plots – grab for irrelevant, distracting opportunities for supernatural sub-plots, eerie McEwanesque effects’7 and a contrary wish to write about ‘“boring” things’ (1.4), what James Wood later described as ‘the dizzying dullness’ of novels which seem to ‘welcome cliché, platitude, episodes as bland as milk’ (2015, p. 92).

Ishiguro was constantly aware of this nagging conflict in his writing, which re-emerged in A Pale View of Hills. In early drafts of the novel, Ishiguro included several scenes which underline the sense of threat caused by the future mother Etsuko to Mariko, the daughter of her next-door neighbour in Nagasaki. Although Ishiguro deleted several of these passages, in his ‘Thoughts on A Pale View of Hills on publication’ in January 1982, he wrote that the ‘suicide/threat to Mariko theme’ was ‘prompted as a way of making [the] book more readable – i.e. have a “thriller” run alongside real story’, but added that ‘it can be dangerous to fall into this temptation – perhaps in future be more confident. After all, it’s non-thriller bits that work best!’ (1.2). For his second novel An Artist of the Floating World (1986), Ishiguro was determined to resolve this conflict and rigorously and courageously stick to his central vision even if it entailed having ‘pages going by with “nothing happening”’: ‘I must not bring in elements through a nervousness about readability’ (1.4).

While A Pale View of Hills and An Artist of the Floating World are marked by a generally subdued tone in which the trauma of the atomic bomb is kept in the background, Ishiguro’s uncompleted novel dating from the early to mid‑1980s, Flight from Nagasaki (49.7), directly addresses the aftermath of the bomb, but the writer judged his attempt imperfect. The novel features two young girls who, after the bombing of Nagasaki, are sent by their parents to a village in the mountains to make sure they are away from the city during the American occupation. The uncompleted first draft of four chapters and forty-one pages, partly based on his mother’s ‘memories of the Nagasaki bombing’ (49.7), is characterised by blunt descriptions of the devastating effects of the bomb on bodies and psyches (especially in chapters one and four), and the style thereby greatly differs from the indirect mode of Ishiguro’s first three novels. For instance, the narrator describes a funeral pyre where a woman is cremating the body of a man and the gruesome detail of ‘two bare feet protruding’ catches her attention: ‘I guessed immediately that she had not been able to hoist the body onto the pile high enough on her own; I watched as the young woman tried to prod with a wooden beam at the pile, as if in hope that the feet would somehow disappear, but they remained stubbornly thrust out to the world’ (49.7, p. 7). The detail of the protruding feet returns to haunt the narrator after she has found refuge in the mountains.

After rereading the first chapters in September 1983, Ishiguro wrote:

The opening chapter is riveting [sic], but perhaps for the wrong reasons, and then there is the problem of what happens in the wake of that; The thing does slow down considerably, and at times we start to get a good flavour of village life, but perhaps the bomb thing does make it rather capitalising on the echoes... certainly, there are quite nice moments throughout, and the language is surprisingly fluent considering its [sic] first draft, but there’s something wrong about the pacing of it… it certainly isn’t as impressive by the time you get to chapter two and three as during opening chapter, and this is a rather predictable failure... [49.7]

It might be because of that ‘predictable failure’ that Ishiguro abandoned the project. Such a decision on the part of the writer is not unusual as, in addition to the juvenilia, his archives contain several drafts of stories, as well as outlines for films or book chapters, which he did not bring to completion or discarded from the final draft despite having spent a considerable amount of time and work on them.8 The narrator of Flaubert’s Parrot stated that ‘an idea isn’t always abandoned because it fails some quality-control test’ (Barnes, 1985, p. 115), but Ishiguro’s frequent ‘scrapping’ of projects and completed chapters or texts is usually caused by an overwhelming sense of imperfection.

In Flaubert’s Parrot, the narrator reflects on style and comments: ‘The correct word, the true phrase, the perfect sentence are always “out there” somewhere; the writer’s task is to locate them by whatever means he can’ (Barnes, 1985, p. 88). The creative practices of Barnes, Ishiguro and Okri reveal how relentless these writers are in their quest for the perfect word, phrase or sentence, but also the correct tone, structure, characterisation and narrative technique. When Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day was published, Barnes praised it for its subtle punctiliousness, careful execution, ‘narrative sophistication and flawless control of tone’ (1989a, p. 18). And yet, in an interview in 2008, Ishiguro recalled Terence Rafferty’s piece in The New Yorker which ‘appeared to be a glowing review right up until the end. Then it said: the trouble with this is that everything works like clockwork’ (Hunnewell, 2008, p. 48). The reviewer’s admiration for ‘the poise and formal beauty of the writer’s performance’, the ‘practiced craft’ and ‘technical mastery’ of ‘this irreproachably composed work of fiction’ was set against the sense ‘that the writer, no less than his protagonist, is shackled by his own expertise, by a helpless obsession with living up to standards’ (Rafferty, 1990, p. 104). The critic was thereby finding fault with the novel for being too neat, too controlled – in other words, too perfect. Ishiguro himself had confided his doubts in an interview with Graham Swift in 1989: ‘I sometimes wonder, should books be so neat, well-formed? Is it praise to say that a book is beautifully structured? Is it a criticism to say that bits of the book don’t hang together?’. He felt it was time for him to explore ‘the messy, chaotic, undisciplined side’ (Swift, 2008, p. 41), which he did in The Unconsoled, a book which, according to Wood, ‘invented its own category of badness’ (2000, p. 44). While this sounds like a severe judgment on Ishiguro’s fourth novel, it may reflect what the writer himself was specifically testing: a form of imperfection that would most perfectly reflect the indiscipline he was looking for. When it comes to artistic creation, the concepts of perfection and imperfection are destined to remain highly subjective, and if manuscripts are to be considered as ‘evidence of […] failure as a driving force of artistic invention’ (Rosignoli, 2016), their imperfect itineraries and faulty textures are worth exploring.

Source: Barnes, 1971–2000, used by permission of Barnes

Source: Barnes, 1971–2000, used by permission of Barnes

Source: Barnes, 1971–2000, used by permission of Barnes

Source: Barnes, 1980, p. 135; PML 194959, New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Alyce Toonk, 2013