Pip and Billy as Fluid Texts

The title of our collection – Imperfect Itineraries – acknowledges the fortuitousness of the creative process. In writing, our plans never proceed as perfectly as planned. The itinerary you had imagined may take unexpected turns, landing you in unanticipated territory. Perhaps it would be better to say that such unpredictable turns will always occur, that the initial destination is never fully reached, that the act of writing is inherently incomplete.

If writing is fundamentally revisional, and all itineraries necessarily provisional, the adjective in ‘imperfect itineraries’ may be apt, but it is also a knowing redundancy. It assumes a standard of ‘perfection’ that a writer might wish for in drafting a written work – that the writing will go swiftly, that it will ‘write itself’ – but the writer also knows from experience that perfection is a phantom of desire. The working draft manuscripts I have studied invariably show that writing is a messy, searching, adventitious affair, often experimental, and necessarily ‘imperfect’, so that a ‘perfect itinerary’ may be at best a dream perpetually deferred, until a work is surrendered to editors and publishers.

A word more attuned to the pragmatics of composition is ‘essaying’, an English word borrowed from the French ‘essayer’, meaning ‘to try’. Here, the assumption is that the writing process is an ‘attempt’ at finding words that might portray a character, describe a scene, capture a moment, or convey an idea. Herman Melville explains the dilemma of writing throughout Moby-Dick. In ‘The Prairie’ (Chapter 79), his principal essayist Ishmael tries to grasp the meaning embedded in the whale’s featureless face, saying at first ‘I try all things; I achieve what I can’.1 He ‘essays’ the whale in order to grasp at this ‘ungraspable phantom of life’, but admits he cannot (Chapter 1). Granted, a writer’s revisions are invariably motivated by a desire to land, finally it is hoped, upon some mot juste – to ‘achieve’ and not just aim for the perfect word – but we also know that writers continue to revise their texts and themselves, even after publication, so that the struggle for grabbing the right word never really ends. The struggle is simply interrupted by deadlines.

The regular course of revision – a writer’s ‘essaying’ – is necessarily unplanned and seemingly imperfect, and yet its itineraries follow their own logic of invention, digression, discovery, and return. We may discern this logic, discuss it, and derive arguments about the meaning of revision but only if we have concrete evidence of the versions and revision steps. Tracking the journey of a work in revision – what I call a ‘fluid text’ – requires us to sequence acts of revision as they unfold through multiple versions and to narrate the logical hows and whys of that adventitious itinerary in the context of the formal features of the work itself, the desires of the writer, and the demands of the writer’s culture.2 Only when a written work’s versions and revisions are put before us concretely might we begin to gauge the distance between writerly aspiration and social surrender – between ‘try’ and ‘achieve what I can’ – and thereby ‘read’ the creative and cultural energies that impel textual fluidity. However, conveying revisions concretely and tracking their itineraries are monumental tasks. Concluding his fruitless search for meaning in the whale’s face and brow, Ishmael speaks as well to the problem of textual fluidity: ‘But there is no Champollion to decipher the Egypt of every man’s and every being’s face. […] I but put that brow before you. Read it if you can’ (Chapter 79).

The problem of reading revision is much like trying to read a whale; its features and energies are remote, concealed and ungraspable. Because the phenomenon of textual evolution is invisible, we must edit the evidence of the revision text into visibility. That is, the revision text of a work exists between the versions of the work, and the versions have to be edited in tandem for us to ‘see’ the distances between them before we can articulate the ‘unseen’ texts of revision in ‘revision narratives’ and before we can ‘read’ the meaning of their evolution critically and culturally. More broadly speaking, fluid-text editing helps us discern different kinds of versions, and a written work may encompass a combination of authorial, editorial, and adaptive revision.3 That is, the full scope of any given fluid text as it evolves from one version to the next will involve not only the originating writer writing but also editors editing and adaptors adapting. Moreover, within any single version we will also find writers editing (even censoring) themselves and adapting the texts of other works into their own, with and without attribution.

These kinds of versions in Melville’s fluid texts are not ‘imperfect’ in their stages of development; rather, they are aspirational, experimental, self-probing, perpetually tentative, and radically incomplete. This tentativeness in Melville’s writing – the exploratory unfoldings and uncertain contingencies of his creativity – not only emulates the mind’s never-complete essaying of reality but also contributes to a broader aesthetics of incompletion that we find throughout his works and especially in his final prose-and-poem work Billy Budd.

For Melville, incompletion was a condition of textuality, self, and art. In a June 1851 letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, he compared his writing process to the peeling of the layers of a flower bulb. He said he was ‘unfolding within [himself]’ and that, in writing Moby-Dick, he was coming ‘to the inmost leaf of the bulb’. He further complained: ‘What I feel most moved to write, that is banned, – it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the other way I cannot. So the product is a final hash, and all my books are botches’ (1993, p. 193; his emphasis). But as he was finishing Moby-Dick, he was already writing his next novel Pierre and lamenting, again to Hawthorne, a few months later: ‘Lord, when shall we be done growing?’. And, again a few lines later, he repeated himself: ‘Lord, when shall we be done changing?’ (p. 213).

Melville’s self-deprecating rant strikes at the heart of his dilemma as a writer. He can only write from the self, but the market demands that he write its ‘other’ way. Yet even when he panders to readers, his publishers censor him. One way, the other, and both, his works become ‘botches’. And yet he persists during the summer and fall of 1851 to revise and proof Moby-Dick while beginning Pierre. He had not reached the ‘inmost leaf’ of his creative being, and his seriocomic lament about his botches reads, in retrospect, as a mantra for creativity, revision, and incompletion: he was not done ‘growing’, not done ‘changing’. Somehow the incestuous urban gothic Pierre was sprouting even as his essayistic Shakespearean whaling tale was reaching its tragic end, and what Melville divulged to Hawthorne about his never-complete condition as a writer was as much inherent in his structuring of Moby-Dick.

In Chapter 32, titled ‘Cetology’ – the first and longest of Ishmael’s meditations on whales – Melville classifies whales not scientifically but bibliographically, sorting whales not by anatomy but by size, like books: folio, octavo, duodecimo. His system is pointedly unsystematic: an arbitrary imposition of writing and publishing practices on nature, designed to fall apart, which it does as Ishmael concludes the comic chapter. He declares his bookish classification of whales to be perpetually ‘unfinished’, like ‘the great Cathedral of Cologne’ with its cranes still standing atop its ‘uncompleted tower’. And he ends the chapter with another version of his letter to Hawthorne: ‘God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught – nay, but the draught of a draught’. But here Melville’s former lament about the exhaustion of ‘growing’ and ‘changing’ has itself morphed into a chest-thumping credo in which completion is not simply unachievable but undesirable and that a ‘whole book’ is nothing but one ‘draught’ or version after another. In a later chapter, about erroneous depictions of whales, Ishmael underscores the impossibility of representation, let alone classification: ‘the great Leviathan’, he concludes, ‘is that one creature in the world which must remain unpainted to the last’ (Chapter 55).

These Ishmaelean observations from 1851 are early articulations of Melville’s aesthetics of incompletion. Forty years later, as he was nearing death and bringing Billy Budd to an end, if not completion, Melville’s unnamed narrator replays the architectural imagery of the Cologne Cathedral in Moby-Dick to explain the inherent incompleteness of representation: ‘The symmetry of form attainable in pure fiction can not so readily be achieved in a narration essentially having less to do with fable than with fact. Truth uncompromisingly told will always have its ragged edges; hence the conclusion of such a narration is apt to be less finished than an architectural finial’ (2019, Chapter 28). Rather than attempting to classify whales in a way that is doomed to fail, or expecting great edifices ever to be ‘done’, Melville focuses here on what elsewhere he called ‘the great Art of Telling the Truth’ (1987, p. 244), which in the particular instance of Billy Budd means giving readers facts not fables about human desire, more specifically the officer Claggart’s secret longing for the youthful beauty of his inferior, the sailor Billy. The narrator wants to reach the source of Claggart’s repressed anger and self-loathing to determine the ‘mystery of iniquity’ within him, but he has only fragments of rumour and insinuations to go on, and he withholds as much from readers as he withholds from himself. Or, at least, that is how Melville’s self-consciously conscientious narrator has us read the dilemma of necessary incompletion in any kind of narration: fiction, history, biography. To compound this condition of unknowing, Melville added to Billy Budd, in a late stage of revision, three fragmentary concluding chapters, offering new facts, falsifications, and myths, each a finishing touch or ‘finial’ that makes the novella seem all the more ‘ragged’.

Melville’s aesthetics of incompletion is no doubt rooted in his own sense of his perpetually unfolding, always growing and changing, identity. But to presume that identity alone ordains the shape of art – that a ragged life will render ragged narratives – is a disservice to biographical critical thinking, especially if such a presumption becomes a Procrustean conclusion that precludes further discussion. To be sure, as an unfolding of one’s evolving self, writing may be commensurately incomplete. To be sure, editors and publishers may conspire to revise and expurgate one’s book into a botch. To be sure, language can only approach the thing it attempts to represent, and therefore can only be ‘unfinished to the last’ and ‘less finished’ than what convention might lead us to expect. Even so, Melville’s evolutions as a writer exhibit a remarkable degree of narratorial experimentation, and he deployed his aesthetics of incompletion through differing rhetorical strategies yielding different effects. Nor should we assume that Melville’s final effort – the purposely ragged Billy Budd – is a fixed urn for Melville’s life-long experimentation. Melville died five months after he claims, in his manuscript, that he had finished the novella. However, the surviving manuscript is a collage of partial and full leaves inscribed in pencil as well as ink and not a fair copy ready for a publisher, copy editor, and printer. Had Melville lived longer, he could have continued polishing the existing thirty chapters and poem; or he could have shortened his text into a tale or lengthened it into a novel. We cannot know. Billy Budd is a fluid text frozen by the accident of death, and a biography of Billy Budd as a fluid text must necessarily be incomplete.

Such a biography would not proceed from the presumption of the author’s organic disposition for incompletion but with the assumption that, as an artist, Melville was weaving into his ‘truth uncompromisingly told’ certain patterns of revisions that graphically embody artful acts of incompletion. The life suffusing these ragged versions – inscribed in pencil and ink on leaves and fragments – represents the energy Melville spent in making them. The biographer’s aim is to narrate this expended energy. In his revisions, we feel Melville’s resistance to a recalcitrant culture expecting easy explanations, to a society reluctant to find beauty in the inner lives of the dispossessed, to a language inadequate to the expression of forbidden desire, and even his resistance to his own identity as he struggles to articulate his evolving aesthetics of incompletion.

To clarify how this kind of biographical approach to revision might work, I want to look at two widely separated episodes in Melville’s growth as a ‘truth-telling’ artist: one from Moby-Dick; the other from Billy Budd. Both instances have to do with what I call Melville’s ‘black consciousness’, that is, his empathy for shipmates dispossessed because of race, ethnicity, and economy.4 Each episode demonstrates how, in one way or another, memory unfolds differently through the writing process.

Revisions are textual and biographical. The changing of a word records a writer’s most intimate moment: a change of mind. A shift in phrasing might trigger memories that take flight into inventions of new language that require retrospective erasures of previous wordings and/or prospective ventures into new arguments, rhetorical effects, and versions. These kinds of changes are graphically rendered in the Billy Budd manuscript. But manuscripts for Moby-Dick no longer exist. Even so, a comparison of internal textual inconsistencies in Moby-Dick and biographical information drawn from external documents can reveal an even more fundamental intimacy of creation, that is, Melville’s transformation of a life event into fiction. I am speaking of Melville’s development of the Black cabin boy Pip.

While editing Longman’s fluid-text edition of Moby-Dick, I was drawn to inconsistencies, familiar to readers, involving Pip’s birthplace. Equally intriguing is the fictive ‘fact’ of Pip’s very presence on board Ahab’s ship. Historically, whaling ships did not employ cabin boys. And yet the fictional Pequod has two: the white steward Dough-Boy and Black Pip. In adapting the Longman print text for the Melville Electronic Library’s digital edition of Moby-Dick, we were able to offer a fuller textual analysis.5 Initially, Pip and Dough-Boy are paired comic figures, a sort of racial diptych: ‘In outer aspect’, Ishmael explains, ‘Pip and Dough-Boy made a match, like a black pony and a white one […] driven in one eccentric span’ (Chapter 93). But at some time in the making of Moby-Dick, evident only in the last third of the novel, Dough-Boy disappears and Pip takes centre stage beside Ahab.

Readers of Moby-Dick are familiar with Pip’s fate. In ‘The Castaway’ (Chapter 93), Ishmael praises the cabin boy for the ‘brilliancy’ of his blackness and his ‘gloomy-jolly’ personality. Always stationed on board ship, Pip has never encountered a whale, but that all changes when the inexperienced lad is made to replace an injured oarsman in the hunt. When a harpooned whale takes off with Pip’s whaleboat in tow, the frightened cabin boy ‘leaps from the boat’ and is tangled in whale lines. Pip is saved from strangulation when Stubb cuts him loose. Warned to stick to the boat, he is bumped off once again, but this time is left behind and nearly drowns. He is rescued but not before his abandonment at sea drives him mad. For the rest of the novel, Pip wanders the ship speaking a kind of prophetic, ‘crazy-witty’ gibberish; he is a replay of William Shakespeare’s mad fool. Pip’s ‘brilliancy’ – his humanity – is transformed into an equally human madness that attracts Lear-like Ahab. In the novel’s dramatic conclusion, Ahab and Ishmael, too, are bumped from their shared whaleboat, just as mad Pip had been bumped. Their separate bumpings enact Ishmael’s singular prediction at the end of Chapter 93 that the cabin boy’s leap is a ‘like abandonment that befell myself’. These similar fates seal a black-white bond tying Pip, Ishmael, and Ahab together (Bryant, 2021, pp. 777–82).

The transformation of Pip from a comic Black cohort in a racialised diptych to the unifying Black thread that ties him to Ahab and Ishmael in a tragic triptych is easily read as character development only. But external, biographical evidence along with the curious, unresolved inconsistency of Pip’s place of birth – the apparent remnant of an incomplete revision – suggests that Melville’s plans for Pip changed radically as he wrote Moby-Dick.

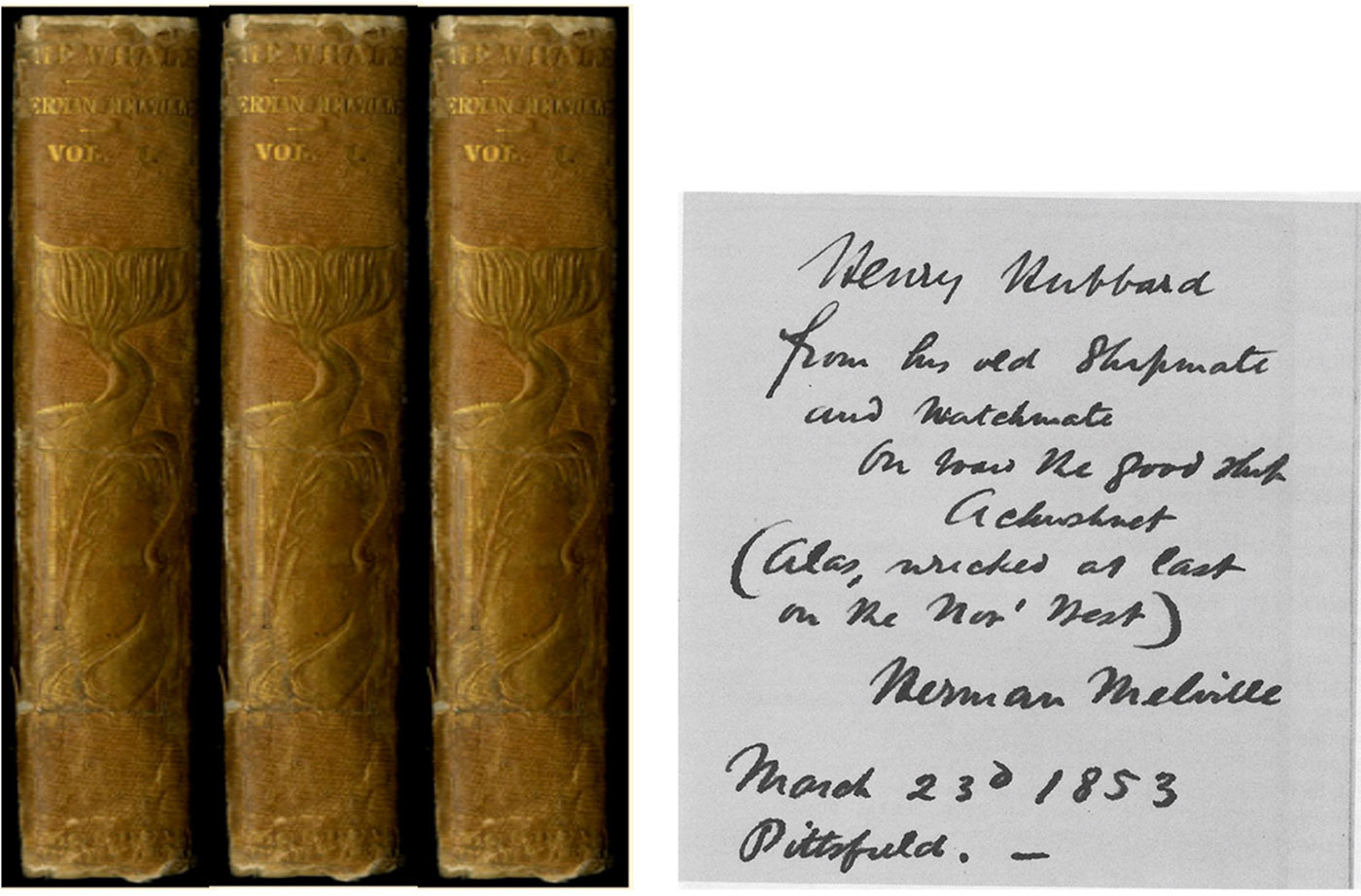

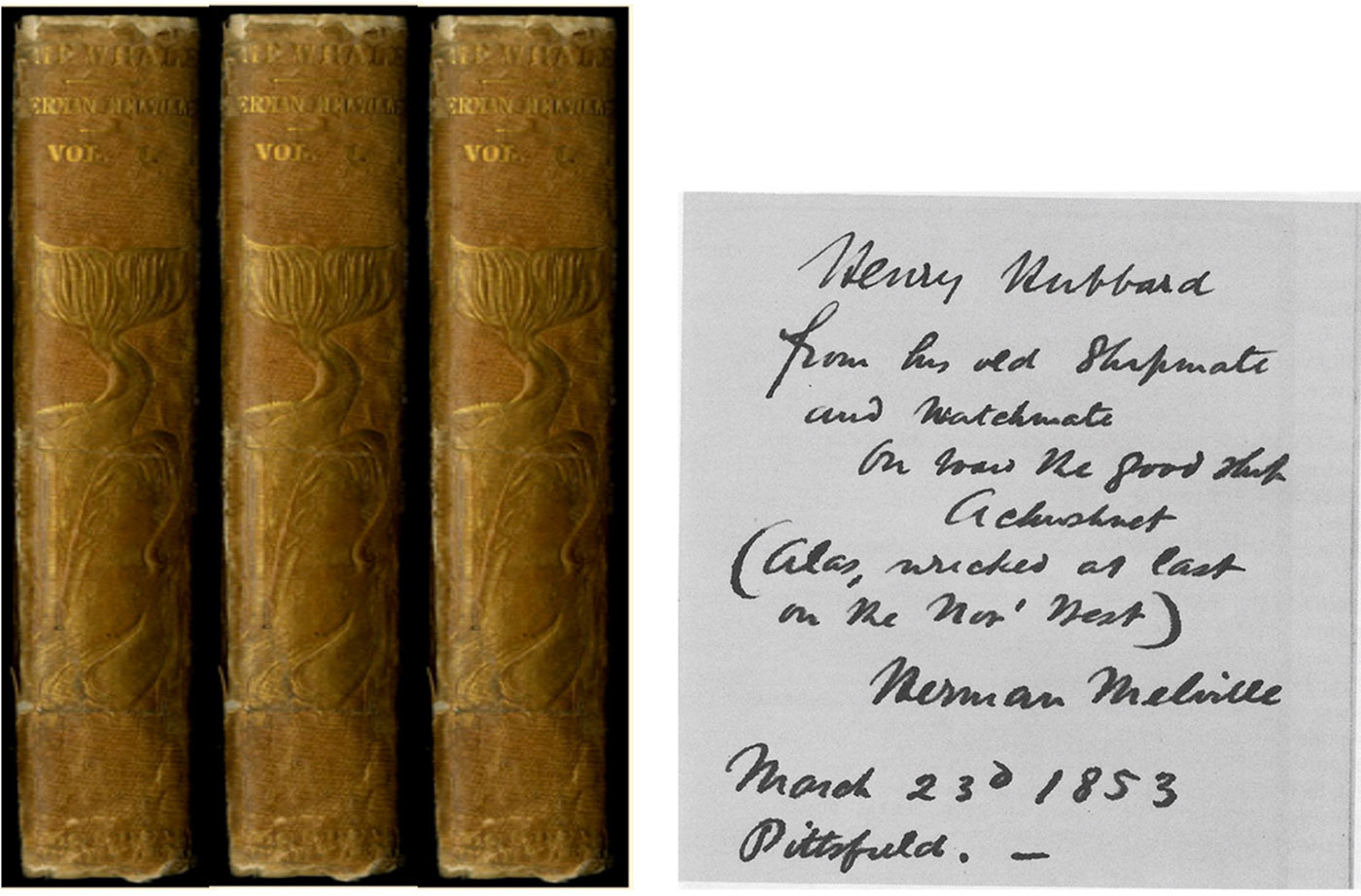

Clues concerning the biographical source for Pip are found in evidence of a visitor that Melville received at his Pittsfield home, in 1853, two years after the publication of Moby-Dick. The visitor was Henry Hubbard, a former shipmate on Melville’s first whaling ship Acushnet. The two had signed on board at the same time, out of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, were watchmates standing guard at nights, and became fast friends during their eighteen months at sea together. While Melville jumped ship at Nuku Hiva in 1842, Hubbard stuck to the Acushnet until it returned home. A decade later, in 1853, Hubbard found himself visiting relatives in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where his old acquaintance Herman Melville (now a famous writer) was also residing. The two salts reminisced for hours at Melville’s ‘Arrowhead’ homestead, and as a memorial of their visit, Melville presented ‘his old shipmate and watchmate’ with a signed copy of the three-volume 1851 British edition of Moby-Dick, titled The Whale (see Figure 1).

Source: PS 2384.M7 1851a, copy 2, Helen and Ruth Regenstein Collection of Rare Books, The Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago

It reads: ‘Henry Hubbard / From his old Shipmate / and watchmate / On board the good ship / Ackushnet / (Alas, wrecked at last / on the Nor’ West) / Herman Melville / March 23d 1853 / Pittsfield. –’

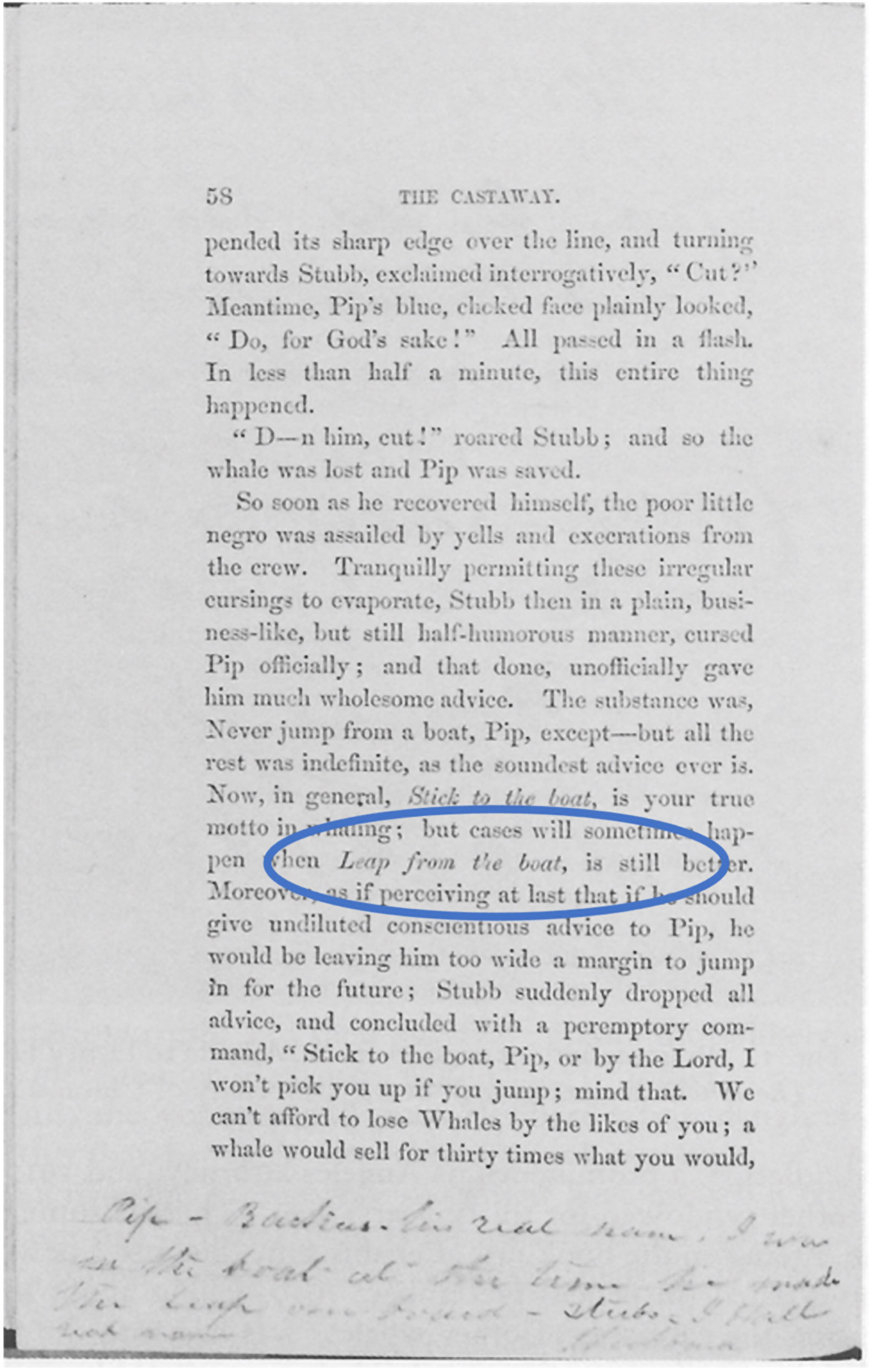

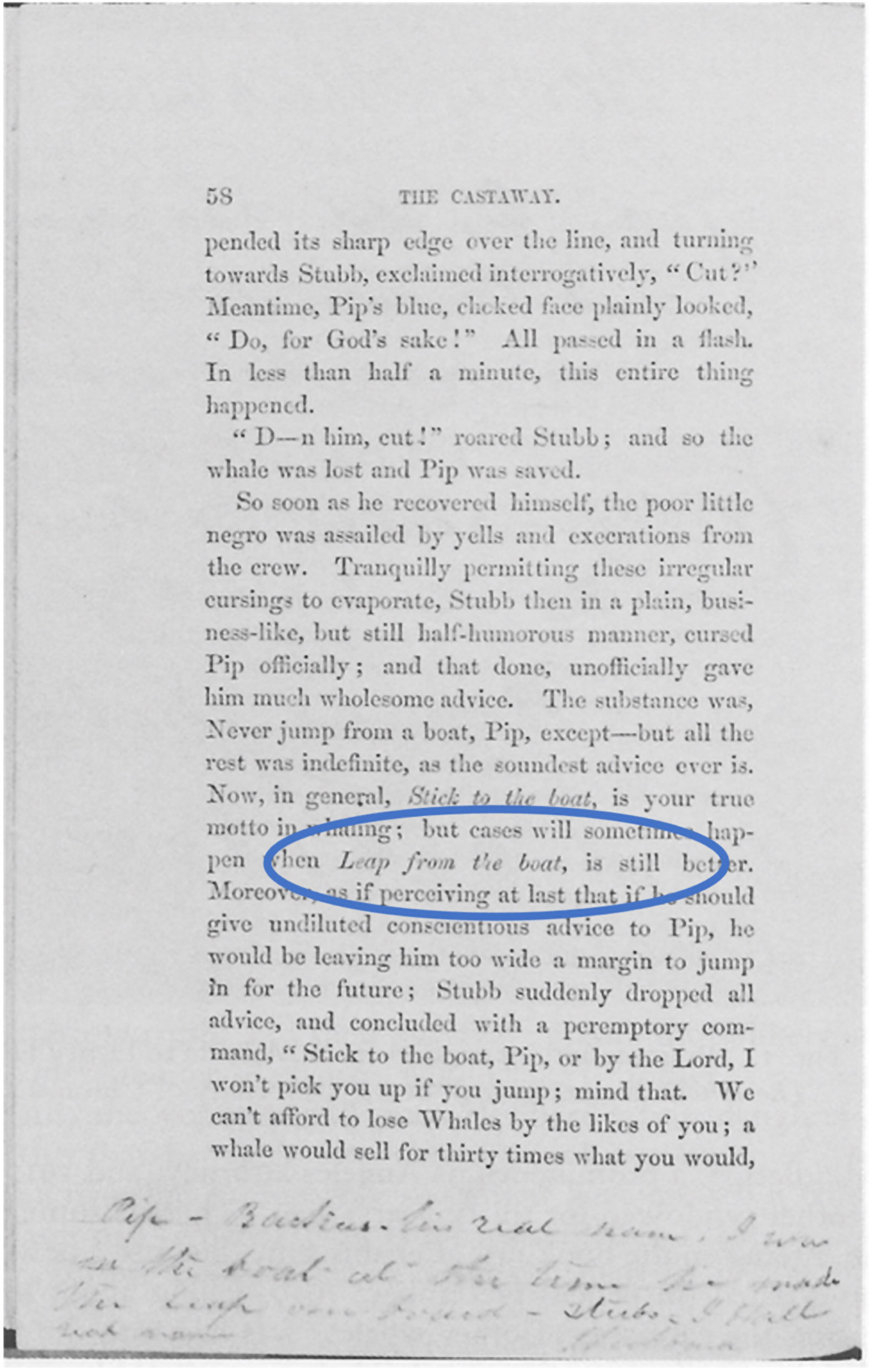

Chances are Hubbard had not read his shipmate’s novel, and never would, but a single annotation in the copy Melville gave him – presently archived at the University of Chicago’s Special Collections – confirms not only Hubbard’s interest in the book but also the fact Pip was based on a real person. At the bottom of the page that relates Pip’s leap, Hubbard inscribed the following: ‘Pip – Backus his real name. I was in the boat at the time he made the leap overboard’ (see Figure 2). Hubbard’s signed note is the volume’s only marginalia; it is not one of numerous other markings that we might find as a record of a reader’s close engagement with a book. Apparently, shipmate Hubbard was not much of a reader. Why, then, this single and singular note, buried in Volume 3? Rather than a close reading, it represents a moment of shared reminiscence in his 1853 meeting with Melville.

Source: PS 2384.M7 1851a, copy 2, Helen and Ruth Regenstein Collection of Rare Books, The Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago

It reads in full: ‘Pip – Backus his real name. I was / on the boat at the time he made / his leap over board – / Stubs, J. Hall / his name. / Hubbard’

Evidently, the former shipmates spoke of old times at sea and whatever happened to the rest of their crew. Naturally, Backus and his memorable leap came up in conversation. Inevitably, Melville opened his novel to ‘The Castaway’ where Hubbard and Backus figure in Pip’s leap. Presumably proud that he was ‘on the boat’ when Backus leapt and proud to be part of Melville’s book, Hubbard proudly corroborated their shared biographical moment in the only annotation he would make in his copy of the book.

Other external documents add more detail. After Hubbard and Melville parted, Melville composed a list of shipmates that he titled ‘What became of the ship’s company of the whale-ship “Acushnet”’. Included in the list is a crucial identifier: ‘Backus – little black’. Apart from indicating Backus’s race, the entry ‘little black’, suggests that Backus was not a youngster, or cabin boy, but a diminutive adult sailor. Ship’s records further identify him as ‘John Backus’.6

How does this archival biographical fact of John Backus affect our reading of Moby-Dick? To begin with, Backus’s leap tells us that Melville did not invent Pip simply to fill an aesthetic need for a sympathetic mirroring of Ishmael, Ahab, and crew. He transformed Backus into Pip to address personal needs. Moreover, the transformation involved discernible stages of revision that magnify the psychological and cultural relevance of Pip’s trauma.

The first revision step was to convert the ‘little black’ adult named John Backus into the fictional Black cabin boy named Pip. This conversion is fraught with cultural anxieties. In ‘The Castaway’, Melville deploys racial stereotypes in describing Pip’s ‘jolly brightness peculiar to his tribe; a tribe, which ever enjoy all holidays and festivities with finer, freer relish than any other race’. As benign as this tribalism may seem, it would be pernicious except in the context of white Ishmael’s subsequent counter-argument that Black Pip is ‘brilliant’ because of his blackness. In short, the tribalism deconstructs as Ishmael turns the tables on his readers: ‘Nor smile so, while I tell you this little black was brilliant’ (Chapter 93).7 Ishmael assumes a racist readership that will instinctively ‘smile’ at Ishmael’s outrageous presumption of Pip’s brilliancy. His rhetorical strategy is to replay cultural stereotypes only to replace them with the humanising drama of Pip’s leap, and Pip is made less racialised and all the more sympathetic through the poignancy of his prophetic madness.

The second step in Melville’s transformation of Pip is the revision of the adult male Backus into the boy Pip. Here, too, Melville’s apparent infantilisation of a Black man verges on racial derogation. Of course, Pip’s status as a child working in an adult environment automatically enhances his vulnerability and thereby our empathy: this ‘castaway’ on a heartless sea is just a kid, a pippin, a pip. But Melville also crafted Pip to resemble his own boyhood. In 1832, when Melville was twelve and about Pip’s age, his father died from exposure while travelling several days in sub-zero weather; his fever went to his head and resulted in a period of deranged ravings and recitations from the Bible. Though Hubbard’s annotation does not disclose the psychological effects of Backus’s leap, Melville makes a point of showing how the ‘gloomy-jolly’ Pip becomes ‘crazy-witty’, not unlike Melville’s father in his final weeks of biblical ramblings. In effect, Melville was reshaping adult Backus into young adolescent Pip to resonate with his own orphan status and sense of ‘abandonment’. Like Pip, and like Ishmael, Melville felt he was a ‘castaway’. In bringing the ‘little black’ Backus closer in age to himself at the time of the loss of his father, Melville also associates himself with the condition of being Black. By inhabiting Pip, Ishmael does not play the role of a Black person – he is not, strictly speaking, ‘blacking up’ – but adopts a black consciousness of social and mental dispossession.

A curious textual inconsistency in Moby-Dick brings Black Pip even closer to white Herman. Melville introduces Pip first in ‘Knights and Squires’ (Chapter 27), identifying ‘Black Little Pip’ as a ‘poor Alabama boy’, and therefore a slave. However, in ‘The Castaway’ and ‘The Doubloon’ (Chapters 93 and 99), Pip is a ‘native’ of ‘Tolland County, Connecticut’, and therefore free. Scholars have yet to track down why Melville specifies Tolland County. Perhaps, on board the Acushnet, Backus had disclosed it as his home, and Melville would have taken note because Tolland County is not distant from Melville’s homes in Albany and Pittsfield. Regardless, the internal inconsistency of Pip’s birthplace suggests that Melville revised his initial conception of Pip not only from comic to tragic but also through versions of Blackness. Pip’s initial Alabama Blackness associates him with abject southern slavery. His subsequent Connecticut Blackness identifies his northern freedom and proximity to Melville’s predominately white readers. In transforming Backus into Pip, Melville was able to work through his adolescent father-loss and adult Ahab-anger while nurturing a black consciousness that had been growing in him since childhood.

We do not have to read Pip biographically in order to appreciate the aesthetic impact of his character in Melville’s tragedy. But once we reckon Backus as a biographical presence in Melville’s transformation of Pip, and once we find substance in this figure’s evolution, we rise to a fuller aesthetics that encompasses the ragged edges and incompleteness of Melville’s revision practice: his essaying of his past, the erupting of the memory of a shipmate’s leap into his narrative, the always growing and changing course of Blackness in his own consciousness and in his culture. He was showing himself and his readers how a Black life matters.

This aesthetics of incompletion continued to evolve throughout Melville’s creative life and is most evident in another sudden eruption of memory: the late insertion of an African sailor during the composition of Billy Budd.

Billy Budd is Melville’s last prose work. Left in manuscript at his death in 1891 and published posthumously in 1924, it is ‘finished’ in its narrative arc, but since Melville never prepared the heavily revised manuscript for publication, his text remains radically incomplete.

As a narrative, Billy Budd is one of the most wrenching tragedies in modern literature. In the aftermath of the Great Mutiny of 1797 during the Napoleonic wars, and on board the British warship Indomitable, Billy is a ‘Handsome Sailor’, both powerful and beautiful yet a beloved peacemaker among the crew; however, he stutters when angry and is capable of lightning violence. When the master-at-arms John Claggart falsely accuses him of mutiny in the presence of the Indomitable’s Captain Vere, Billy cannot control his emotion and strikes Claggart dead. Knowing the extenuating circumstances but presuming the crew will take any act of mercy on his part as weakness, Vere arranges a drumhead trial, insists on a guilty verdict, and condemns Billy to hang. Billy accepts the sentence and at execution calls out, ‘God bless Captain Vere,’ which the crew in unison repeats. Shocked by this unexpected affirmation, Vere stands ‘rigid as a musket’. Soon after, having been wounded in battle, he dies, uttering ‘Billy Budd, Billy Budd’. The novella ends with a sailor ballad, performed in Billy’s voice, as he awaits execution.

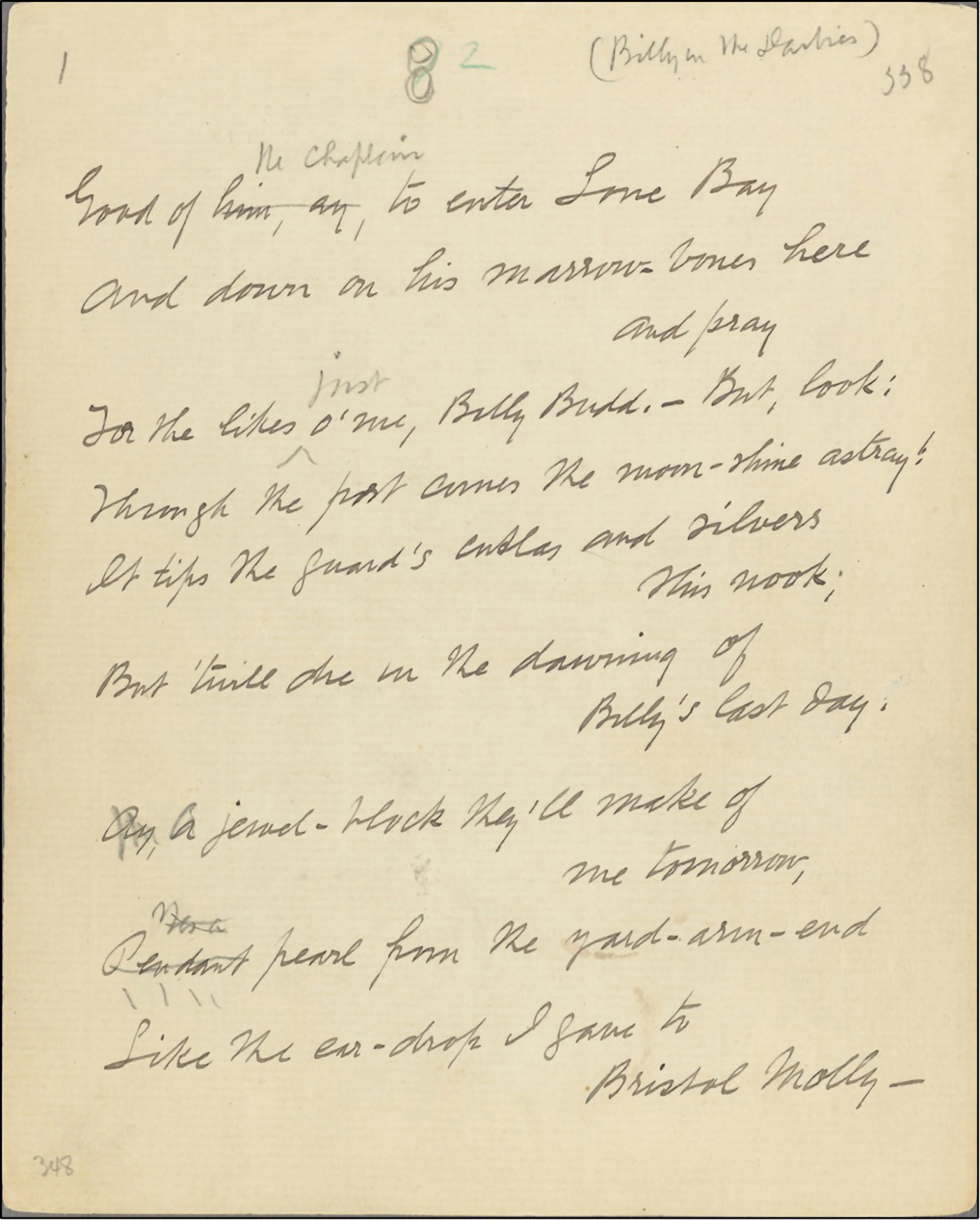

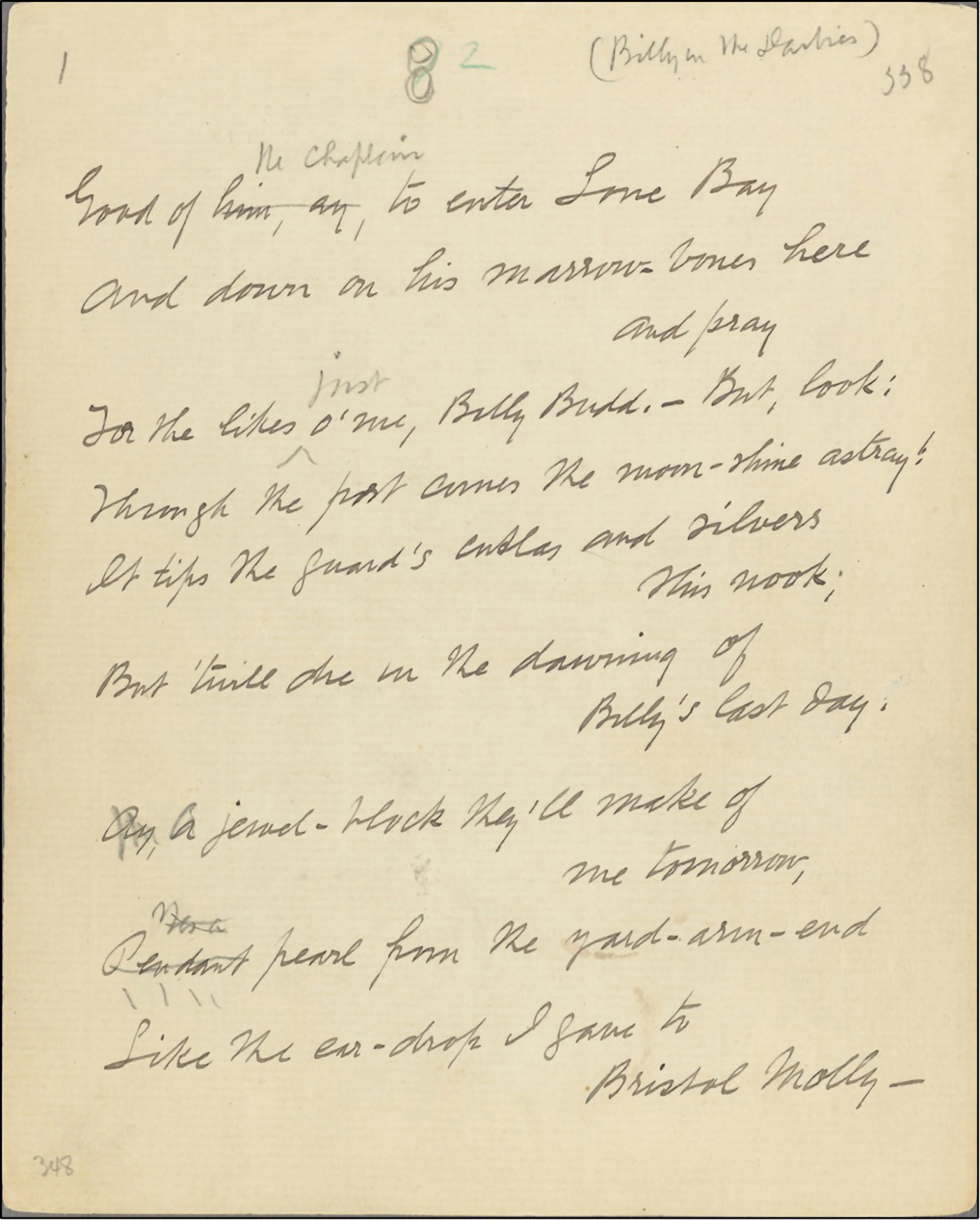

While Melville’s tragedy is a tightly structured narrative, its heavily revised manuscript reveals a more complicated revision narrative, making the novella one of Melville’s most intriguing fluid texts. Melville first conceived of Billy Budd as a stand-alone version of the poem that now concludes the novella. In it, Billy is an experienced sailor, part of the bellicose gun crew below decks and called ‘Beauty’, who is guilty of mutiny and awaiting execution. Affixed to the poem was a brief, scene-setting headnote in prose. But as the headnote grew, chapter by chapter, into a novella, the poem’s guilty gunner Billy was transformed into the innocent foretopman we now know.8

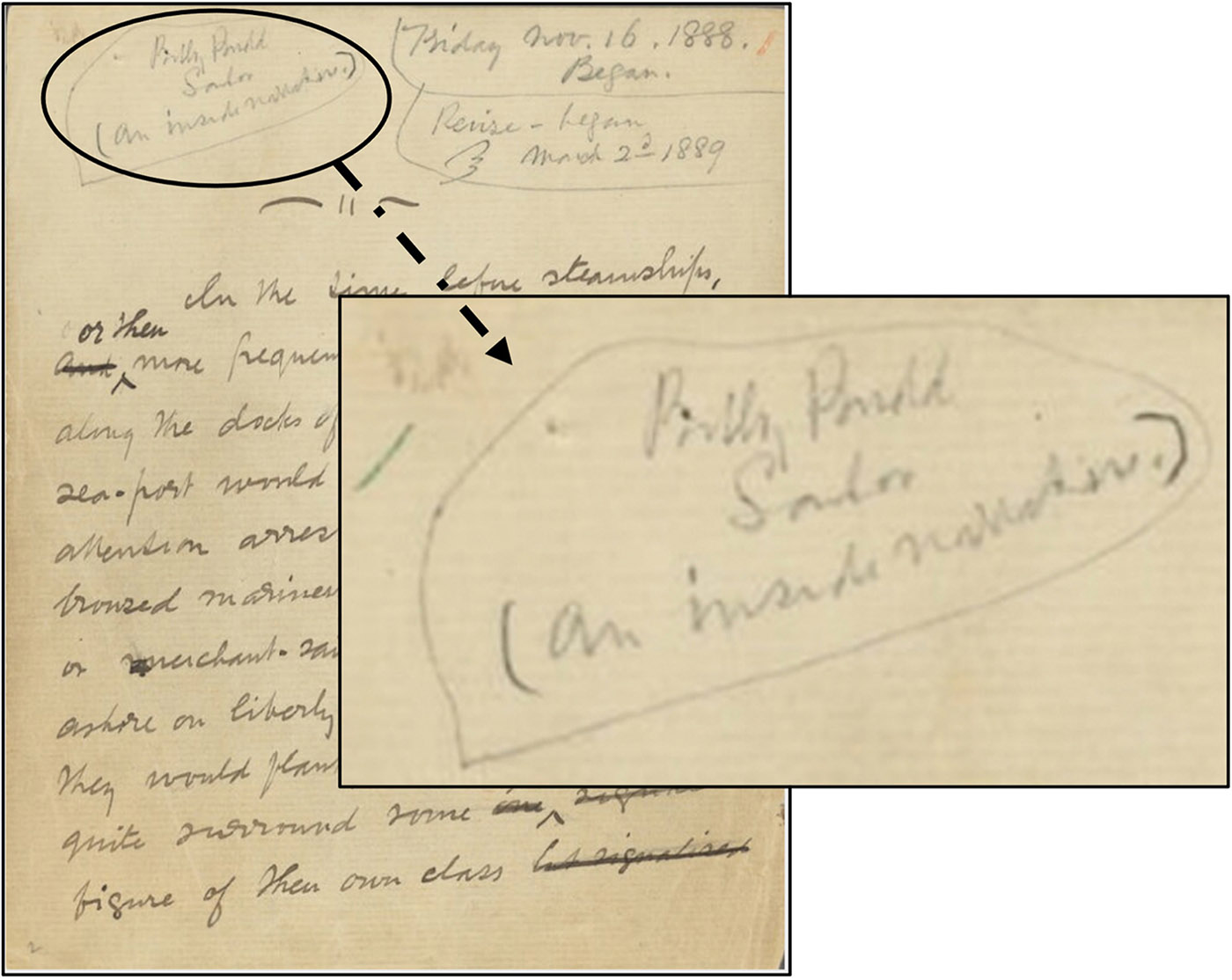

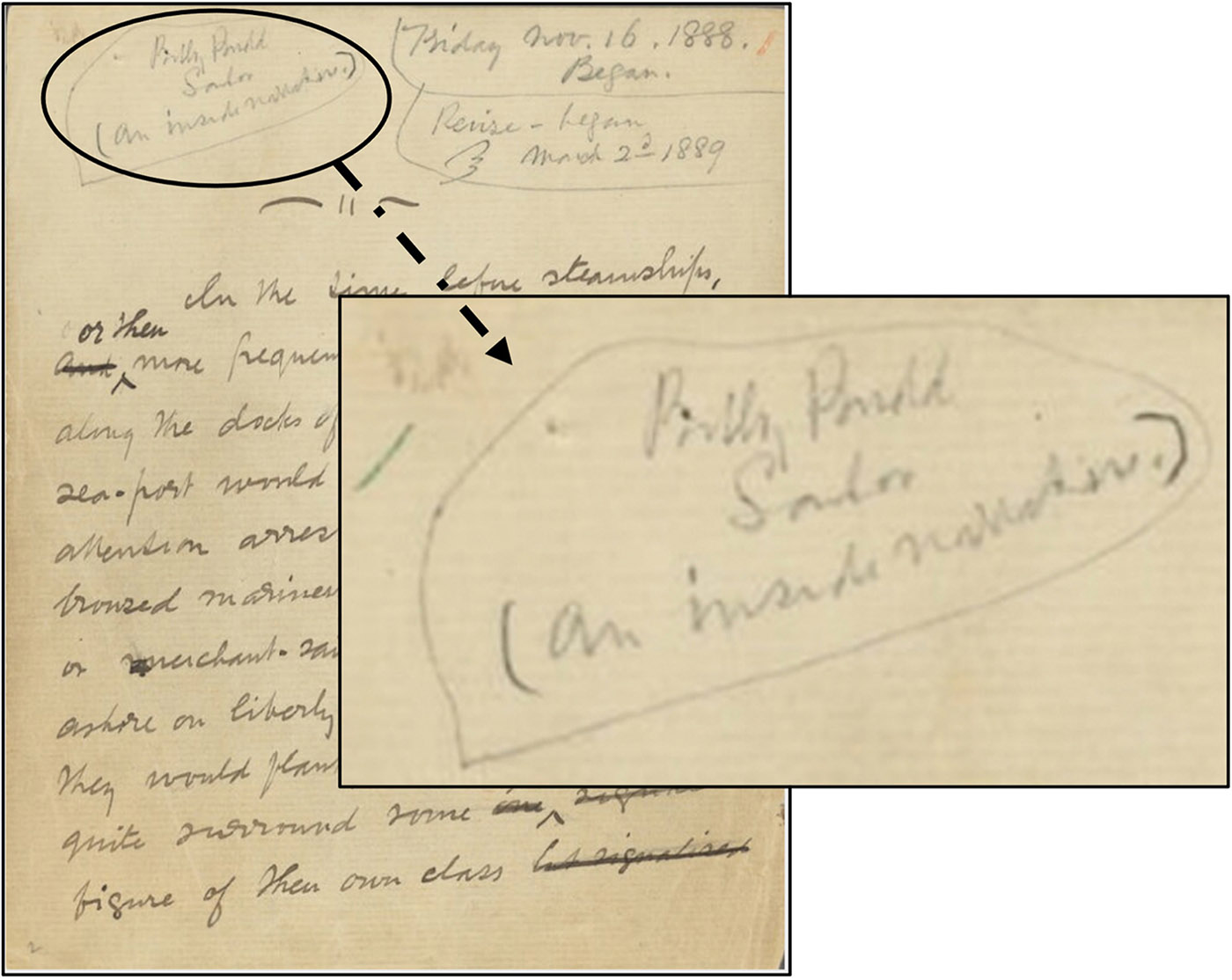

The two-leaf headnote in prose grew through three overlapping versions into a 360-leaf manuscript. First, Melville added Chapters 1–5, introducing Billy as an exemplar of the ‘Handsome Sailor’ type. He then split and expanded existing chapters and added others to create Chapters 6–12, which recount the inexplicably malevolent Claggart’s attempts to trap Billy into mutinous behaviour. Later, he added Chapters 13–27 involving Vere, the trial, and Billy’s execution. Even later, Melville composed three concluding chapters (28–30) that relate Vere’s death, a false newspaper account of the affair, and a new introduction to the newly revised poem. At or near the end of his revisions, Melville retitled his work as ‘Billy Budd / Sailor / (An inside narrative.)’ and gave its concluding poem its own parenthesized title, ‘(Billy in the Darbies)’.

At other stages throughout his expansions, Melville revisited all that he had composed, in many cases modulating his narrative voice. One striking instance of narratorial intervention, involving heroes, magnates, and race, is evident in the manuscript’s opening leaves.

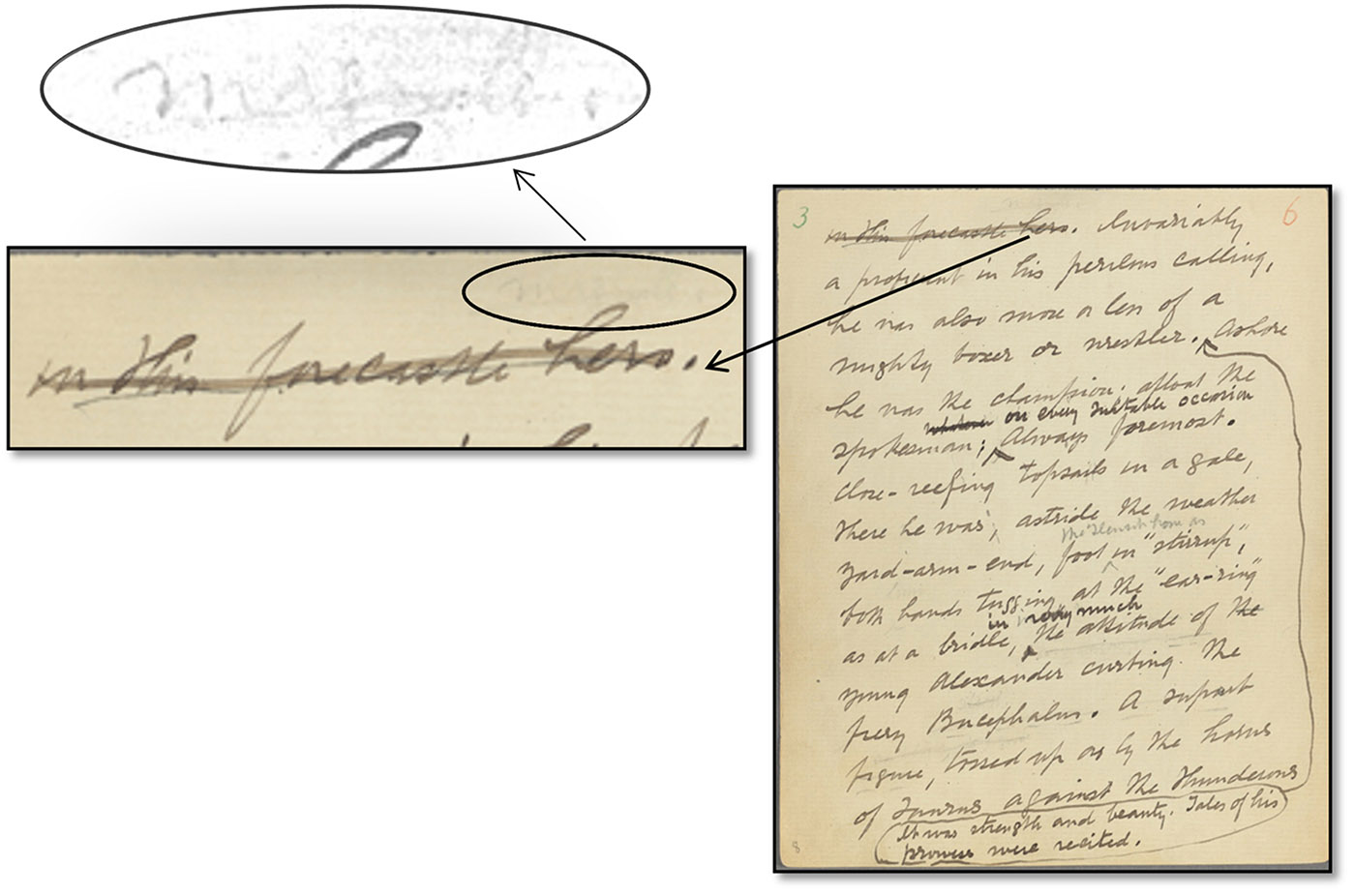

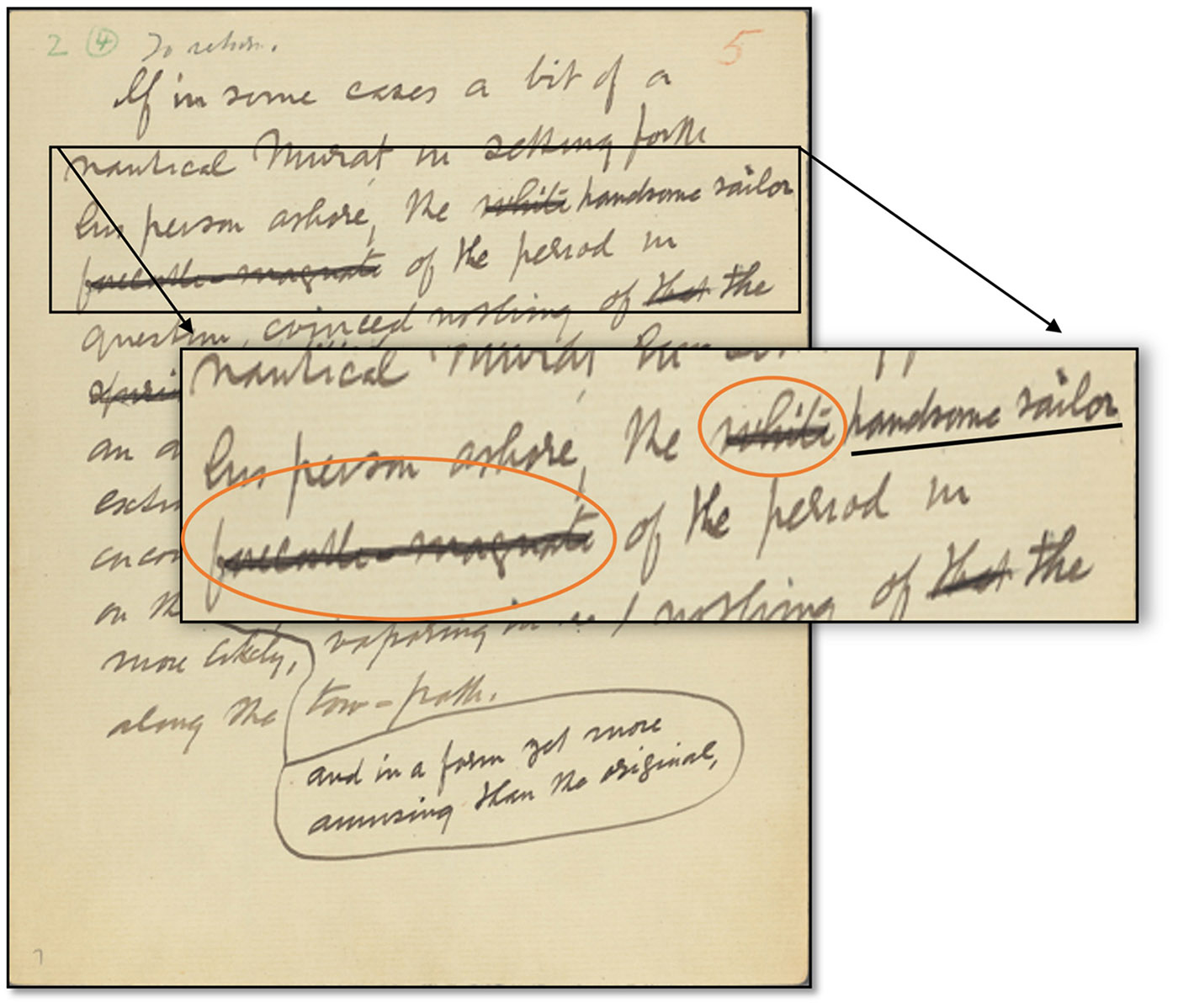

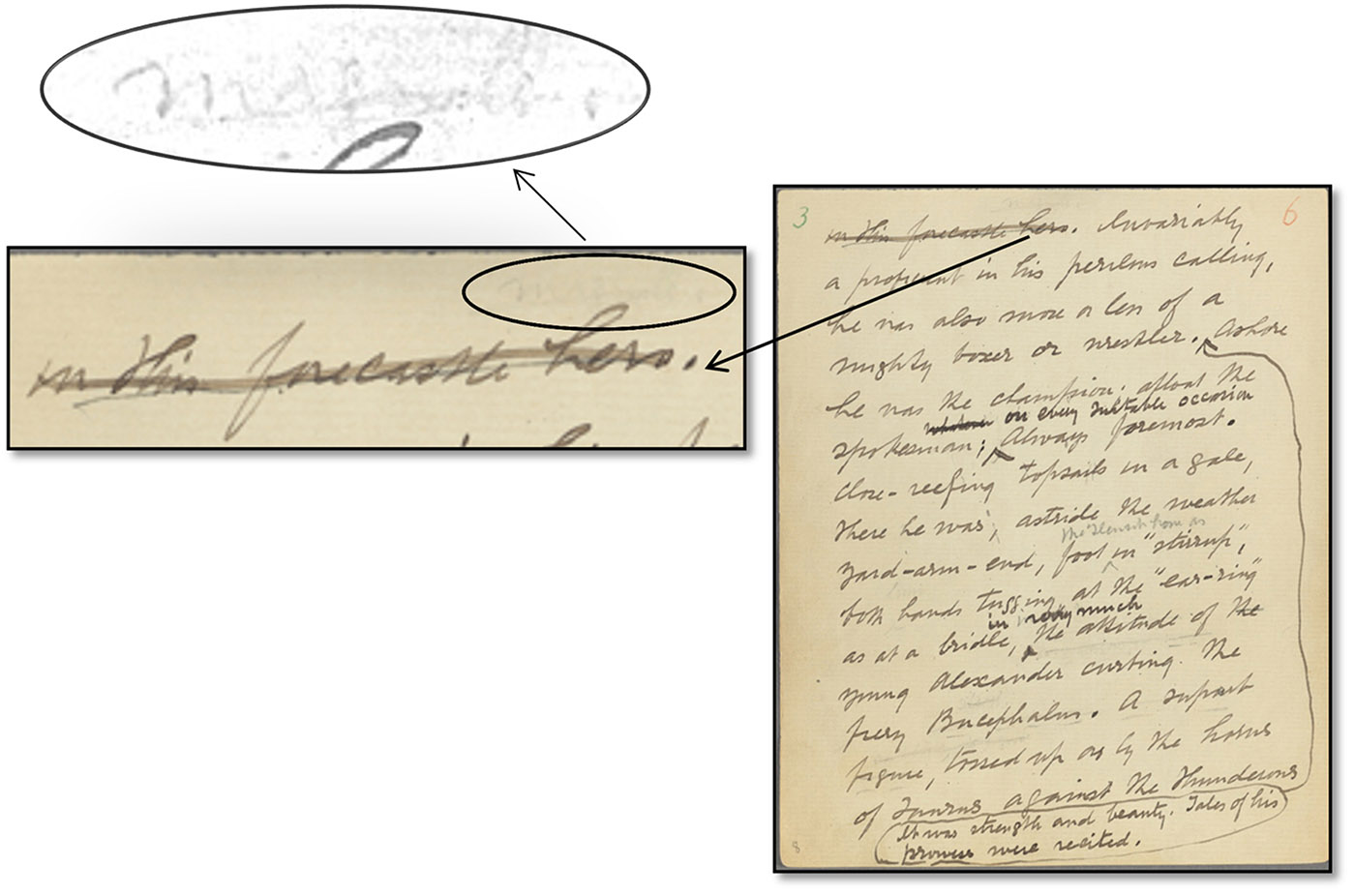

Initially, Billy Budd had opened by introducing the ‘Handsome Sailor’ as an inspiring maritime type universally loved for his ‘strength and beauty’ and ‘masculine conjunction’ of ‘comeliness and power’. In this version, Billy is the only exemplar of this ‘forecastle hero’ type, that is, a champion among the common sailors, who congregate at the bow of the ship, or forecastle. But at some later point, over the word ‘hero’, Melville tentatively inscribed in pencil an optional revision, the word ‘magnate’. Apparently, this word struck Melville’s fancy. He imperfectly erased ‘magnate’ then deleted ‘forecastle hero’ altogether, and added ‘white forecastle-magnate’ to a set of leaves preceding the deleted ‘forecastle hero’ (see Figures 3 and 4).

Source: Herman Melville Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS AM 188 [363]

Melville’s deletion of ‘forecastle hero’ appears on the first line of leaf 8. Barely visible even in the magnified inset, and directly above ‘hero’, Melville pencilled the word ‘magnate’ as a suggested revision, then erased it when he deleted ‘forecastle hero’. Later, in inserting leaf 7 to precede leaf 8, Melville combined the deleted words to give ‘white forecastle-magnate’ (see Figure 4).

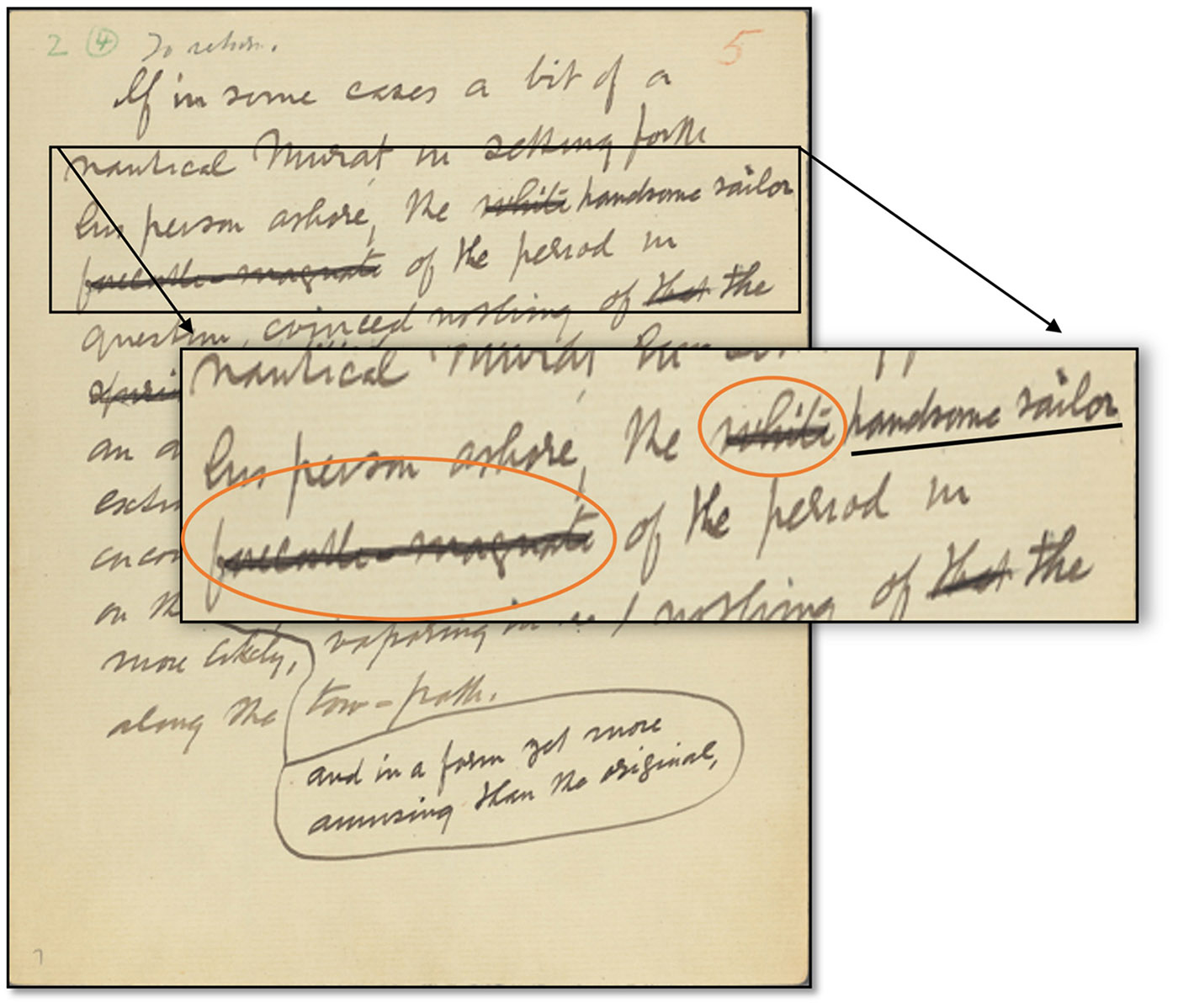

Source: Herman Melville Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS AM 188 [363]

Melville’s careful fair-copying of ‘white / forecastle-magnate’ in ink indicates his certainty, at the time of inscription, of the phrase. But he deleted it, first in pencil, and then in two ink strokes. At the same time, he added ‘handsome’ and ‘sailor’, either together or separately, in the space and margin to the right of ‘white’. The arrangement of deletions and insertions suggest at least two revision sequences as to whether Melville removed ‘white’ first or last in his process.

At the same time or thereabouts, and, apparently, as he was reviewing his modified description of the charismatic ‘Handsome Sailor’ type, Melville recalled – or so he has his narrator say in another new set of leaves he would soon insert – an episode from the narrator’s past. In revision, Melville’s narrator claims that ‘half a century’ earlier, in Liverpool, he had witnessed an ‘intensely black’ and charismatic African, who ‘sallies’ about Prince’s Dock and gathers about him a throng of admiring shipmates, who take ‘pride in their mighty black sailor’. With this new figure, the added ‘black pagod of a fellow’ conflicts with, indeed seems to be a replacement of the already present ‘white forecastle-magnate’ as an exemplar of the ‘Handsome Sailor’ type. Two sets of revision were at odds.

A significant biographical fact in the dynamics of the African sailor revision is that its eruption out of the fictional narrator’s memory is true to Melville’s life. In 1839, nineteen-year-old Melville had sailed as a greenhorn out of New York on board the St Lawrence to Liverpool, where he spent six summer weeks on Prince’s Dock. Now, in 1889, precisely ‘half a century’ later, Melville’s micro-revisions of Billy Budd had triggered a memory from adolescence that in turn triggered a macro-revision of his evolving ‘Handsome Sailor’ type. Liverpool had been the third point in the slave-trade triangle, importing products such as cotton from slave nations and exporting fabrics to Africa to be exchanged for slaves. It was also a cosmopolitan port with vibrant Black and mixed communities. Moreover, three of Melville’s shipmates aboard the St Lawrence were African Americans.9 In his 1849 Redburn, Melville recounted his observations of these and other Black figures during his Sailor-town experiences along Liverpool’s docks, and these events and narratives figure strongly in the evolution of white Melville’s black consciousness. But Redburn makes no mention of the flamboyant African sailor that he would add to the opening of Billy Budd. Nevertheless, a chain of memories involving beauty and blackness, race and class, life and text, wakened in Melville as he revised.

The African sailor insertion inevitably led to further revisions. Simply put, the insertion of the joyous, handsome African sailor as ‘intensely black’ now rivalled the earlier revised epithets for the sailor type as first a ‘forecastle hero’ and then a ‘white forecastle-magnate’. One problem is that the word ‘magnate’ is particularly inapt for his heroic handsome sailor. Given that the lot of forecastle sailors he had worked with and admired were largely dispossessed underclass comrades, the upper-class connotations of political and entrepreneurial power made ‘magnate’ an unlikely forecastle term. Another problem was ‘white’.

From his earlier years in Manhattan, Albany, and at sea, Melville had developed an empathy for the dispossessed that excluded no ethnicity, and the use of ‘white’ as a descriptor for racial supremacy is rarely found in Melville’s writing. When that word emerges, notably in Typee or White-Jacket or Moby-Dick, it carries psychological and metaphysical implications that invariably preclude or even, as with Pip, dismantle racist assumptions. Perhaps, then, with some sense of the double inadequacy of ‘white forecastle-magnate’ and triggered by memories that reignited his formerly engaged but nodding black consciousness, Melville returned to the previously inserted ‘white forecastle-magnate’, deleted ‘white’, then deleted ‘forecastle-magnate’, and added instead ‘handsome sailor’. Although in the final reading text of Billy Budd, ‘welkin-eyed’ Billy is decidedly white, the ‘Handsome Sailor’ type that he embodies comes to readers first as a memorable African version of male beauty, which in tandem with Billy, is taken as neither essentially white nor Black, upper-class nor working.10

Biographers and critics may fairly ask why Melville racialised his ‘Handsome Sailor’ type as white to begin with. It would be easy to rely on the bromide that the ageing writer simply ‘nodded’ (as if literary ‘genius’ somehow excuses such humanising lapses in our hagiography); or argue, in his defence, that people were more ‘casually racist’ in Melville’s day (as if we are not differently though equally so today). But such approaches ignore the concrete evidence of how Melville’s or any writer’s creative process may transpire, intentionally, experimentally, accidentally, and even despite oneself. Rather, we look to how textual evolutions reveal rhetorical strategies designed, it would appear, to manipulate readers into more complicated relations with colour, class, and race.

Just as he deployed images of brilliance in Moby-Dick to familiarise Pip’s blackness, Melville promotes a kind of readerly involvement with blackness in Billy Budd by ‘defamiliarising’ whiteness. Around the same time that Melville was inserting his African sailor in Chapter 1 and revising ‘white forecastle-magnate’ in and out of existence, he was also modulating his descriptions of Billy’s complexion. Melville’s narrator makes clear that Billy is English and purely Saxon, without any ‘Norman or other admixture’ (Chapter 2). But resisting presumptions of Billy’s racial purity, Melville also compares Saxon Billy’s face to the repose found in Greek statues of Hercules, which is, in turn, ‘subtly modified’ by Billy’s ‘orange-tawny’ hands stained by the tar bucket. Furthermore, ‘tawny’ (meaning tanned) describes any dark complexion, and Melville used the word to describe himself upon his return from Liverpool.11 This aestheticized ‘admixture’ of marble-white repose and working-class colour further suggests Billy’s illegitimacy: he is a by-blow of mixed-class lineage. In further instances, his whiteness is transformed into the ‘rose-tan’ of his ‘ruddy’ complexion (Chapters 12 and 24). Strictly speaking, Billy is not ‘white’ in colour or class.

As Melville ‘subtly modified’ Billy’s racial whiteness into the warmth of his rose-tan, he was also lending an alien aspect to his rare uses of ‘white’ and its pallid associations. For instance, when Billy learns of his death sentence in Chapter 19, his ‘rose-tan’ pales as if ‘struck as by white leprosy’. And given Billy’s brief incarceration in the ship’s dark hold before his execution, Melville observes in Chapter 24 that not enough time had elapsed for the ‘effacement’ of ‘pallor’ to offset Billy’s tan. Just as Melville had complicated ‘the whiteness of the whale’ and the blackness of Pip in Moby-Dick, his use of ‘white’ as a racial descriptor in ‘white forecastle-magnate’ is all the more inadequate for the tanned, mixed class, remarkably handsome sailor Billy.

Systemic racism is a habit so ingrained in postcolonial culture that it may seem an instinctive structure of mind. It shapes our sense of the past, colours our fears, infects our vision, seeps into our discourse, and yet it may erupt despite ourselves. But habit is not fate, and racism can be unlearned. We may forgive and forget Melville’s ‘white forecastle-magnate’, but the narrative of its coming and going is more meaningful if we pursue the narrative of its ‘ragged edges’ as we read Billy Budd and our culture. Melville’s use of ‘white’ in his essaying of the ‘Handsome Sailor’ type is a dynamic of its own: not so much a nodding off as a momentary forgetting of himself followed by revisions that unspeak the word, retrieve an identity, and deepen his black consciousness. As Toni Morrison puts it, Melville was able to ‘unhobble the imagination’ from our ‘racially inflected language’ (1992, pp. 13, 38).

As previously noted, revision is an invisible phenomenon. While we can see a deletion and insertion graphically displayed in manuscript, we cannot ‘see’ the creative steps between those inscribed endpoints of the revision. If we want to take the study of a fluid text beyond guessing – and if we want to extend the discussion of revision to broader interpretive communities – then we must curate and visualise the invisible steps of revision. We must edit them into visibility.

One problem with conventional editions of Billy Budd is that they offer smooth reading texts representing the editors’ conception of Melville’s final intentions and invariably consign revision texts – the ragged textual evidence of his decisions and indecisions – to the hard-to-read, abstract lists of a textual apparatus. Moreover, because leaf reproductions in print are expensive and cannot be magnified, print editions provide little or no on-the-page access to Melville’s manuscript. As a consequence, readers have no direct access to revision and the idiosyncratic etymologies of Melville’s words they reveal, nor to how Melville essayed himself into and out of the revisionary dilemmas discussed above, nor to how Billy Budd is a radically incomplete work. In Chapter 1, the reader will come to ‘handsome sailor’ in the edition’s reading text and simply read on, not knowing that the phrase had once been ‘forecastle hero’ and ‘white forecastle-magnate’, or even knowing to ask about how the phrase evolved.

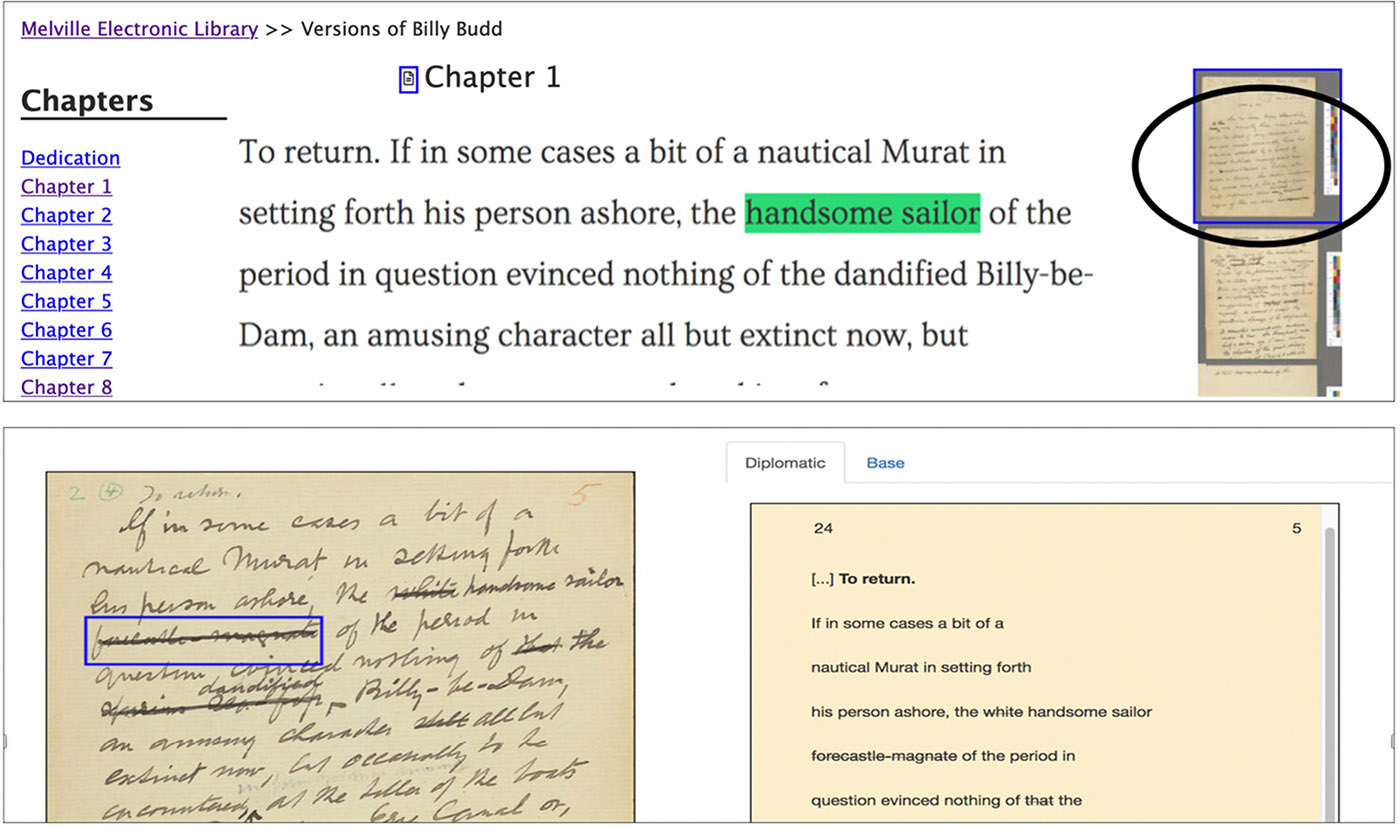

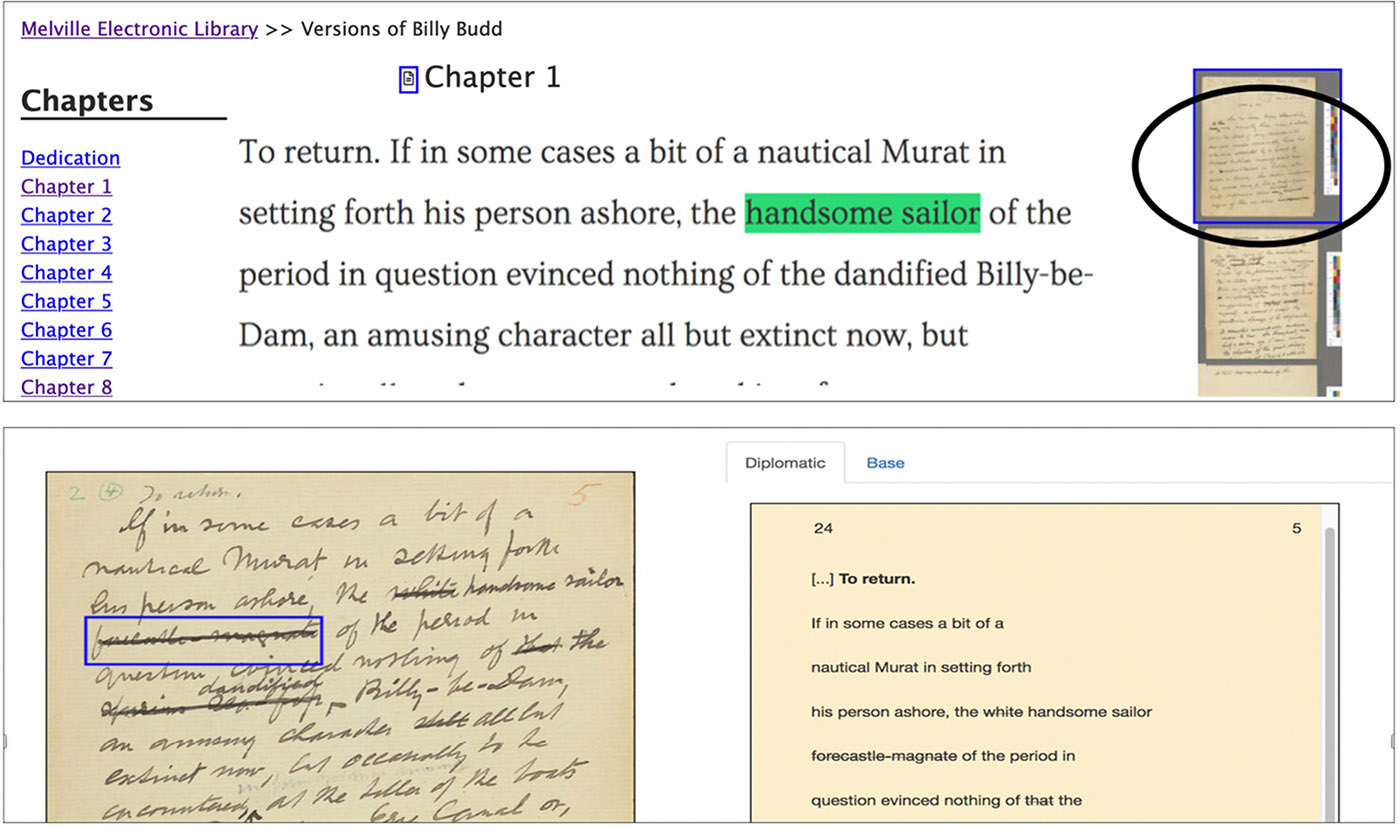

The Melville Electronic Library (MEL) takes a different approach in its fluid-text edition of Billy Budd. Like any edition, it also offers a reading text smooth enough to afford readers the pleasures of Melville’s narrative. It differs, however, in that it is also rough enough to signal incompletions.12 It provides in-text icons and marginal thumbnails enabling readers to access the edition’s leaf images, diplomatic transcriptions, and the ragged edges of Melville’s development of Billy, Claggart, and Vere. In emulation of its Moby-Dick edition, MEL supplies revision narratives tracing the growth of Melville’s never-quite-complete, three-person tragedy (see Figure 5).

Source: https://melville.electroniclibrary.org/editions [accessed 25 March 2025]

In MEL’s editorial design for Billy Budd, reader’s click on marginal thumbnails to access side-by-side leaf images and their diplomatic transcriptions for highlighted revision sites in the reading text. The transcription emulates the positioning of Melville’s revision texts and enables readers to decipher his handwriting and obscured or incomplete inscriptions.

Equally significant is the unreliable narrator who seems never fully to tell his ‘inside narrative’. Editing enables us to ‘see’ the growth of that indeterminate voice. In essaying the dimensions of his voice, Melville was simultaneously enacting his aesthetics of incompletion.

Let’s return to Melville’s abrupt insertion of the African sailor but from a different perspective. Here, biographical writer and narrative voice suddenly diverge as Melville’s personal memory unexpectedly intrudes upon what we assume has been an objective third-person narration. Melville’s seemingly omniscient, confidently historical, suitably detached voice suddenly transforms into an intrusive speaker who calls himself ‘me’. This I-voice cannot prevent himself from sharing a memory that ‘recurs’ to him; he drags us into his personal past. Never a character in the action, this erratic first person nevertheless intrudes again, throughout the narrative, unpredictably, from time to time, as a vexed observer of the ‘ragged edges’ of his own narration, trying to make sense of not just Billy, Claggart, and Vere, but himself. His eruptive reminders of the impossibility of knowing the truth also undermine his credibility as a conventional storyteller. One scenario in the evolution of this vexed first person involves his revision of his title for Billy Budd.

Melville’s initial title, ‘Billy Budd, Foretopman: What befell him in the year of the Great Mutiny, &c.’ promises a historical narrative, and Melville’s opening line ‘In the time before steamships’ fulfils that promise. However, late in his creative process, around the same time that he was interrupting himself to recall the African sailor of his Liverpool summer, Melville also revised both title and subtitle into something more personal and intimate than historical, something biographical: he changed the title to ‘Billy Budd, Sailor(An inside narrative.)’.

The original subtitle ‘What befell him’ (and its provocative ‘&c.’) suggests a sea narrative with unfortunate events but no announced prospect of psychological trauma: nothing to hint at Billy’s beauty and yet his flash-pan anger and stutter; nor Claggart’s envy and iniquitous deceit; nor Vere’s intellect and yet fatal detachment. As Melville added and revised one tragic figure after another, his narrator becomes less successful in his attempts to penetrate each mind. In Chapter 8 – also expanded around the time he revised ‘forecastle-magnate’ – Melville’s narrator tries to comprehend Claggart’s antipathy for Billy but admits: ‘His portrait I essay, but shall never hit it’ and later in Chapter 11, as he stumbles over the ‘mysteries’ of Claggart’s ‘iniquity’, he says he can explain the character only through ‘indirection’. In Chapter 21 – an even later expansion – the narrator compares the impossible task of drawing a line between sanity and insanity in Vere’s behaviour to the impossibility of delineating where ‘in the rainbow’ one colour ends and the next begins.

Melville’s beset narrator cannot get to the truths regarding these men’s variant masculinities; he can only get at them, around them, indirectly. His portraits are perpetually essayed and always incomplete. He can only insinuate how the three men are strangely undone: one by his beauty, another by self-loathing, the third by his insistence on ‘forms, measured forms’. Since the novella’s publication in 1924, readers have debated who is the tragic hero in this triple tragedy. That debate shall remain perpetually uncompleted largely because the narrative’s rhetorical structure was designed to embody an aesthetics of incompletion.

Sometime after the spring of 1889 and thinking, for the time being, that he was done with Billy Budd, Melville returned to the first page of his manuscript, and, in the upper left-hand corner, pencilled a new title and subtitle for his still-expanding novella. His new work would be ‘(An inside narrative.)’, with this subtitle formatted as you see it: beginning with a capital, ending with a period, and surrounded by parentheses (see Figure 6). No longer a factual report of what ‘befell’ Billy in a time before steamships, the new subtitle promises privileged access to an ‘inside’ hence frank and veracious disclosure regarding one sailor.

Source: Herman Melville Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS AM 188 [363]

The capitalisation, period, and parenthesis enhance Melville’s provocation. Without the idiosyncratic punctuation and with conventional formatting – that is, all words capitalised, no period, no parenthesis – the subtitle would merely identify a genre: just as, let’s say, ‘A Story of Wall Street’ marks ‘Bartleby’ as an urban office chronicle. More enticing, it might resemble the sensationalising subtitles of a lurid penny dreadful. But Melville’s unconventional pointing and parenthesis render something more like an ‘aside’ in a play, as if an actor on stage is muttering the three words – (An inside narrative.) – confidentially for the audience’s ears only.

In this case, Melville’s parenthetical is an intimate disclosure to readers and an implicit contract: If you read my narrative, I will give you the truth; not what is assumed or rumoured to be true by those ‘outside’ the events but the real facts from someone on the ‘inside’. And yet that contract is unfulfilled, for while Billy Budd addresses interior human problems, its principal mysteries are unresolved. Why is beautiful manly Billy so angry and easily unmanned; why his stutter? Why must Claggart destroy the beauty he loves? Why is rational, fearless, thoughtful Vere so thoughtless of common mercy? The novella leaves all questions hanging. In retrospect, Melville’s intimate aside is a provocation. Its promise of an ‘inside narrative’ is a false claim that sets readers up for insights that are undeliverable. It is a staged indirection delivering a story that is purposely incomplete.

This reading of Melville’s subtitle is reinforced by its revision history. A close inspection of the Billy Budd manuscript reveals that Melville added his parenthetical marks in a later revision as an afterthought, two strokes enacting his agenda of incompletion. They appear in a distinctly darker pencil than the hastily inscribed words they embrace. Notice that the right parenthesis is more precisely shaped than the left because it has been squeezed into the tight space between the word narrative and the bubble circling the previously added subtitle. The tight-fitting parentheses tell us that they were inserted after the bubble had been inscribed; they are a revision within a revision that shows Melville adding a layer of meaning to his already provocative subtitle.

Even as Melville was squeezing in his ironic parentheticals, he was also crafting three new concluding chapters, each a short vignette leading, one after the other, to the novella’s concluding poem. The first offers an element of closure with Vere’s death and last words – ‘Billy Budd, Billy Budd’ – but no insight into the dying captain’s meaning. The second is a false, propagandistic newspaper account of the affair that depicts Claggart as a model officer and martyred victim of a deceptive, mutinous Billy. The third relates how in the aftermath, sailors mythologised Billy as a common-man Christ and introduces a sailor poet and his poem, ‘(Billy in the Darbies)’, another parenthesised title. Taken together the chapters and poem are a montage of divergent points of view. Segmented and fragmentary, they refuse us any deeper understanding of the characters and events on board Billy’s ship and direct our attention to even remoter worlds external to the drama: a death scene on land, a newspaper, a dockyard full of spars taken as relics, Billy’s vision of his hammocked corpse sinking into ‘oozy weeds’. Together, the sequence of ‘outside’ mini-narratives wander off in different perspectives and genres fading away from Billy’s dramatic execution scene and attesting to the futility of attempting any ‘inside narrative’.

Melville, it would seem, had a thing for parentheses: they signal digression, incidental second thoughts, a sidebar, or intimate disclosure. The pair he put around ‘(Billy in the Darbies)’ to close his novella, mimic those embracing ‘(An inside narrative.)’ at the beginning. The poem’s title came to him adventitiously, as a second thought erupting out of revisions to the poem’s penultimate line. Initially, to describe Billy’s handcuffs, Melville landed on ‘this iron’, a routine but perhaps too obvious metonym. Dissatisfied with ‘iron’, he essayed two other pencilled options: first ‘shackles’ then sailor slang ‘darbies’. Since the beginning of his Billy Budd project, he had no title for the sailor poem that would conclude the prose narrative. Now, at the eleventh hour, this revision sequence gave him a title for the not-yet-titled poem. In the same pencil but at the top of the poem’s first leaf, Melville inscribed ‘(Billy in the Darbies)’ (see Figure 7). At some point, also in the same pencil, he then declared that his prose-and-poem novella was, if not complete then at an end; he wrote: ‘End of Book / April 19th 1891’. Five months later, Melville died.

Source: Herman Melville Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS AM 188 [363]

Editors have represented Melville’s parentheticals differently. Neither the Northwestern-Newberry (NN) Edition (Melville, 2017) nor their source text from Hayford and Sealts’s Genetic Edition (Melville, 1962) retains Melville’s parentheses in the poem. They do retain the provocative parentheses in the novella’s subtitle but remove the period; the NN version also capitalises each word ‘(An Inside Narrative)’, converting Melville’s carefully formatted aside into conventional subtitle formatting. More problematic, however, is that the 1962 and 2017 editions designate Melville’s inserted parentheses as part of the subtitle’s original inscription, not as a revision inserted within the initial insertion. In short, the revision text is lost in these editions.

Our interpretation of a literary work depends upon how the work is edited. Some will assert that Melville’s parenthetical is a minor detail that cannot or does not have an impact on our reading, but assertions are not arguments, and such dismissive claims cannot be tested unless the revision data is opened for close reading, interpretation, and debate. MEL’s 2019 fluid-text edition of Billy Budd makes Melville’s revision texts accessible. It displays both novella subtitle and poem title as they appear in the manuscript, with both coded as revisions, and each accompanied by explanatory revision narratives. Readers can see how Melville purposely added parentheses around his subtitle, as if the writer were whispering his indirection for our ears only. Readers can also see how Melville’s ironic parenthetical indirection came as a second thought in a sequence of revisions, and how, as a last-minute provocation, it is part of a pattern of rhetorical indirection that discloses an underlying aesthetics of incompletion.13

MEL’s editing tool TextLab enables editors to mark up the ‘revision sites’ of a fluid text and annotate them with ‘revision narratives’ that explain each step of a ‘revision sequence’. Differing revision narratives will tell the story differently because different editors will see the sequence differently. They will have their own ‘inside revision narratives’ and an editorial forum in which to debate their relative merits. Perhaps, in discussing Melville’s revision practices, they may articulate arguments connecting his opening parenthetical ‘inside’ and closing ‘darbies’ and discern the deeper relevance of this revision scenario to the reading of the novella. The larger aim of fluid-text editing is to familiarise crabbed, messy, indecipherable, otherwise alienating revision texts in manuscript by making them visible, accessible, trackable, and easily read, with the further aim that the use of revision texts will become normalised in the practice of literary and cultural studies and thereby establish a discourse field in which scholars, critics, and educational communities may essay their own theories about revision and creativity. Or, in the case of Billy Budd, one may craft a biography of Melville himself as a fluid text, replaying memories by adding an African to his definition of ‘handsome’, squeezing parentheses around words fore and aft, growing and changing and essaying the ‘ragged edges’ of his not-yet-finished text and self: drawing readers into his aesthetics of incompletion.

Source: PS 2384.M7 1851a, copy 2, Helen and Ruth Regenstein Collection of Rare Books, The Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago

It reads: ‘Henry Hubbard / From his old Shipmate / and watchmate / On board the good ship / Ackushnet / (Alas, wrecked at last / on the Nor’ West) / Herman Melville / March 23d 1853 / Pittsfield. –’

Source: PS 2384.M7 1851a, copy 2, Helen and Ruth Regenstein Collection of Rare Books, The Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago

It reads in full: ‘Pip – Backus his real name. I was / on the boat at the time he made / his leap over board – / Stubs, J. Hall / his name. / Hubbard’

Source: Herman Melville Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS AM 188 [363]

Melville’s deletion of ‘forecastle hero’ appears on the first line of leaf 8. Barely visible even in the magnified inset, and directly above ‘hero’, Melville pencilled the word ‘magnate’ as a suggested revision, then erased it when he deleted ‘forecastle hero’. Later, in inserting leaf 7 to precede leaf 8, Melville combined the deleted words to give ‘white forecastle-magnate’ (see Figure 4).

Source: Herman Melville Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS AM 188 [363]

Melville’s careful fair-copying of ‘white / forecastle-magnate’ in ink indicates his certainty, at the time of inscription, of the phrase. But he deleted it, first in pencil, and then in two ink strokes. At the same time, he added ‘handsome’ and ‘sailor’, either together or separately, in the space and margin to the right of ‘white’. The arrangement of deletions and insertions suggest at least two revision sequences as to whether Melville removed ‘white’ first or last in his process.

Source: https://melville.electroniclibrary.org/editions [accessed 25 March 2025]

In MEL’s editorial design for Billy Budd, reader’s click on marginal thumbnails to access side-by-side leaf images and their diplomatic transcriptions for highlighted revision sites in the reading text. The transcription emulates the positioning of Melville’s revision texts and enables readers to decipher his handwriting and obscured or incomplete inscriptions.

Source: Herman Melville Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS AM 188 [363]

Source: Herman Melville Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS AM 188 [363]